Facebook and Instagram will give users the choice to hide “Like” counts on their own posts as well as others’ posts that appear in their feeds, the company announced on Wednesday.

The move comes after years of criticism that Facebook’s platforms — and particularly Instagram, which Facebook owns — fuel a pressurized and toxic social media environment that damages peoples’ mental health and body image. Instagram head Adam Mosseri said in a call with reporters that surveys showed the well-being of users didn’t change when “Like” counts were removed and that people didn’t use the app less or more. “I think we had a sense that we were going to lose users,” Mosseri explained. “It doesn’t look like we are going to.”

Users will now have a bit more control over when they see “Like” counts, but the new features do not represent a major change in how these social networks actually work. Instead, Facebook and Instagram are pushing the decision over how “Likes” are handled to users themselves, which amounts to another example of how Facebook tends to deflect responsibility for its platforms’ worst impulses and impacts onto users while making promises of more “choice.”

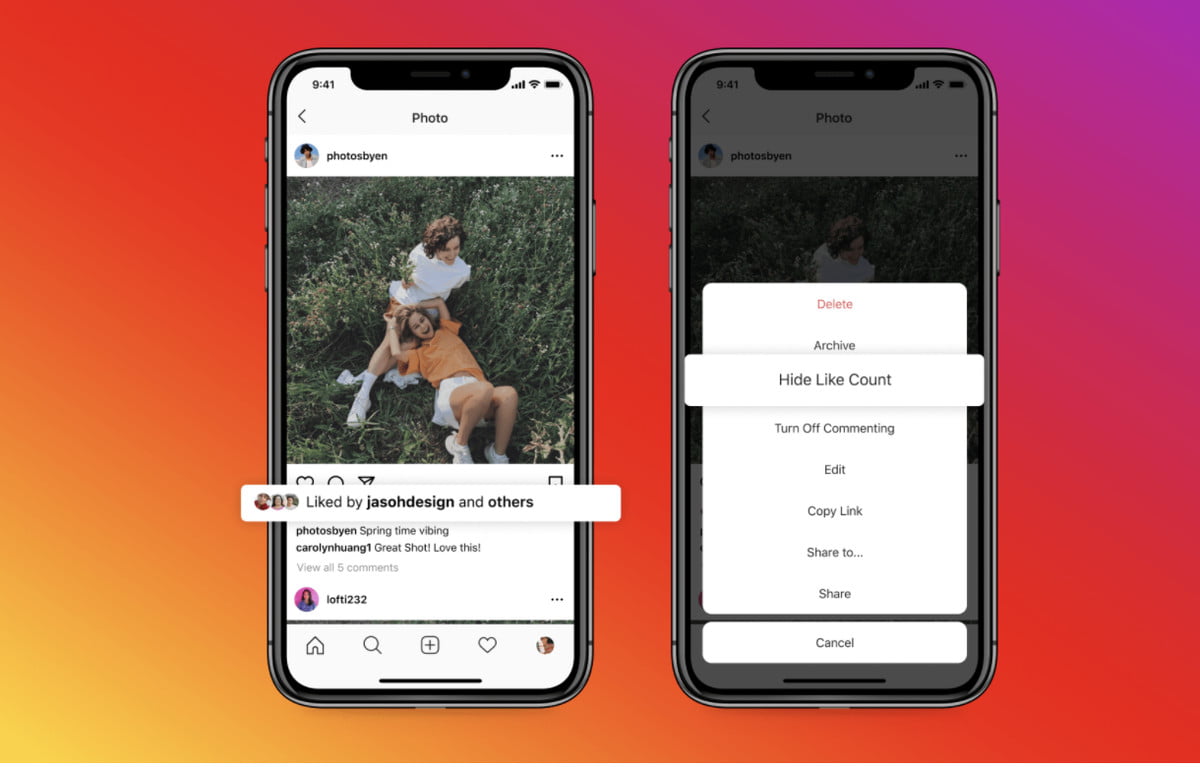

The new “Like” count feature is rolling out on Instagram and Facebook starting today. On Instagram, this means that users will now be able to go into the app’s settings and turn off “Like” counts on other peoples’ posts. To do this in the app, go to Settings —> Posts, where you’ll see a toggle that, when switched on, hides the “Like” counts viewable on posts from other people that show up in your feed. The default setting is that “Likes” are visible, so again, users will have to go into the app and proactively change the setting if they want to discontinue seeing “Likes.”.

Users can also ensure that other people can’t see the total number of “Likes” on their own posts. But that’s a little bit harder to do: It doesn’t appear that users can hide “Likes” on all their posts by default. Instead, they have to decide whether “Likes” should be visible for every single post and proactively turn them off.

It’s important to note that the underlying metrics that power Instagram aren’t changing. “Likes” and data generated by “Like”-based activity aren’t going away, and users will still be able to view how many “Likes” their own posts are getting, even if they’ve hidden those numbers from others. Other metrics on Instagram also remain visible to users, including Instagram story views, the number of comments on posts, and follower counts. Mosseri told reporters that leaving the “Like” count feature intact but making users decide whether or not to see it allowed the company to reconcile those who value “Like” counts with those who don’t.

“You might’ve seen that we’ve been testing different options for a while and this update reflects the feedback we’ve gotten,” Mosseri said in a tweet on Wednesday. “We want you to feel good about the time you spend on our apps and this is a way to give you more control over your experience.”

Notably, “Likes” can be a valued source of information for influencers and creators who use the platform regularly.

“I see this as a slick decision on the part of Facebook to put the onus of metric visibility on its users; it allows them to shore up what seems to be a superficial commitment to users’ mental health while allowing creators to continue to drive users — and hence data — to their platforms,” Brooke Erin Duffy, a professor of communications who has studied social media, told Recode in an email. Duffy added that Facebook’s decision to leave the choice up to individual users seems like an effort to appease creators and influencers, as well as “everyday users,” without changing Facebook’s core model.

wrote in 2019, “While generally put forth with positive intentions, these overdue measures ignore the fact that no matter how much Instagram would like to be viewed as a place users feel good about visiting, its entire existence is predicated on reminding people that other people are having more fun than they are.”

And despite calls for reforms, it’s not clear that major, fundamental changes to Facebook and Instagram are coming anytime soon. We should still expect these social networks to continue making incremental changes and adjustments to features, providing users with more options rather than more structural reforms of these platforms. History indicates that this is how Facebook is likely to approach problems.

In March, for example, Facebook published a somewhat wonky “Feed Filter” feature to allow users to decide for themselves whether they want to see an algorithmically curated or reverse-chronological News Feed, while also insisting that Facebook the company is not particularly responsible for political polarization and extreme content. Other new tools meant to give users a semblance of control include a “Favorites Feed,” which is meant to allow users to curate their own News Feeds, and a choose who can comment feature, which users are meant to take advantage of to “limit potentially unwanted interactions.”

None of these features are necessarily bad, but they contribute to the troubling trend: Facebook responds to its toughest structural issues by making small tweaks to the user experience or to specific settings. And then it’s up to users to tweak those settings and adjust how they use the platform with the hope that, somehow, the bad aspects of Facebook will just go away.