For the past several months, a fight has been brewing inside Apple, the world’s most profitable company, about a fundamental aspect of its business: whether its corporate employees must return to the office.

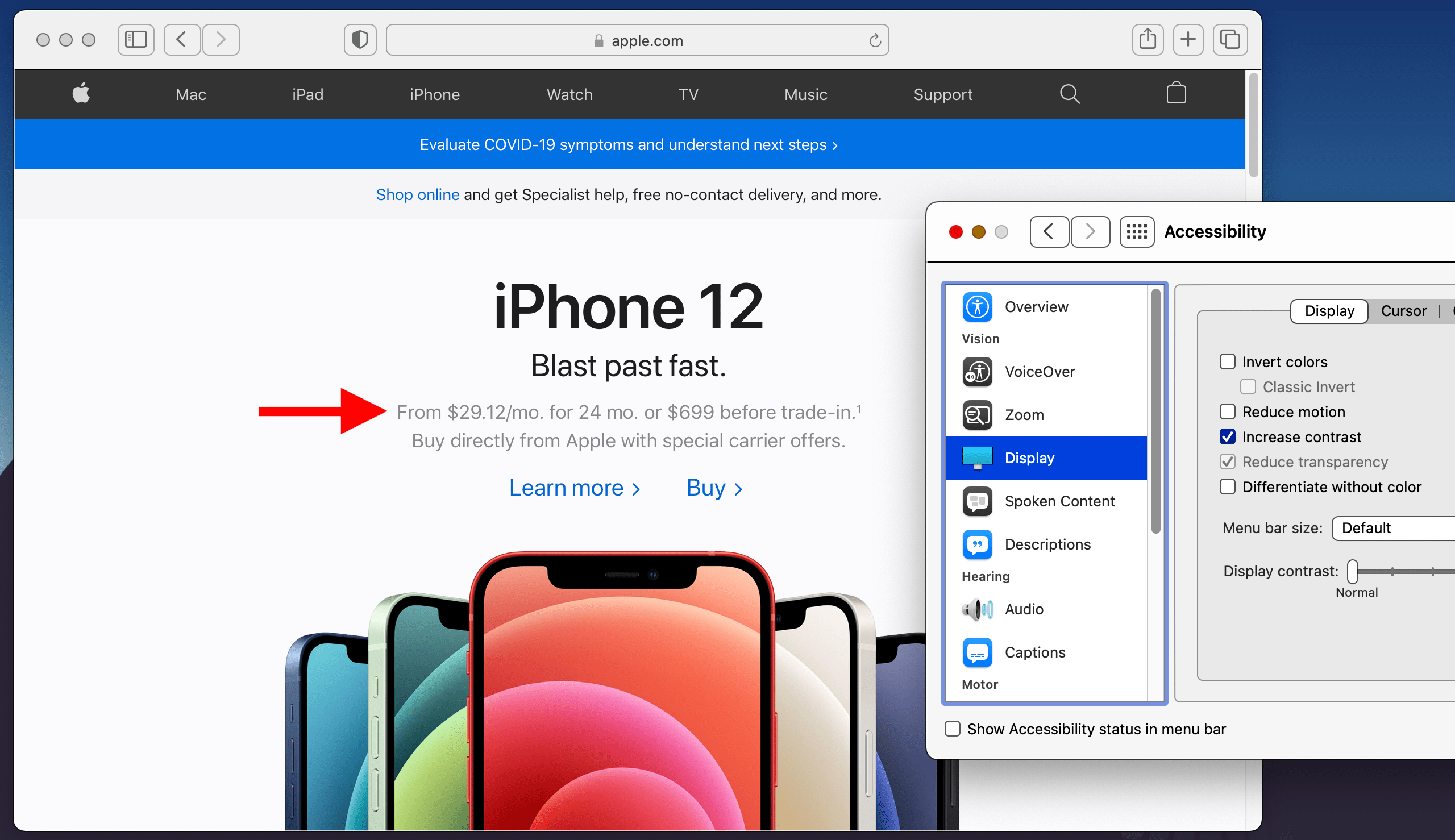

Apple expects employees to return to their desks at least three days a week when its offices reopen. And although the Covid-19 delta variant has made it unclear exactly when that will be, Apple’s normally heads-down employees are pushing back in an unprecedented way. They’ve created two petitions demanding the option to work remotely full time that have collected over 1,000 signatures combined, a handful of people have resigned over the matter, and some employees have begun speaking out publicly to criticize management’s stance.

Apple employees who don’t want to return to the office are challenging the popular management philosophy at many Silicon Valley companies that serendipitous, in-person collaboration is necessary to fuel innovation.

“There’s this idea that people skateboarding around tech campuses are bumping into each other and coming up with great new inventions,” said Cher Scarlett, an engineer at Apple who joined the company during the pandemic and has become a leader in, among other issues, organizing her colleagues on pushing for more remote work. “That’s just not true,” she said.

If Apple doesn’t budge on its remote work policy — and everything it’s said so far indicates that it won’t — some of its workers will likely jump ship. But Apple can afford to draw a hard line here because of its enormous power. The company offers workers hard-to-beat pay, benefits, and prestige, so it’s capable of retaining most of its workforce and continuing to attract top talent, regardless of its stance on flexible work.

Other companies will either copy Apple’s remote work policies and risk losing more workers than Apple would — or they’ll try to compete with the tech giant by offering something it won’t.

“This is a huge opportunity to essentially poach talent from companies that are just too rigid,” Art Zeile, CEO of Dice, a hiring platform for tech recruiters, said.

And those are just the potential consequences in the short term. This fight will have bigger ramifications later on. That this battle is happening at Apple signals a major shift for the company. For the most part, until now, it’s managed to avoid the internal conflicts that have seized other tech companies like Google. Now Apple will need to reckon with internal employee activists who are learning to pressure their employer about issues beyond remote work, like pay parity and gender discrimination. Even when the question of remote work is eventually settled, its employees are now emboldened to push for other demands — and so Apple will likely continue to grapple with this challenge.

Apple did not respond to a request for comment.

While the immediate outcome of this conflict will mainly affect Apple workers, its ripple effects will impact white-collar workers elsewhere, both in and outside of the tech world. That’s because the fight itself reveals a growing tension in corporate America over what the future of work should look like for knowledge workers. Does a successful, innovative company like Apple need its employees to show up in person? Or can it adapt to its workers and offer them more flexibility while expecting the same results? What Apple decides will likely influence a host of other companies that will either emulate its choice or react to it.

Inside the fight at Apple

Table of Contents

For Apple employees like Scarlett — a single mom with ADHD — working remotely has been a godsend. At home, she’s not distracted by coworkers’ conversations as she would be in an open office, and she can use some of the time she saves to pick up her daughter from school.

“Being a single mom, there wasn’t anybody to get my daughter or stay with her. Before, it would come up that I leave the office a lot to do that,” Scarlett told Recode. “Now, I no longer have that anxiety of feeling the need to explain that there is no one else to pick up my child.”

Scarlett is one of over 7,000 Apple employees who participate regularly in an internal corporate Slack group called “remote work advocacy,” where workers discuss their frustrations with management on the issue, and how other companies are offering more flexible arrangements. The group’s beginnings were relatively uncontroversial — it started as a place for Apple employees to share tips about how to work productively from home — but it turned into a hub of worker organizing.

The worker organizing in the group has also spilled over into public view — another rare phenomenon at the intensely private company — beginning with when The Verge first reported in early June that employees were petitioning Apple to continue working remotely. For a while, leaders of the petitions were hopeful that management might concede to some of their ideas, especially after HR met with organizers to hear out their concerns about returning to work.

But so far, management has ignored or dismissed employee demands, saying that the company needs its workers to show up.

“We believe that in-person collaboration is essential to our culture and our future,” said Deirdre O’Brien, Apple’s senior vice president of retail and people operations, in a video sent to staff in late June that The Verge obtained, a few weeks after the first petition was circulated.

In response, employees distributed a new internal petition, as Recode first reported, proposing more detailed plans for how employees could continue to work remotely full time.

And at a recent all-hands, which Recode obtained a recording of, CEO Tim Cook addressed some of the pushback on his return-to-office plan.

“I realize there are different opinions on it,” said Cook about Apple’s current plan to have employees come to work three days a week. “Some people would like to come in less, or not at all, some people would like to come in more.” While Cook didn’t concede to any employee demands, he did say the company is “committed to learning and tweaking.”

“We’ll see how that goes,” said Cook. After details of that meeting were published in the press, Cook sent a memo condemning employees who leak, saying that they “do not belong at Apple” — and that memo was then leaked to The Verge.

As the debate over remote work drags on, it’s added to other longstanding tensions at Apple around the company’s notoriously high-pressure culture — which employees are critiquing more candidly than before.

“We had a running joke where we had a ‘crying room’ at the office,” Parrish told Recode. “We are as a group happier, healthier, and just doing so much better than we ever were in the office. And that’s because we’re able to have our own spaces … we’re able to escape a little bit from some of the more toxic elements of work.”

Discussions about working from home have also been followed by more public discussions about other issues at the company, including pay disparity. Scarlett started a survey asking employees to self-report their salaries and demographic information, which was posted in the remote work advocacy channel and other channels.

That survey, first reported on by The Verge, ended up showing that out of the 2,400 people who responded, women earned about 6 percent less on average than men. The self-run study doesn’t necessarily represent a full picture of Apple’s workforce — respondents opted in and thus were a self-selecting group. But it did further suspicions among some employees that the company may not pay all men and women equally (which it has said it has done since 2016).

All this employee backlash at Apple over remote work is a testament to how important the issue is for knowledge workers across industries. For many, remote work during the pandemic made their lives better. Skipping a commute or being able to duck out in the middle of the day to run errands or shepherd children gave people a better sense of work-life balance. For those who felt left out from office camaraderie and extracurricular activities, the ability to work from home has been less isolating.

Recode spoke with a handful of other Apple employees who shared why they and some of their colleagues don’t want to return to the office. Their perspectives mirror that of many other white-collar workers, particularly those who used to work at corporate campuses in expensive urban areas like San Francisco, Seattle, and New York. One thing some cited, in addition to family and medical reasons, was the incredibly high cost of housing near Apple’s headquarters in Silicon Valley. For the first time, some workers were able to move farther away from the office to more affordable areas on the outskirts. For those who currently have no commute, it’s hard to imagine going back to driving a two- to four-hour round trip.

Parrish said that she is often on calls as early as 6 am and sometimes as late as 10:30 pm. She finds it much easier to take those calls from home.

“For a lot of people, remote work allowed them a kind of work-life balance that was absolutely impossible in the office,” said Parrish, who said she also has health concerns about returning to the office because her partner is immunocompromised. “I’m able to have a life outside my job again, and I’m not willing to give that up.”

Parrish isn’t alone, and her concerns aren’t unique to Apple. Workers of all kinds — regardless of whether their job or industry is suitable to it — overwhelmingly want the ability to work from home, at least some of the time, according to data from Boston Consulting Group. For the remote jobs on its platforms, LinkedIn says it sees two and a half times more applications than it does for non-remote jobs.

Meanwhile, US employers are desperately in need of workers of all types to fill millions of jobs, both white collar and blue collar. But workers, for a variety of reasons, aren’t taking those jobs, as many of them hold out for better options — especially ones that offer remote work. White-collar workers, particularly tech workers, are much more likely to get this kind of work since their jobs are more easily done at home and since their skills are considered less replaceable than those of their blue-collar counterparts. Nearly half of jobs on the tech job platform Hired now allow full-time remote, while remote job listings on a more general job site, LinkedIn, are at 16 percent.

While it’s unlikely that Apple’s retail employees will be able to work from home, the fact that they are continuing to communicate and organize with corporate staff may be a sign of broader worker activism Apple will have to confront in its future.

Why Apple is fighting remote work

One of the most critical reasons Apple is fighting to get people back in the office is that its leaders think being in the office is good for business.

“Innovation isn’t always a planned activity,” Cook told People magazine this spring. “It’s bumping into each other over the course of the day and advancing an idea that you just had. And you really need to be together to do that.”

“I don’t think [management] is entirely wrong,” one Apple engineer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of Apple’s policy against employees speaking to the press without authorization, told Recode. “I think there are hallway conversations that I miss. But I think they overstate the value of it.”

There isn’t hard evidence that spontaneous in-person meetings in the office, like what Cook describes, boost innovation for a company. But generally, having more connections with coworkers outside your team correlates to higher performance and creativity, according to research cited by Brandy Aven, an associate professor of organizational theory at Carnegie Mellon University. And you’re likely to bump into people outside your team if they’re physically nearby, so maybe Cook is onto something.

At many offices, particularly at a giant tech campus like Apple’s headquarters, there’s a sort of formula for encouraging workers to talk to each other, even if they don’t work in the same department or on the same project. Through architecture and design, which Apple has invested in heavily, management can channel workers into the same space with communal kitchens, centrally located bathrooms, and atriums.

That’s harder to recreate in the virtual world of Zoom calls, Slack, and email.

Aven, however, thinks companies could use technology to come up with creative solutions and replacements for this situation rather than relying on requiring workers to be present in the office.

“I think we could engineer serendipitous encounters over the web. Organizations just have to update and be a little bit more innovative,” Aven told Recode. “If we can put men in space, we can figure this problem out.”

For now, despite a year and a half forced experiment of working from home, we don’t know how remote work will affect things like innovation and collaboration in the long term. Companies are still trying to quantify the full impacts of remote work and trying different approaches to make it better. It’s an ongoing challenge, and how Apple responds — either by trying to bring its creativity to bear on remote work or by rejecting it outright — could have lasting influence on what remote work ends up looking like for everyone else.

One thing that sets Apple apart is that unlike other Silicon Valley giants such as Google and Facebook, it is primarily a hardware — not a software — company. That means it needs to test, tinker, and develop physical products in person.

The company’s success also depends, in part, on how tightly it can keep from its competition its plans to develop the latest iPhone or yet-to-be-announced gadget. If engineers and other staff working on sensitive products are allowed to do so at home, the thinking is, it may be easier for competitors to get access to confidential information.

For all these reasons, Apple management is holding its ground. But due to the delta variant, the company’s return-to-office plan has been put on pause. Apple pushed back its office reopening until at least January due to health concerns. The announcement came only a day after the second employee petition on the matter.

Several organizers Recode spoke with said they had no evidence that the petitions influenced Apple’s decision — but for now, the delta variant has essentially kicked the can down the road.

The ripple effects of Apple’s hard line on remote work

Even if everyone who signed the petitions at Apple were to quit, they would represent less than 1 percent of its workforce. In the short term, Apple will continue to be just fine regardless of what it decides about remote work.

“Apple is probably an aberration since they’re the largest company by market cap and they have such a great tradition of innovation, and you can’t go wrong with a career at Apple,” Dice CEO Zeile said. “But there are thousands of other companies that are still going to be rigid, potentially, in their hiring practices. They’re the ones that are going to lose.”

In other words, companies that aren’t like Apple will face more challenges if they choose to emulate the tech giant’s remote work policies.

“There’s an absolute war on for talent in tech,” Julia Pollak, a labor economist at ZipRecruiter, told Recode. She says there have been very few software engineer applications per vacancy. “Where companies have said, ‘We want you back in the office,’ or, ‘We want you in the office three days a week,’ it looks as though all of those positions are softening pretty quickly. And they’re being pushed into a corner by competitors, who are saying, ‘Hey, we don’t care if you’re fully remote all day long and working out of Hawaii.’”

Some other companies may choose to react strategically, rather than following suit, if Apple continues to reject employees’ calls for full-time remote work. That would create an opening for them to offer remote work to punch above their weight and attract more applicants.

And Twitter, which announced in May 2020 that its employees could work from anywhere forever, is already using remote work to poach talent from tech companies that are more strict about when and where people can work.

“We definitely think it gives us a competitive advantage,” Jennifer Christie, Twitter’s head of HR, told Recode. The company, she says, is telling prospective employees, “‘If you don’t want to wait and see what happens with your company’s work-from-home policy, come work for us.’ It’s a selling point for people who don’t want to be in limbo.”

In the near future, most of Apple’s employees seem like they’re willing to accept being in limbo. No matter what Apple decides, it can afford to take a hard line against employees pushing for full-time remote work. But in the long term, this battle over flexible work has created an opening for other issues and tensions to rise to the surface at the company. Its workers are organizing in ways they haven’t before, and they’re standing up to management in mostly unprecedented ways. That’s a challenge that Apple may need to deal with long after the debate over working from home is settled.