This story is part of a Recode series about Big Tech and antitrust. Over the next few weeks, we’ll cover what’s happening with Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft.

We love our mobile apps. It’s hard to think of something that at least one of the nearly 12 million apps out there can’t do. Order a taxi, buy clothes, get directions, play games, message friends, store vaccine cards, control hearing aids, eat, pray, love … the list goes on. You might be using an app to read this very article. And if you’re reading it on an iPhone, then you got that app through the App Store, the Apple-owned and -operated gateway for apps on its phones. But a lot of people want that to change.

Apple is facing growing scrutiny for the tight control it has over so much of the mobile-first, app-centric world it created. The iPhone, which was released in 2007, and the App Store, which came along a year later, helped make Apple one of the most valuable companies on the planet, as well as one of the most powerful. Now, lawmakers, regulators, developers, and consumers are questioning the extent and effects of that power — including if and how it should be reined in.

Efforts in the United States and abroad could significantly loosen Apple’s grip over one of its most important lines of business and fundamentally change how iPhone and iPad users get and pay for their apps. It could make many more apps available. It could make them less safe. And it could make them cheaper.

The iPhone maker isn’t the only company under the antitrust microscope. Once lauded as shining beacons of innovation and ingenuity that would guide the world into the 21st century, Apple is just one of several Big Tech companies now accused of amassing too much power over parts of the economy that have become as essential as steel, oil, and the telephone were in centuries past.

These companies have a great deal of control over what we can do on our phones, the items we buy online and how they get to our homes, our personal data, the internet ecosystem, even our online identities. Some believe the best way to deal with Big Tech now is the way we dealt with steel, oil, and telephone monopolies decades ago: by using antitrust laws to place restrictions on them or even break them up. And if our existing laws can’t do it, legislators want to introduce new laws that target the digital marketplace.

In her book Monopolies Suck, antitrust expert Sally Hubbard described Apple as a “warm and fuzzy monopolist” when compared to Facebook, Google, and Amazon, the other three companies in the so-called Big Four that have been accused of being too big. It doesn’t quite have the negative public perception that its three peers have, and the effects of its exclusive control over mobile apps on its consumers aren’t as obvious.

For many people, Facebook, Google, and Amazon are unavoidable realities of life on the internet these days, while Apple makes products they choose to buy. But more than half of the smartphones in the United States are iPhones, and as those phones become integrated into more facets of our daily lives, Apple’s exclusive control over what we can do with those phones and which apps we can use becomes more problematic. It’s also an outlier; rival mobile operating system Android allows pretty much any app, though app stores may have their own restrictions.

Apple makes the phones. But should Apple set the rules over everything we can do with them? And what are iPhone users missing out on when one company controls so much of their experience on them?

Apple’s vertical integration model was fine until it wasn’t

Table of Contents

Many of the problems Apple faces now come from a principle of its business model: Maintain as much control as possible over as many aspects of its products as possible. This is unusual for a computer manufacturer. You can buy a computer with a Microsoft operating system from a variety of manufacturers, and nearly 1,300 brands sell devices with Google’s Android operating system. But Apple’s operating systems — macOS, iOS, iPadOS, and watchOS — are only on Apple’s devices. Apple has said it does this to ensure that its products are easy to use, private, and secure. It’s a selling point for the company and a reason some customers are willing to pay a premium for Apple devices.

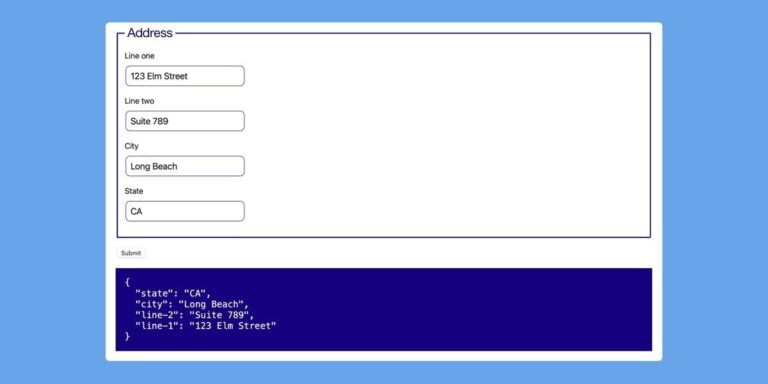

Apple doubled down on that vertical integration strategy when it came to mobile apps, only allowing customers to get them through the App Store it owns and operates. Outside developers have to follow Apple’s approval process and abide by its rules to get into the App Store. Apple has a lot of content restrictions for apps that the company says are intended to keep users safe from, for instance, “upsetting or offensive content.” Apple says in its developer guidelines, “If you’re looking to shock and offend people, the App Store isn’t the right place for your app.” But that means Apple mobile devices — more than 1 billion of them worldwide — aren’t the right place for your app, either.

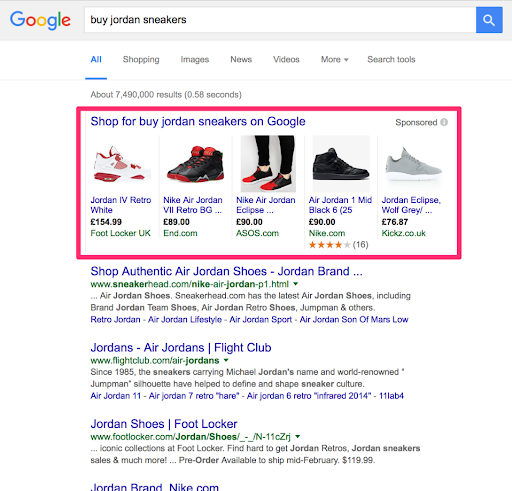

Developers whose apps do make it into the App Store may also find themselves paying Apple a hefty chunk of their income. Apple takes a commission from purchases of the apps themselves as well as purchases made within the apps. That commission is up to 30 percent and has been dubbed the App Store tax. There’s no way for apps to get around the commission for app purchases, and users have to pay for goods and services outside of the app to get around the in-app payment system’s commission.

Some of those developers are also competing with Apple when it comes to making certain kinds of apps. Developers have accused Apple of “Sherlocking” their apps — that’s when Apple makes an app that’s strikingly similar to a successful third-party app and promotes it in the App Store or integrates it into device software in ways that outside developers can’t. One famous example of this is how, after countless flashlight apps that used the iPhone’s camera flash became popular in the App Store, Apple built its own flashlight tool and integrated it into iOS in 2013. Suddenly, those third-party apps weren’t necessary.

Apple has also been accused of abusing its control to give it an advantage over streaming services. Spotify has complained for years that Apple has given an unfair competitive advantage to its Apple Music service, which came along a few years after Spotify. After all, Apple doesn’t have to pay an App Store tax for its own Music app, which comes pre-installed on iPhones and iPads, or the streaming service, which Apple can and does promote on its devices. (Apple points out that it only has 60 of its own apps, so clearly it’s not competing with every single third-party app in its store, or even the vast majority of them.)

“What Apple realized is that if they could control the App Store, they really control the rest of the game,” Daniel Hanley, senior legal analyst at Open Markets Institute, an anti-monopoly advocacy group, told Recode. “They don’t just control the hardware, now they control the software. They control how apps get on — it’s unilateral.”

This has all been a big moneymaker for Apple. Apple won’t say how big, but an expert said he believes the App Store alone made $22 billion in 2020, about 80 percent of which was profit. That profit margin estimate suggests that the mandatory commissions Apple takes from those apps far exceed the company’s costs for maintaining the App Store.

Because Apple refuses to allow alternate app stores or in-app payment systems, there’s no competition that might motivate it to lower those commissions — which could, in turn, allow developers to charge less for apps and in-app purchases. The House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust’s report from the Democratic majority cited numerous examples of developers claiming that they had to raise their own prices to consumers to compensate for Apple’s commission.

Apple disputes some of these numbers but, again, refuses to give its own. Its financial statements lump the App Store in with other “services,” including iCloud and Apple’s TV, Music, and Pay. Even so, there’s little doubt that the App Store’s success has helped, if not driven, Apple’s transition from being primarily a hardware company to a goods and services provider.

“It’s a nice, fat [revenue] stream where they don’t have to do a ton of R&D,” Brian Merchant, technology journalist and author of The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone, told Recode. “All they have to do is protect their walled garden.”

The case for only one App Store (Apple’s)

Apple says the security and privacy features its customers expect are impossible to provide without having this control over the apps on its phone. The company calls this a “trusted ecosystem.”

Craig Federighi, Apple’s senior vice president of software engineering, recently said that allowing Apple users to get apps through third-party app stores or by downloading them directly from the open internet (a practice known as sideloading) would open them up to a “Pandora’s box” of malware, though iPhones aren’t exactly immune to spyware. Similarly, Apple says its in-app payment systems are secure and private, which it can’t guarantee of anyone else’s.

These arguments aren’t necessarily wrong — there are plenty of malicious apps out there — but they don’t account for the fact that Apple doesn’t seem to have any problem with its Mac computers getting their apps from third-party app stores or through sideloading.

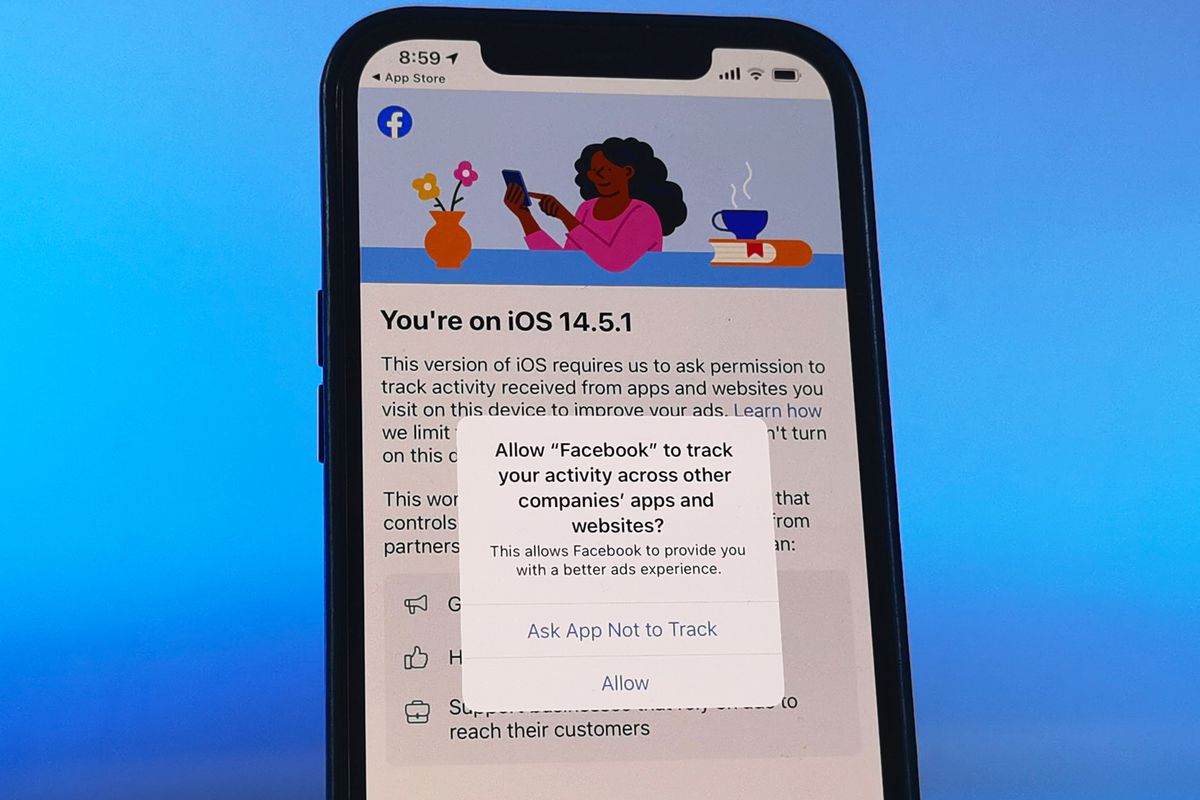

As for those commissions, Apple is quick to point out that the vast majority of apps, which are free, don’t pay Apple anything at all and still get all of the App Store’s benefits. Many apps are funded by selling ads and user data, which they don’t have to share with Apple, though Apple has recently tried to make this outside revenue stream less lucrative for developers by introducing anti-tracking features into iOS.

Those measures, which Apple says are designed to improve user privacy, could ultimately force developers to charge users for apps (more money for Apple!). So when Apple decided to stop much of that data flow, it upended an entire ecosystem worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year — Facebook was even reportedly considering filing an antitrust lawsuit over it. That’s how much control Apple has over its devices and, by extension, a considerable part of the global economy.

The App Store tax is also in line with what other app stores charge, per an independent report that Apple commissioned last year. Apple, the app store pioneer, was the one that set that 30 percent app store commission rate in the first place.

And Apple does allow for ways to get around some of its App Store taxes. People can purchase subscriptions and certain in-app services outside of apps if they have an account with the developer, which means no App Store tax to either raise prices or cut into the developer’s profit margin. Going to the developer’s website to pay also takes several more steps and more time on the part of the customer to do it.

But in the US, Apple’s best defense against accusations that its App Store is an illegal monopoly may be to simply point to existing antitrust laws, or at least how courts interpret them. Apple does have a monopoly on app stores on Apple devices, but there’s nothing necessarily illegal about that. Monopolies are only illegal if they operate in anti-competitive ways, and the bar to proving even that is pretty high. For the last four decades, courts have interpreted the law as protecting competition (and, by extension, the consumers who supposedly benefit from it), not competitors.

“Our law is very, very conservative,” Eleanor M. Fox, a professor of antitrust law and competition policy at New York University, told Recode. “Companies — even monopoly companies — do not have a duty to deal, and they don’t have a duty to deal fairly.”

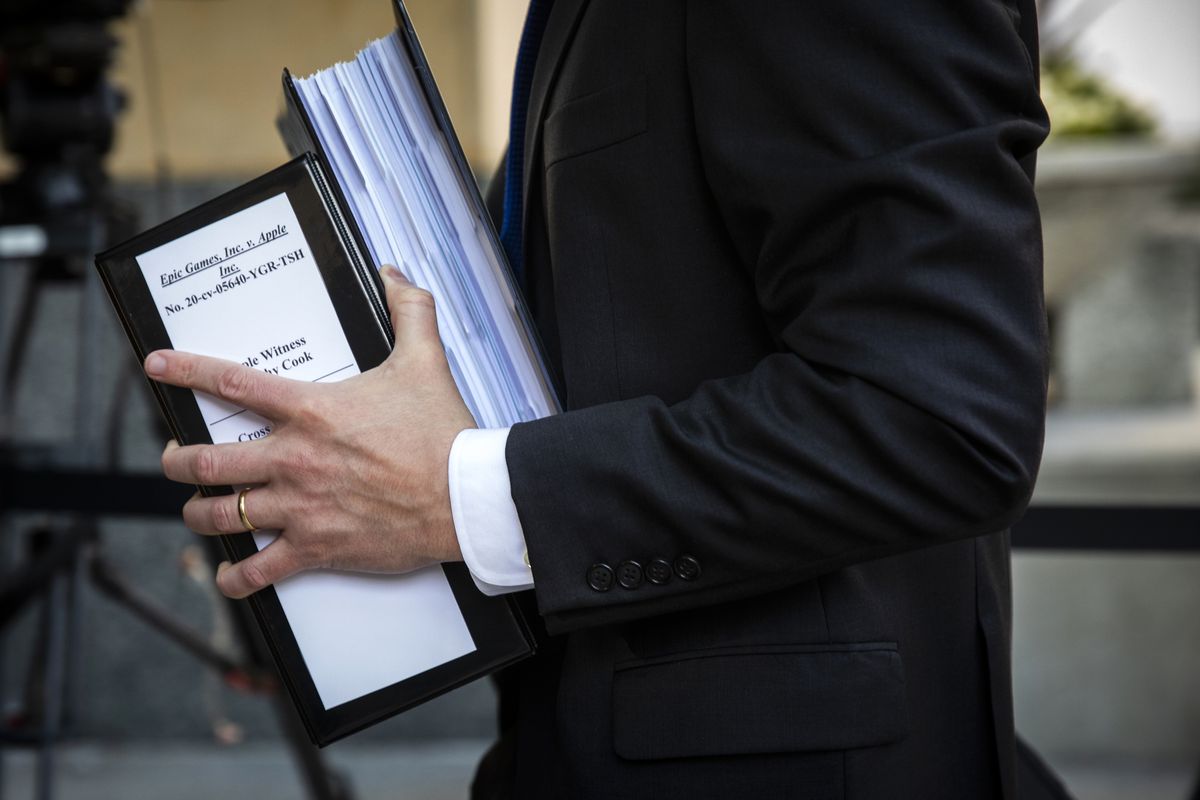

We’ve seen this precedent at work in the Epic Games v. Apple case. In August 2020, Epic Games, the developer behind the popular game Fortnite, sued Apple over its refusal to allow alternate app stores and payment systems, as well as its anti-steering policy that forbids developers from linking out to alternate ways to pay for app services or even telling users that other payment methods are possible. Apple kicked Fortnite out of its App Store when Epic tried to flout its rules. A federal judge ruled in September that Apple was well within its rights to do so.

The judge noted that the App Store had “procompetitive justifications.” Even though she found that Apple had a large part of the mobile gaming transactions market and that the App Store’s profit margins were “extraordinarily high,” she didn’t think it created a barrier to entry for developers, nor that it was harming innovation. (Epic has appealed this ruling.)

“Success is not illegal,” the judge wrote.

Epic’s only victory was that the judge ordered Apple to allow developers to link out to and inform users about other ways to pay for app services. Apple was able to delay that particular ruling, and according to a court filing, the company may even try to charge commissions on purchases made through the alternate payment systems if it’s forced to let developers link out to them. Even when Apple loses, it tries to find a way to win.

Apple’s attempts to avoid antitrust actions

While Apple insists that it isn’t doing anything wrong, the company appears to be concerned that its control over its devices faces some real threats. Apple historically refuses to give up ground on just about everything, yet it’s already made notable adjustments to some of its more controversial policies that could make some apps or services cheaper, or at least easier for the user to find cheaper ways to pay for them. Some of these changes were mandatory, yes, but others appear to be an effort to ward off harsher regulations or judgments.

For instance, Apple loosened its notoriously tight grip on repairs to its devices, allowing more independent shops and, very recently, individual consumers, to have access to the parts and instructions necessary to make certain fixes. This comes in the midst of a push for “right to repair” laws and pressure from the Biden administration and the Federal Trade Commission. But Apple still requires that its own parts be used for these repairs and sets the prices for them.

The stickiness and required usage of Apple’s native apps has long been a gripe from many iPhone users and a bad look for the company from an antitrust perspective. So this year, Apple started allowing users to select their own default apps for web browsing and mail; previously, Apple’s Safari and Mail apps were the mandatory default. Users have been able to delete most of the Apple apps that come pre-installed on their phones since 2018.

Apple has also given some developers a break on the App Store tax and anti-steering policies, which could reduce prices for consumers. Developers who make less than $1 million a year now only have to pay a 15 percent App Store tax. This came about as part of a settlement of a class action lawsuit, but Apple has presented it as a “Small Business Program” that’s “designed to accelerate innovation” (a phrase that could be read as implying that the 30 percent commission decelerated innovation).

Apple is also going to let developers contact customers outside of the app to let them know about alternate payment methods. As part of an agreement with the Japan Fair Trade Commission, Apple will soon let “reader” apps (that is, apps like Netflix and Spotify that offer media for purchase or subscription) link out to their own websites to make it easier for users to purchase subscriptions outside of Apple’s in-app payment system.

In 2016, Apple also cut its commission to 15 percent for subscription apps after the first year. Of course, this change was revealed at the same time as Apple’s announcement that it would sell search ads in its App Store, giving itself yet another exclusive source of revenue (and giving users a bunch of ads when they search the App Store).

But these concessions do nothing for the source of the vast majority of the App Store’s commissions: games from developers that make more than $1 million a year. And Apple hasn’t wavered on the practices that have drawn the bulk of the accusations that Apple’s practices — including the company not allowing alternate App Stores or sideloading, and not allowing alternate payment systems — are anti-competitive, increase prices for consumers, and reduce their choice. It seems unlikely that Apple will give way any time soon. Unless, of course, it has to.

How does Apple’s walled garden grow — or die?

There are plenty of reasons why Apple might have to change its ways. The company may have won most of the Epic Games lawsuit (pending Epic’s appeal), but it still faces antitrust action on several fronts that will play out over the coming years.

A growing number of countries have introduced or proposed laws that specifically target certain App Store practices, or are investigating Apple for potential violations of their competition rules. These include but are not limited to the European Union, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

Those could result in fines, which Apple, a $2 trillion company, probably isn’t too worried about. It also wouldn’t be the first time Apple has paid a considerable sum over antitrust violations. Another outcome — one that would be a much more troubling prospect for Apple — would be if the company were forced to change its business practices in order to keep operating in those countries.

But in the United States, courts haven’t seemed too bothered by Apple’s App Store rules. A federal judge recently threw out a class action lawsuit from developers that said Apple was abusing its monopoly power by refusing to allow their apps in the App Store. As the Epic Games ruling indicates, American antitrust laws (and most courts’ interpretation of them) haven’t done much to change or force change on Big Tech companies. If you’re a lawmaker who is concerned about Big Tech’s considerable power, that’s a green light to propose laws that will.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), for example, said the ruling showed that “much more must be done” about the “serious competition concerns” app stores raise. As chair of the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, as well as a member of the Commerce Committee, she’s in a pretty good position to push through bills that do just that.

Klobuchar is a co-sponsor of the Open App Markets Act, a bipartisan, bicameral bill that would do most of what Epic Games wanted. The legislation would force Apple to allow third-party app stores and the sideloading of third-party apps, require that app stores allow alternate payment systems, and forbid anti-steering policies. It would also ban app stores from giving their own apps special treatment or using non-public data from third-party apps to develop their own, competing apps.

The Open App Markets Act isn’t the only bill that could drastically change how Apple runs its App Store. Several more are currently making their way through both houses of Congress as part of its package of antitrust bills that target Big Tech. If passed, they’d also force Apple to include other app stores on its devices and forbid it from giving its own apps special treatment. One bill, the Ending Platform Monopolies Act, would even force Apple to break up its App Store and app development units into separate businesses.

All of these bills are bipartisan, but it’s far from certain that any of them will become law. If they do, and in something close to their current form, they could benefit consumers by giving them more choice of apps on their phone, and it could make those apps cheaper. It may also subject iPhone users to additional safety and security threats, as Apple alleges, while prices stay largely unchanged.

Apple says it supports updates to laws and regulations that benefit consumers, like privacy legislation — which the current bills on the table don’t do much to directly address.

The Department of Justice, which has been investigating Apple since 2019, is reportedly preparing a lawsuit concerning the App Store. It and the FTC enforce America’s antitrust laws. Both agencies are headed up by people who have accused Apple of anti-competitive actions or worked for firms that have. Lina Khan, a Big Tech critic who helped write the House’s report, is now the chair of the FTC, and Jonathan Kanter, who advised Spotify when it lobbied Congress to take action against Apple, leads the DOJ’s antitrust division. Both agencies may get a major, needed funding boost if the Build Back Better Act and a bill that increases merger fees for large companies pass.

With all of this said, Apple, “the warm and fuzzy monopolist,” is probably in a better position with its ongoing antitrust problems than its fellow Big Tech titans are with theirs. It has, so far, faced relatively less criticism in general, and many of the proposed bills and regulations don’t threaten its business model as much as they do that of the other companies. If Apple were forced to allow other app stores on its devices tomorrow, it would still have plenty of very healthy revenue streams.

Those may still include the App Store. It’s not clear that many of Apple’s users would even use or want another app store. The fact that they use an iPhone and not an Android speaks to this. They could prefer or trust the security and privacy protections in the App Store over those of, say, a Facebook app store. Then again, if those other app stores took a lower commission from developers, allowing them to charge less than the Apple App Store does, Apple’s customers may well vote with their wallets, and developers might only offer their apps in stores that give them a better margin. In which case, Apple might just find itself finally having to compete for apps and customers — and maybe even lowering the App Store tax to do it.

Apple wouldn’t be thrilled, but it would be just fine.

Update, December 9, 3:50 pm ET: This article has been updated to reflect that Apple won its appeal to delay implementing the court order to allow apps to link out to other payment methods.