Here is the straight news headline: Square, the financial services company run by Twitter co-founder and CEO Jack Dorsey, is buying Tidal, the streaming music service founded by Jay-Z.

And here is the question you, a normal person, may have about this deal: WTF?

The answer, depending on how you’re inclined to look at deals between billionaires, could be intriguing, silly, or stupid. Maybe all of the above.

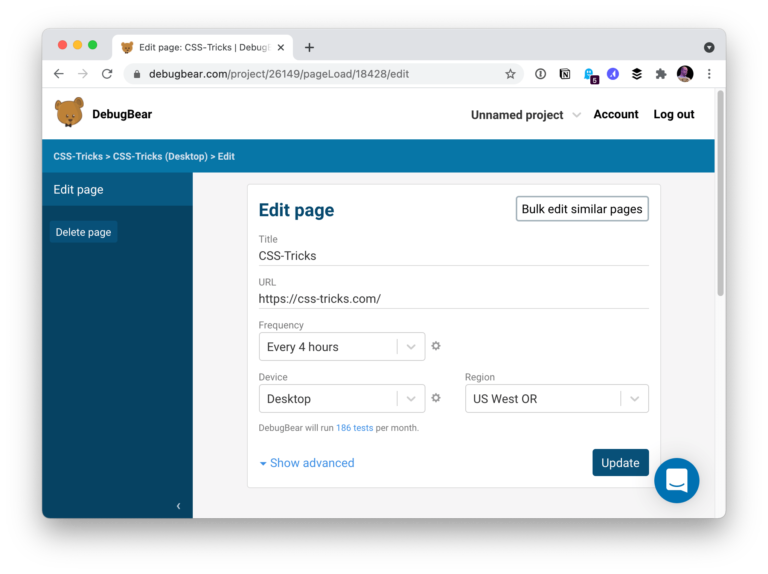

Square is paying $297 million in cash and stock for a “significant majority” of Tidal. Dorsey’s Twitter thread announcing the deal (of course) is vague about what Square intends to do with Tidal, but mentions things like “entirely new listening experiences” and “new complementary revenue streams.”

I’m grateful for Jay’s vision, wisdom, and leadership. I knew TIDAL was something special as soon as I experienced it, and I’m inspired to work with him. He’ll now help lead our entire company, including Seller and the Cash App, as soon as the deal closes. https://t.co/YRfYjcWJQx pic.twitter.com/xBtq2xfwue

— jack (@jack) March 4, 2021

It doesn’t take much imagination to come up with Square + Tidal rollouts in the future: A Square-enabled way for artists to sell T-shirts on tour, or even when they’re not on tour, for instance.

More intriguingly, given Dorsey’s love of All Things Blockchain, and the current mania over NFTs, it won’t be surprising to see Square + Tidal work on their own NFT scheme. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are blockchain-enabled digital pieces of … anything that investors and speculators and collectors are hoovering up at a crazy rate. Even if none of this makes sense to you, you may have heard about people paying real money — a lot of money — for digital ephemera like cartoon cat GIFs or animated trading cards of NBA players dunking or blocking. It’s a thing, for now.

So you can picture the Jay-Zs of the world selling songs, or snippets of songs, or the digital version of a lyric scribbled on a napkin, as NFTs, in deals that let Square and the artist get part of the deal.

If they get it out fast enough — while NFT mania booms — it’s easy to imagine many more headlines like these, except you’ll replace “Grimes” with “Beyonce” or whomever:

As long as you’re okay with the purely speculative hype around these kinds of sales and stories — and the understanding that some investors, including people who don’t fully understand what they’re doing, are going to make a lot of money, and some will get burned badly (see: GameStop, and also Cryptokitties, an early NFT gambit/gimmick that was kind of hot in 2018 and then cooled off but may be hot again) — then this all seems … okay? Maybe … good?

It certainly allows musicians — famous ones as well as ones you’ve never heard of — a chance to make money in an industry that currently offers them few options: Streaming music generally only pays out for enormously successful acts, and touring is hard work in the best of times. It’s also currently not available at all, due to the pandemic. The most optimistic version of the NFT story is that it allows artists (or anyone) to capture more of the value of the stuff they create than selling it through middlemen, like record labels or streaming services.

On the other hand: Even if you think the idea of Jay-Z selling five-second beatbox videos for millions of dollars and high-fiving Jack Dorsey is pretty awesome, none of this requires a $300 million deal to buy Jay-Z’s company. If Square wants to create new ways to help musicians sell real goods and digital goods, it could just do that.

Instead, Square is paying $300 million for a failed music service that doesn’t help it accomplish any of those goals.

A quick recap of the Tidal story: In 2015, Jay-Z bought an obscure Norwegian streaming service for $56 million, rebranded it, and launched it as an “artist-owned” streaming service. The idea was that Jay-Z had recruited other artists — like his wife Beyonce as well as Madonna, Rihanna, Daft Punk, and Kanye West — as partial Tidal owners, and Tidal would distinguish itself from competitors like Spotify by offering exclusive music on the service.

But in most cases, the artists involved in Tidal didn’t own their own music — big music labels did — so they couldn’t make their music exclusive on Tidal. And even the ones who did have that power, like Jay-Z, eventually relented and put their stuff on competitive services because that’s where all the listeners were.

For a while, it seemed like a big tech company, likely Samsung, might pay a lot to own Tidal, even if it wasn’t working. Apple had previously bought Beats for $3 billion as a way to vault itself into the streaming music business, so why not? But that deal never materialized, and in 2017, Sprint bought a third of Tidal and valued the company at $600 million.

Cut to Thursday’s deal, which values Tidal at something north of $300 million in an admission that Tidal hasn’t worked as a music service. And the thing about the ideas floating around the internet at this very moment, about selling Rhianna shirts or songs on Square are fine — but not related to Tidal. If Rhianna wants to do those deals, she can just do those deals. Tidal doesn’t own any of her rights to any of that.

So, what you’re really left with here is a deal that looks like a way for Jack Dorsey to move money from his publicly traded company to a company owned by a guy he likes to hang out with.

Which wouldn’t be the first time someone in a boring business has spent a lot of money to sidle up to an entertainment business. In fact, that dynamic is a core feature for Hollywood.

And while $300 million is a lot to you, a normal person, it is not much for Square: The company has $3 billion in cash on hand and likely paid for most of the deal with its stock, which, like many tech stocks, has been on a crazy tear and currently values the company at more than $100 billion.

So the real Square argument will be: Why not? If associating ourselves with Jay-Z, who we’ve also put on our board of directors, helps us convince people to buy and sell stuff on Square and talk about creating new paradigms for art and ownership, then great. And if not, it still sounds pretty cool.