You know that joke, “Two front-end developers walk into a bar and find they have nothing in common”? It’s funny, yet frustrating, because it’s true.

This article will present three different perspectives on accessibility in web design and development. Three perspectives that could help us bridge the great divide between users and designers/developers. It might help us find the common ground to building a better web and a better future.

Act 1

Table of Contents

“I just don’t know how developers don’t think about accessibility.”

Someone once said that to me. Let’s stop and think about it for a minute. Maybe there’s a perspective to be had.

Think about how many things you have to know as a developer to successfully build a website. In any given day, for any given job position in web development, there are the other details of web development that come up. Meaning, it’s more than “just” knowing HTML, CSS, ARIA, and JavaScript. Developers will also learn other things over the course of their careers, based on what they need to do.

This could be package management, workspaces, code generators, collaboration tools, asset loading, asset management, CDN optimizations, bundle optimizations, unit tests, integration tests, visual regression tests, browser integration tests, code reviews, linting, formatting, communication through examples, changelogs, documentation, semantic versioning, security, app deployment, package releases, rollbacks, incremental improvements, incremental testing, continuous deployments, merge management, user experience, user interaction design, typography scales, aspect ratios for responsive design, data management, and… well, the list could go on, but you get the idea.

As a developer, I consider myself to be pretty gosh darn smart for knowing how to do most these things! Stop and consider this: if you think about how many people are in the world, and compare that to how many people in the world can build websites, it’s proportionally a very small percentage. That’s kind of… cool. Incredible, even. On top of that, think about the last time you shipped code and how good that felt. “I figured out a hard thing and made it work! Ahhhhh! I feel amazing!”

That kind of emotional high is pretty great, isn’t it? It makes me smile just to think about it.

Now, imagine that an accessibility subject-matter expert comes along and essentially tells you that not only are you not particularly smart, but you have been doing things wrong for a long time.

Ouch. Suddenly you don’t feel very good. Wrong? Me?? What??? Your adrenaline can even kick in and you start to feel defensive. Time to stick up for yourself… right? Time to dig those heels.

The cognitive dissonance can even be really overwhelming. It feels bad to find out that not only are you not good at the thing you thought you were really good at doing, but you’ve also been saying, “Screw you, who cares about you anyway,” to a whole bunch of people who can’t use the websites you’ve helped build because you (accidentally or otherwise) ignored that they even existed, that you ignored users who needed something more than the cleverness you were delivering for all these years. Ow.

All things considered, it is quite understandable to me that a developer would want to put their fingers in their ears and pretend that none of this has happened at all, that they are still very clever and awesome. That the one “expert” telling you that you did it wrong is just one person. And one person is easy to ignore.

— end scene.

Act 2

“I feel like I don’t matter at all.”

This is a common refrain I hear from people who need assistive technology to use websites, but often find them unusable for any number of reasons. Maybe they can’t read the text because the website’s design has ignored color contrast. Maybe there are nested interactive elements, so they can’t even log in to do things like pay a utility bill or buy essential items on their own. Maybe their favorite singer has finally set up an online shop but the user with assistive technology cannot even navigate the site because, while it might look interactive from a sighted-user’s perspective, all the buttons are divs and are not interactive with a keyboard… at all.

This frustration can boil over and spill out; the brunt of this frustration is often borne by the folks who are trying to deliver more inclusive products. The result is a negative feedback cycle; some tech folks opt out of listening because “it’s rude” (and completely missing the irony of that statement). Other tech folks struggle with the emotional weight that so often accompanies working in accessibility-focused design and development.

The thing is, these users have been ignored for so long that it can feel like they are screaming into a void. Isn’t anyone listening? Doesn’t anyone care? It seems like the only way to even be acknowledged is to demand the treatment that the law affords them! Even then, they often feel ignored and forgotten. Are lawsuits the only recourse?

It increasingly seems that being loud and militant is the only way to be heard, and even then it might be a long time before anything happens.

— end scene.

Act 3

“I know it doesn’t pass color contrast, but I feel like it’s just so restrictive on my creativity as a designer. I don’t like the way this looks, at all.”

I’ve heard this a lot across the span of my career. To some, inclusive design is not the necessary guardrail to ensure that our websites can be used by all, but rather a dampener on their creative freedom.

If you are a designer who thinks this way, please consider this: you’re not designing for yourself. This is not like physical art; while your visual design can be artistic, it’s still on the web. It’s still for the web. Web designers have a higher challenge—their artistic vision needs to be usable by everyone. Challenge yourself to move the conversation into a different space: you just haven’t found the right design yet. It’s a false choice to think that a design can either be beautiful or accessible; don’t fall into that trap.

— end scene.

Let’s re-frame the conversation

These are just three of the perspectives we could consider when it comes to digital accessibility.

We could talk about the project manager that “just wants to ship features” and says that “we can come back to accessibility later.” We could talk about the developer who jokes that “they wouldn’t use the internet if they were blind anyway,” or the one that says they will only pay attention to accessibility “once browsers make them do it.”

We could, but we don’t really need to. We know how these these conversations go, because many of us have lived these experiences. The project never gets retrofitted. The company pays once to develop the product, then pays for an accessibility audit, then pays for the re-write after the audit shows that a retrofit is going to be more costly than building something new. We know the developer who insists they should only be forced to do something if the browser otherwise disallows it, and that they are unlikely to be convinced that the inclusive architecture of their code is not only beneficial, but necessary.

So what should we be talking about, then?

We need to acknowledge that designers and developers need to be learning about accessibility much sooner in their careers. I think of it with this analogy: Imagine you’ve learned a foreign language, but you only learned that language’s slang. Your words are technically correct, but there are a lot of native speakers of that language who will never be able to understand you. JavaScript-first web developers are often technically correct from a JavaScript perspective, but they also frequently create solutions that leave out a whole lotta people in the end.

How do we correct for this? I’m going to be resolute here, as we all must be. We need to make sure that any documentation we produce includes accessible code samples. Designs must contain accessible annotations. Our conference talks must include accessibility. The cool fun toys we make to make our lives easier? They must be accessible, and there must be no excuse for anything less This becomes our new minimum-viable product for anything related to the web.

But what about the code that already exists? What about the thousands of articles already written, talks already given, libraries already produced? How do we get past that? Even as I write this article for CSS-Tricks, I think about all of the articles I’ve read and the disappointment I’ve felt when I knew the end result was inaccessible. Or the really fun code-generating tools that don’t produce accessible code. Or the popular CSS frameworks that fail to consider tab order or color contrast. Do I want all of those people to feel bad, or be punished somehow?

Nope. Not even remotely. Nothing good comes from that kind of thinking. The good comes from the places we already know—compassion and curiosity.

We approach this with compassion and curiosity, because these are sustainable ways to improve. We will never improve if we wallow in the guilt of past actions, berating ourselves or others for ignoring accessibility for all these years. Frankly, we wouldn’t get anything done if we had to somehow pay for past ignorant actions; because yes, we did ignore it. In many ways, we still do ignore it.

Real examples: the Google Developer training teaches a lot of things, but it doesn’t teach anything more than the super basic parts of accessibility. JavaScript frameworks get so caught up in the cleverness and complexity of JavaScript that they completely forget that HTML already exists. Even then, accessibility can still take a back seat. Ember existed for about eight years before adding an accessibility-focused community group (even if they have made a lot of progress since then). React had to have a completely different router solution created. Vue hasn’t even begun to publicly address accessibility in the core framework (although there are community efforts). Accessibility engineers have been begging for inert to be implemented in browsers natively, but it often is underfunded and de-prioritized.

But we are technologists and artists, so our curiosity wins when we read interesting articles about how the accessibility object model and how our code can be translated by operating systems and fed into assistive technology. That’s pretty cool. After all, writing machine code so it can talk to another machine is probably more of what we imagined we’d be doing, right?

The thing is, we can only start to be compassionate toward other people once we are able to be compassionate toward ourselves. Sure, we messed up—but we don’t have to stay ignorant. Think about that time you debugged your code for hours and hours and it ended up being a typo or a missing semicolon. Do you still beat yourself up over that? No, you developed compassion through logical thinking. Think about the junior developer that started to be discouraged, and how you motivated them to keep trying and that we all have good days and bad. That’s compassion.

Here’s the cool part: not only do we have the technology, we are literally the ones that can fix it. We can get up and try to do better tomorrow. We can make some time to read about accessibility, and keep reading about it every day until we know it just as well as we do other things. It will be hard at first, just like the first time we tried… writing tests. Writing CSS. Working with that one API that is forever burned in our memory. But with repetition and practice, we got better. It got easier.

Logically, we know we can learn hard things; we have already learned hard things, time and time again. This is the life and the career we signed up for. This is what gets us out of bed every morning. We love challenges and we love figuring them out. We are totally here for this.

What can we do? Here are some action steps.

Perhaps I have lost some readers by this point. But, if you’ve gotten this far, maybe you’re asking, “Melanie, you’ve convinced me, but what can I do right now?” I will give you two lists to empower you to take action by giving you a place to start.

Compassionately improve yourself:

- Start following some folks with disabilities who are on social media with the goal of learning from their experiences. Listen to what they have to say. Don’t argue with them. Don’t tone police them. Listen to what they are trying to tell you. Maybe it won’t always come out in the way you’d prefer, but listen anyway.

- Retro-fit your knowledge. Try to start writing your next component with HTML first, then add functionality with JavaScript. Learn what you get for free from HTML and the browser. Take some courses that are focused on accessibility for engineers. Invest in your own improvement for the sake of improving your craft.

- Turn on a screen reader. Learn how it works. Figure out the settings—how do you turn on a text-only version? How do you change the voice? How do you make it stop talking, or make it talk faster? How do you browse by headings? How do you get a list of links? What are the keyboard shortcuts?

Bonus Challenge: Try your hand at building some accessibility-related tooling. Check out A11y Automation Tracker, an open source project that intends to track what automation could exist, but just hasn’t been created yet.

Incrementally improve your code

There are critical blockers that stop people from using your website. Don’t stop and feel bad about them; propel yourself into action and make your code even better than it was before.

Here are some of the worst ones:

- Nested interactive elements. Like putting a button inside of a link. Or another button inside of a button.

- Missing labels on input fields (or non-associated labels)

- Keyboard traps stop your users in their tracks. Learn what they are and how to avoid them.

- Are the images on your site important for users? Do they have the alt attribute with a meaningful value?

- Are there empty links on your site? Did you use a link when you should have used a button?

Suggestion: Read through the checklist on The A11y Project. It’s by no means exhaustive, but it will get you started.

And you know what? A good place to start is exactly where you are. A good time to start? Today.

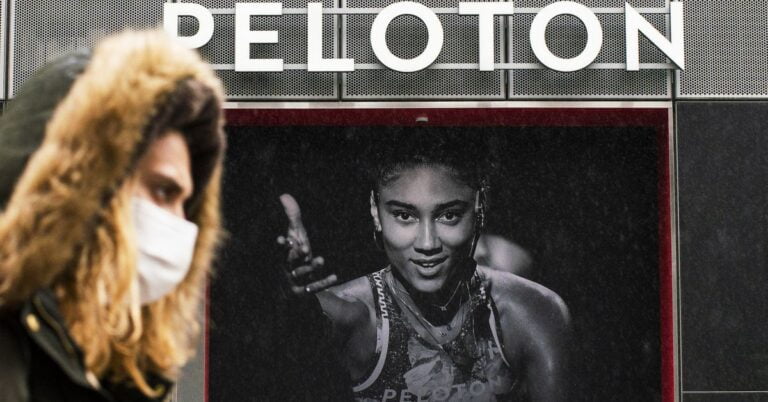

Featured header photo by Scott Rodgerson on Unsplash