Using SVGs is relatively straight forward — until you want to mix DOM and vector interactions.

In this series of SVG articles, we’ve looked at what SVGs are, why you should consider them and how you can embed them in your web pages. We’ve also looked at basic drawing elements and how more complex paths work.

SVGs have their own coordinate system defined in a viewBox attribute. For example:

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 800 600"> This sets a width of 800 units and a height of 600 units starting at 0,0. These units are arbitrary measurements for drawing purposes, and it’s possible to use fractions of a unit. If you position this SVG in an 800 by 600 pixel area, each SVG unit should map directly to a screen pixel.

However, vector images can be scaled to any size — especially in a responsive design. Your SVG could be scaled down to 400 by 300 or even stretched beyond recognition in a 10 by 1000 space. Adding further elements to this SVG becomes more difficult if you want to place them according to the cursor location.

Note: see Sara Soueidan’s viewport, viewBox and preserveAspectRatio article for more information about SVG coordinates.

Avoid Coordinate Translation

Table of Contents

You may be able to avoid translating between coordinate systems entirely.

SVGs embedded in the HTML page (rather than an image or CSS background) become part of the DOM and can be manipulated in a similar way to other elements. For example, take a basic SVG with a single circle:

<svg id="mysvg" xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 800 600" preserveAspectRatio="xMidYMid meet"> <circle id="mycircle" cx="400" cy="300" r="50" /> <svg> You can apply CSS effects to this:

circle { stroke-width: 5; stroke: #f00; fill: #ff0; } circle:hover { stroke: #090; fill: #fff; } You can also attach event handlers to modify attributes:

const mycircle = document.getElementById('mycircle'); mycircle.addEventListener('click', (e) => { console.log('circle clicked - enlarging'); mycircle.setAttribute('r', 60); }); The following example adds thirty random circles to an SVG image, applies a hover effect in CSS, and uses JavaScript to increase the radius by ten units when a circle is clicked.

See the Pen SVG interaction by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

SVG to DOM Coordinate Translation

It may become necessary to overlay a DOM element on top of an SVG element — for example, a menu or information box on the active country shown on a world map. Presuming the SVG is embedded into the HTML, elements become part of the DOM, so the getBoundingClientRect() method can be used to extract the position and dimensions. (Open the console in the example above to reveal the clicked circle’s new attributes following a radius increase.)

Element.getBoundingClientRect() is supported in all browsers and returns an DOMrect object with the following properties in pixel dimensions:

.xand.left: x-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the left side of the element.right: x-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the right side of the element.yand.top: y-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the top side of the element.bottom: y-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the bottom side of the element.width: width of the element (not supported in IE8 and below but is identical to.rightminus.left).height: height of the element (not supported in IE8 and below but is identical to.bottomminus.top)

All coordinates are relative to the browser viewport and will therefore change as the page is scrolled. The absolute location on the page can be calculated by adding window.scrollX to .left and window.scrollY to .top.

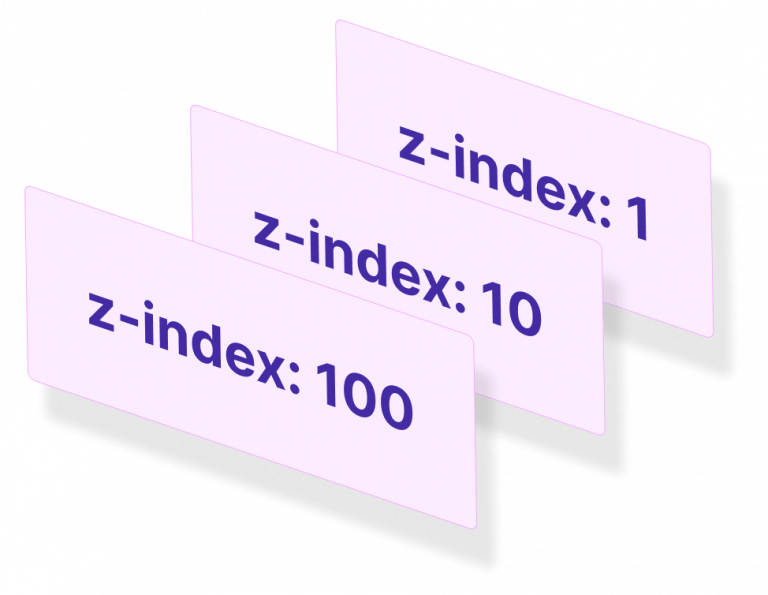

SVGs have their own coordinate system. It is defined via the viewbox attribute, e.g. viewbox="0 0 800 600" which sets a width of 800 units and a height of 600 units starting at (0, 0). If you position this SVG in an 800×600 pixel area, each SVG unit maps directly to a screen pixel.

However, the beauty of vector images is they can be scaled to any size. Your SVG could be scaled in a 400×300 space or even stretched beyond recognition in a 100×1200 space. Adding further elements to an SVG becomes difficult if you don’t know where to put them.

(SVG coordinate systems can be confusing – Sara Soueidan’s viewport, viewBox and preserveAspectRatio article describes the options.)

Simple Separated SVG Synergy

You may be able to avoid translating between coordinate systems entirely.

SVGs embedded in the page (rather than an image or CSS background) become part of the DOM and can be manipulated in a similar way to other elements. For example, given a basic SVG with a single circle:

[code language=”html”]

<svg id=”mysvg” xmlns=”http://www.w3.org/2000/svg” viewBox=”0 0 800 600″ preserveAspectRatio=”xMidYMid meet”>

<circle id=”mycircle” cx=”400″ cy=”300″ r=”50″ />

<svg>

[/code]

we can apply CSS effects:

[code language=”css”]

circle {

stroke-width: 5;

stroke: #f00;

fill: #ff0;

}

circle:hover {

stroke: #090;

fill: #fff;

}

[/code]

and attach event handlers to modify their attributes:

[code language=”javascript”]

var mycircle = document.getElementById(‘mycircle’);

mycircle.addEventListener(‘click’, function(e) {

console.log(‘circle clicked – enlarging’);

mycircle.setAttributeNS(null, ‘r’, 60);

}, false);

[/code]

The following example adds thirty random circles to an SVG image, applies a hover effect in CSS and uses JavaScript to increase the radius by ten units when a circle is clicked:

See the Pen SVG interaction by SitePoint (@SitePoint) on CodePen.

SVG to DOM Coordinate Translation

What if we want to overlay a DOM element on top of an SVG item, e.g. a menu or information box on a map? Again, because our HTML-embedded SVG elements form part of the DOM we can use the fabulous getBoundingClientRect() method to return all dimensions in a single call. Open the console in the example above to reveal the clicked circle’s new attributes following a radius increase.

Element.getBoundingClientRect() is supported in all browsers and returns an DOMrect object with the following properties in pixel dimensions:

.xand.left– x-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the left side of the element.right– x-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the right side of the element.yand.top– y-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the top side of the element.bottom– y-coordinate, relative to the viewport origin, of the bottom side of the element.width– width of the element (not supported in IE8 and below but is identical to.rightminus.left).height– height of the element (not supported in IE8 and below but is identical to.bottomminus.top)

Continue reading How to Translate from DOM to SVG Coordinates and Back Again on SitePoint.