Let’s talk about disabled buttons. Specifically, let’s get into why we use them and how we can do better than the traditional disabled attribute in HTML (e.g. <button disabled> ) to mark a button as disabled.

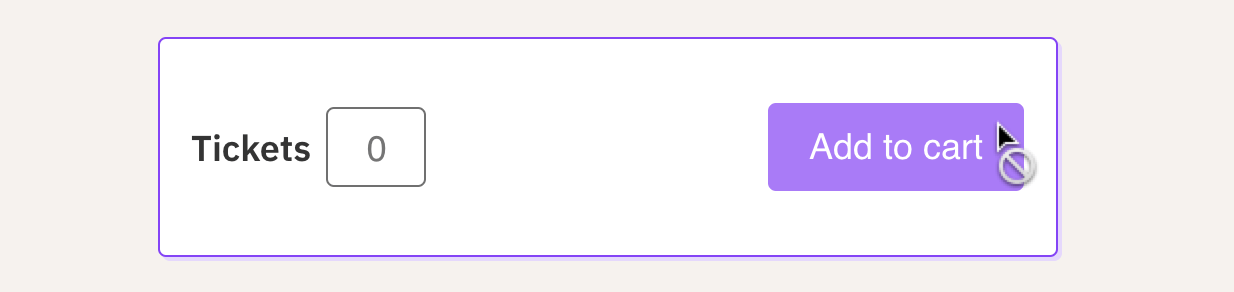

There are lots of use cases where a disabled button makes a lot of sense, and we’ll get to those reasons in just a moment. But throughout this article, we’ll be looking at a form that allows us to add a number of tickets to a shopping cart.

This is a good baseline example because there’s a clear situation for disabling the “Add to cart” button: when there are no tickets to add to the cart.

Table of Contents

Preventing people from doing an invalid or unavailable action is the most common reason we might reach for a disabled button. In the demo below, we can only add tickets if the number of tickets being added to the cart is greater than zero. Give it a try:

Allow me to skip the code explanation in this demo and focus our attention on what’s important: the “Add to cart” button.

<button type="submit" disabled="disabled"> Add to cart

</button>This button is disabled by the disabled attribute. (Note that this is a boolean attribute, which means that it can be written as disabled or disabled="disabled".)

Everything seems fine… so what’s wrong with it?

Well, to be honest, I could end the article right here asking you to not use disabled buttons because they suck, and instead use better patterns. But let’s be realistic: sometimes disabling a button is the solution that makes the most sense.

With that being said, for this demo purpose, we’ll pretend that disabling the “Add to cart” button is the best solution (spoiler alert: it’s not). We can still use it to learn how it works and improve its usability along the way.

Types of interactions

I’d like to clarify what I mean by disabled buttons being usable. You may think, If the button is disabled, it shouldn’t be usable, so… what’s the catch?

Bear with me.

On the web, there are multiple ways to interact with a page. Using a mouse is one of the most common, but there are others, like sighted people who use the keyboard to navigate because of a motor impairment.

Try to navigate the demo above using only the Tab key to go forward and Tab + Shift to go backward. You’ll notice how the disabled button is skipped. The focus goes directly from the ticket input to the “dummy terms” link.

Tab key, it changes the focus from the input to the link, skipping the “Add to cart” button.Let’s pause for a second and recap the reason that lead us to disable the button in the first place versus what we had actually accomplished.

It’s common to associate “interacting” with “clicking” but they are two different concepts. Yes, click is a type of interaction, but it’s only one among others, like hover and focus.

In other words…

All clicks are interactions, but not all interactions are clicks.

Our goal is to prevent the click, but by using disabled, we are preventing not only the click, but also the focus, which means we might be doing as much harm as good. Sure, this behavior might seem harmless, but it causes confusion. People with a cognitive disability may struggle to understand why they are unable to focus the button.

In the following demo, we tweaked the layout a little. If you use a mouse, and hover over the submit button, a tooltip is shown explaining why the button is disabled. That’s great! But if you use only the keyboard, there’s no way of seeing that tooltip because the button cannot be focused with disabled. Ouch!

Tab key.Allow me to once again skip past the code explanation. I highly recommend reading “Inclusive Tooltips” by Haydon Pickering and “Tooltips in the time of WCAG 2.1” by Sarah Higley to fully understand the tooltip pattern.

ARIA to the rescue

The disabled attribute in a <button> is doing more than necessary. This is one of the few cases I know of where a native HTML attribute can do more harm than good. Using an ARIA attribute can do a better job, allowing us to add not only focus on the button, but do so consistently to create an inclusive experience for more people and use cases.

The disabled attribute correlates to aria-disabled="true". Give the following demo a try, again, using only the keyboard. Notice how the button, although marked disabled, is still accessible by focus and triggers the tooltip!

Tab key, the “Add to cart” button is focused and it shows the tooltip.Cool, huh? Such tiny tweak for a big improvement!

But we’re not done quite yet. The caveat here is that we still need to prevent the click programmatically, using JavaScript.

elForm.addEventListener('submit', function (event) { event.preventDefault(); /* prevent native form submit */ const isDisabled = elButtonSubmit.getAttribute('aria-disabled') === 'true'; if (isDisabled || isSubmitting) { // return early to prevent the ticket from being added return; } isSubmitting = true; // ... code to add to cart... isSubmitting = false;

})You might be familiar with this pattern as a way to prevent double clicks from submitting a form twice. If you were using the disabled attribute for that reason, I’d prefer not to do it because that causes the temporary loss of the keyboard focus while the form is submitting.

The difference between disabled and aria-disabled

You might ask: if aria-disabled doesn’t prevent the click by default, what’s the point of using it? To answer that, we need to understand the difference between both attributes:

| Feature / Attribute | disabled |

aria-disabled="true" |

|---|---|---|

| Prevent click | ✅ | ❌ |

| Prevent hover | ❌ | ❌ |

| Prevent focus | ✅ | ❌ |

| Default CSS styles | ✅ | ❌ |

| Semantics | ✅ | ✅ |

The only overlap between the two is semantics. Both attributes will announce that the button is indeed disabled, and that’s a good thing.

Contrary to the disabled attribute, aria-disabled is all about semantics. ARIA attributes never change the application behavior or styles by default. Their only purpose is to help assistive technologies (e.g. screen readers) to announce the page content in a more meaningful and robust way.

So far, we’ve talked about two types of people, those who click and those who Tab. Now let’s talk about another type: those with visual impairments (e.g. blindness, low vision) who use screen readers to navigate the web.

People who use screen readers, often prefer to navigate form fields using the Tab key. Now look an how VoiceOver on macOS completely skips the disabled button.

Tab key.Once again, this is a very minimal form. In a longer one, looking for a submit button that isn’t there right away can be annoying. Imagine a form where the submit button is hidden and only visible when you completely fill out the form. That’s what some people feel like when the disabled attribute is used.

Fortunately, buttons with disabled are not totally unreachable by screen readers. You can still navigate each element individually, one by one, and eventually you’ll find the button.

Although possible, this is an annoying experience. On the other hand, with aria-disabled, the screen reader will focus the button normally and properly announce its status. Note that the announcement is slightly different between screen readers. For example, NVDA and JWAS say “button, unavailable” but VoiceOver says “button, dimmed.”

Tab key because of aria-disabled.I’ve mapped out how both attributes create different user experiences based on the tools we just used:

| Tool / Attribute | disabled |

aria-disabled="true" |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse or tap | Prevents a button click. | Requires JS to prevent the click. |

| Tab | Unable to focus the button. | Able to focus the button. |

| Screen reader | Button is difficult to locate. | Button is easily located. |

So, the main differences between both attributes are:

disabledmight skip the button when using theTabkey, leading to confusion.aria-disabledwill still focus the button and announce that it exists, but that it isn’t enabled yet; the same way you might perceive it visually.

This is the case where it’s important to acknowledge the subtle difference between accessibility and usability. Accessibility is a measure of someone being able to use something. Usability is a measure of how easy something is to use.

Given that, is disabled accessible? Yes. Does it have a good usability? I don’t think so.

Can we do better?

I wouldn’t feel good with myself if I finished this article without showing you the real inclusive solution for our ticket form example. Whenever possible, don’t use disabled buttons. Let people click it at any time and, if necessary, show an error message as feedback. This approach also solves other problems:

- Less cognitive friction: Allow people to submit the form at any time. This removes the uncertainty of whether the button is even disabled in the first place.

- Color contrast: Although a disabled button doesn’t need to meet the WCAG 1.4.3 color contrast, I believe we should guarantee that an element is always properly visible regardless of its state. But that’s something we don’t have to worry about now because the button isn’t disabled anymore.

Final thoughts

The disabled attribute in <button> is a peculiar case where, although highly known by the community, it might not be the best approach to solve a particular problem. Don’t get me wrong because I’m not saying disabled is always bad. There are still some cases where it still makes sense to use it (e.g. pagination).

To be honest, I don’t see the disabled attribute exactly as an accessibility issue. What concerns me is more of a usability issue. By swapping the disabled attribute with aria-disabled, we can make someone’s experience much more enjoyable.

This is yet one more step into my journey on web accessibility. Over the years, I’ve discovered that accessibility is much more than complying with web standards. Dealing with user experiences is tricky and most situations require making trade-offs and compromises in how we approach a solution. There’s no silver bullet for perfect accessibility.

Our duty as web creators is to look for and understand the different solutions that are available. Only then we can make the best possible choice. There’s no sense in pretending the problems don’t exist.

At the end of the day, remember that there’s nothing preventing you from making the web a more inclusive place.

Bonus

Still there? Let me mention two last things about this demo that I think are worthy:

1. Live Regions will announce dynamic content

In the demo, two parts of the content changed dynamically: the form submit button and the success confirmation (“Added [X] tickets!”).

These changes are visually perceived, however, for people with vision impairments using screen readers, that just ain’t the reality. To solve it, we need to turn those messages into Live Regions. Those allow assistive technologies to listen for changes and announce the updated messages when they happen.

There is a .sr-only class in the demo that hides a <span> containing a loading message, but allows it to be announced by screen readers. In this case, aria-live="assertive" is applied to the <span> and it holds a meaningful message after the form is submitting and is in the process of loading. This way, we can announce to the user that the form is working and to be patient as it loads. Additionally, we do the same to the form feedback element.

<button type="submit" aria-disabled="true"> Add to cart <span aria-live="assertive" class="sr-only js-loadingMsg"> <!-- Use JavaScript to inject the the loading message --> </span>

</button> <p aria-live="assertive" class="formStatus"> <!-- Use JavaScript to inject the success message -->

</p>Note that the aria-live attribute must be present in the DOM right from the beginning, even if the element doesn’t hold any message yet, otherwise, Assistive Technologies may not work properly.

There’s much more to tell you about this little aria-live attribute and the big things it does. There are gotchas as well. For example, if it is applied incorrectly, the attribute can do more harm than good. It’s worth reading “Using aria-live” by Ire Aderinokun and Adrian Roselli’s “Loading Skeletons” to better understand how it works and how to use it.

2. Do not use pointer-events to prevent the click

This is an alternative (and incorrect) implementation that I’ve seen around the web. This uses pointer-events: none; in CSS to prevent the click (without any HTML attribute). Please, do not do this. Here’s an ugly Pen that will hopefully demonstrate why. I repeat, do not do this.

Although that CSS does indeed prevent a mouse click, remember that it won’t prevent focus and keyboard navigation, which can lead to unexpected outcomes or, even worse, bugs.

In other words, using this CSS rule as a strategy to prevent a click, is pointless (get it?). 😉