This story is part of a Recode series about Big Tech and antitrust. Over the next few weeks, we’ll cover what’s happening with Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and Google.

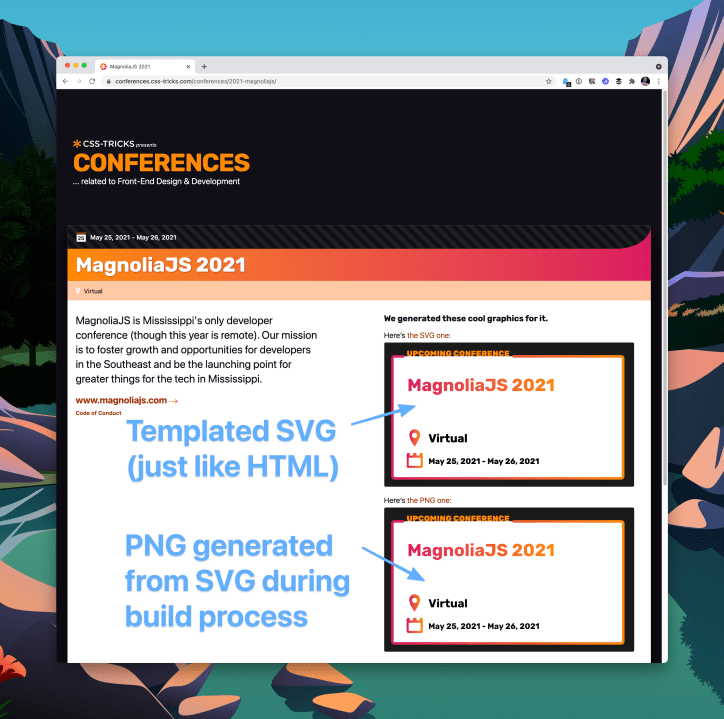

It wasn’t immediately clear what Mark Zuckerberg wanted to do with Oculus when Facebook bought the virtual reality headset maker back in 2014. Those plans are now coming into focus: Facebook is now called Meta, and it’s not just a social media company, it’s a metaverse company. And as the new name implies, Meta wants to win in this space, just as Facebook won in social media.

But a growing group of regulators, politicians, and advocacy groups are raising concerns about Meta’s plans in this realm.

The company formerly known as Facebook spent nearly two decades cementing its position as the biggest social media company in the world — in large part by buying other social media startups, like Instagram and WhatsApp. Critics have accused Mark Zuckerberg and his company of using a “copy-acquire-kill” strategy to pressure its would-be competition into selling or risk being crushed by Facebook.

Now, some are concerned that Meta may be employing the same tactics in the metaverse, a concept that Zuckerberg describes as “an embodied internet where you’re in the experience, not just looking at it.” In practical terms, the metaverse is a virtual space where people wearing AR/VR headsets can interact with each others’ avatars, play games, have meetings, and so on. While Meta is still in the early stages of developing the futuristic hardware and software that will make this possible, the company is already a market leader. Meta’s VR headsets made up an estimated 75 percent of all AR/VR headset shipments in the first quarter of 2021. And as Recode’s Peter Kafka has reported, the social media giant has been quietly buying up companies in the metaverse, acquiring at least five AR/VR-related companies in the past year.

Regulators are paying attention. The FTC and several state attorneys general are investigating whether Meta is using monopolistic practices in the AR/VR market, according to a January Bloomberg report. The Information reported that the FTC is taking a close look at Meta’s planned acquisition of Within, the company behind the popular VR fitness game Supernatural. In a new report highlighting Meta’s metaverse-related acquisitions, the Tech Oversight Project, an antitrust advocacy group, claimed that the company was using “its same playbook to squash potential competition,” as it has in the past.

Meta’s critics are especially skeptical about the company buying up metaverse companies because of its contentious acquisitions in the past, particularly Instagram and WhatsApp. The FTC and 48 states and territories sued Facebook over these purchases at the end of 2020, drawing on internal emails showing how Facebook executives allegedly strategized to get rid of the company’s competitors, including Zuckerberg saying that it’s “better to buy than compete.” The states’ case was dismissed (a decision the states are appealing), but the FTC’s is still going. Meta now argues that the government is backtracking and going after deals that it approved years ago.

Antitrust regulators argue that Meta is an unbeatable social media behemoth, but in recent weeks, Meta has suffered a series of setbacks that might make it harder for that argument to stand. After a fourth-quarter earnings report showed shrinking user growth on the Facebook app, Meta’s stock price took a historic dip, losing more than $250 billion in market value in a day, the largest ever single-day drop for a US company. Executives blamed the bad news, in part, on competition from TikTok, which is popular with younger users Facebook is struggling to attract.

That Meta is losing relevance in the social media market is a very real threat for the company. It’s also why, even though the technology is still largely hypothetical, the potential regulation of the metaverse — not social media regulation — could become the more worrisome long-term threat for Meta, one that could slow down the company at a time when it needs to reinvent itself to succeed.

“Investing in and building products that consumers want is the key to success,” said Meta company spokesperson Christopher Sgro. “We cannot build the metaverse alone — collaboration with developers, creators, and experts will be critical. As we invest in the metaverse, we know that we face fierce competition from companies like Microsoft, Google, Apple, Snap, Sony, Roblox, Epic, and many others at every step of this journey.”

Some people in Washington want to take action before Meta has the chance to corner an emerging market once again. That may require changing existing antitrust laws, which critics say are too narrow. Antitrust regulations have also historically relied on the cost of goods to consumers and don’t take into account the modern digital economy, where services like Facebook and Instagram are free. Whatever regulators and lawmakers decide to do with Meta will have reverberations throughout Silicon Valley and might define the fight to break up Big Tech.

Anti-competitive concerns in the metaverse

Table of Contents

Some competitors are already complaining that Meta isn’t playing fair in the new metaverse market. Mark Zuckerberg has said that he wants the metaverse to allow other companies to build in this space. But some independent developers argue that Meta isn’t as open as it says it is.

One big issue: Some AR/VR hardware companies say Meta is discounting its VR headsets to the point that it’s hard for smaller startups to compete. Meta’s Quest 2 headset currently costs $299, which is several hundred dollars below any comparable device on the market. The FTC is reportedly looking into the possibility that Meta is selling Quest headsets at a loss in an attempt to undercut competitors and drive them out of the market, a practice known as predatory pricing.

“No one can put a product on the market at the price they’re at today, with the same kind of capabilities,” Stan Larroque, founder of the Paris-based AR/VR startup Lynx, told Recode. The company plans to release its first consumer headset, which Larroque says will have more advanced features than the Quest 2, for $700. “My name is not Mark Zuckerberg. I cannot sell my product at a loss.”

Larroque added that Meta has tried to poach his team of engineers with offers of higher salaries, but his staff stayed on. Larroque also said he’s spoken with various regulatory agencies and lawmakers in the US and Europe about Meta’s business practices. Meta declined to comment on Larroque’s claims.

But Meta’s lower price for its headsets is not necessarily an antitrust violation. Predatory pricing cases are very difficult to prove. The current law says below-cost pricing is only illegal if it’s done by a dominant company in order to run competitors out of business, allowing it to raise its prices above market levels to recoup its losses once it has a monopoly. Courts generally see low prices as good for consumers, even if they come at the expense of competitors.

Another topic that’s come under scrutiny is whether Meta’s metaverse is truly open to third-party software developers. Currently, Meta operates an AR/VR app store — similar to Apple’s App Store or Google’s Play Store — for which developers can create software for its headset. Meta, like Apple and Google, takes a 30 percent cut of any purchases made in the apps. Meta has also required users to sign in with Facebook accounts, a requirement that’s raised concerns about the company creating a walled garden. (Following an outcry from many gamers, Meta said it plans to end the Facebook account requirement.)

Developers have raised other concerns about how Meta operates its app store. Some have accused the company of blocking rival apps from being carried on Meta’s Quest AR/VR app store, or of copying the competition outright. For example, Meta’s Horizon Worlds social space is similar to the popular game Rec Room, and the company’s “Horizon Workrooms” virtual work conferencing software looks a lot like a collaboration app from a company called Spatial. (Spatial has since pivoted to NFTs rather than VR; the company’s head of growth Jacob Loewenstein told Recode that the reason for the pivot wasn’t because Meta copied Spatial but because of growing business opportunities around NFTs, artists, and creators.)

Meta has also acquired some of the most popular third-party games for the Quest headset, including not only Supernatural but also Beat Saber, which is one of the most popular games in VR and currently listed among top-selling games in Meta Quest’s app store.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of developers who feel they don’t even have a chance to enter the market because Facebook is buying up the technology that they’re trying to develop,” Llamas, from VoxPop, said. On the other hand, Meta’s AR/VR can be beneficial for the industry since the company can pour resources into developing startups and hardware to scale to a wider audience, she added.

In response to concerns about whether its AR/VR platform is truly open to third-party developers, Meta pointed to the fact that the company still allows the games it has acquired to run on third-party gaming systems.

As AR/VR becomes a more mainstream technology — and as Quest headsets capture a larger share of the market — whether or not Meta is giving its own products an advantage will become a higher stakes battle.

How Meta became an antitrust target

The metaverse is still very much part of a hypothetical future, which makes accusations that Meta is monopolizing it now tough to prove. And while Meta has had issues with the FTC in the past — including a record $5 billion fine over Facebook privacy violations a few years ago — the agency allowed it to acquire the companies that helped it become the dominant force it still is today. The FTC is reconsidering that now.

In their lawsuits against Meta, the FTC and attorneys general argued that the company’s acquisitions and anti-competitive practices helped it dominate social media and protected it from competition in up-and-coming spaces like mobile and messaging, which it was unable to do on its own. Other companies found their access to Facebook’s platform restricted or limited if they worked with competitors or were competitors themselves.

Meta says the FTC hasn’t proved that Meta has a social media monopoly. Meta Vice President and General Counsel Jennifer Newstead said that the FTC “cleared these acquisitions years ago,” and that the government “now wants a do-over, sending a chilling warning to American business that no sale is ever final.” Meta has scored one victory in the case, when a judge threw out the states’ lawsuit and said the FTC needed to make a better case that Meta had a social media monopoly. The FTC refiled a longer, more detailed complaint that so far has been allowed to move forward over Meta’s objections.

Meanwhile, other parts of the world may have lost some of their appetite for Meta mergers. The company’s attempt to buy Giphy, a generator and database of GIFs, is being fought by antitrust regulators in the United Kingdom, which fined the company millions of dollars and ordered it to sell Giphy off (Meta has appealed, and the acquisition is on hold until it’s resolved). But after more than a year of scrutiny, Meta’s $1 billion acquisition of customer service software company Kustomer finally went through after Meta secured approval from regulators in the UK, US, and EU, so not every Meta merger is being blocked.

In any case, Meta maintains that it has plenty of competitors, an argument that may be helped by its recent quarterly earnings.

“If Facebook is losing market power, that would be relevant to the FTC’s lawsuit,” Rutgers Law professor Michael Carrier said. “The suit challenges Facebook’s conduct not just at the time of the acquisitions but also continuing to the present.”

The history of antitrust cases against big, disruptive technology companies shows that the government doesn’t have to win to have an impact. The DOJ sued IBM and Microsoft for monopolizing the mainframe and operating system markets, respectively. Those cases ended up being dropped or settled, but miring the companies in years of litigation during technological shifts allowed for competitors to emerge.

Meta’s unclear future

The IBM and Microsoft cases show how antitrust action can distract or discourage tech companies from new markets; in those cases, personal computing and the mobile internet, respectively. It’s still too early to say if Meta will be similarly impacted.

The cases also show the gap between the fast-moving technology industry and the government’s response, which is notoriously slow. It can take decades for antitrust cases to be resolved. Attempts to reform legislation can take even longer.

“There’s a real problem in Washington where we’re always fighting the fight from five years ago, or sometimes we’re fighting the fight from 10 years ago. And it makes it really difficult to ever get ahead of things,” Charlotte Slaiman, competition policy director at Public Knowledge, said.

The FTC isn’t ignoring the metaverse, either. When the agency re-filed its complaint against Meta last year, it included a new section about the metaverse. The agency noted that Meta’s pattern of cutting off access to its platform for developers who work with competitors, or whose apps directly compete with Meta’s services, is “likely” to occur whenever the company faces competition from new technologies. The metaverse was cited as an example of one of those new technologies.

That doesn’t mean the agency can do something about Meta and its metaverse ambitions anytime soon. Antitrust cases are tough enough to prove in established markets, let alone emerging ones. But that may be a fight the FTC or the DOJ’s antitrust division — which was reportedly looking into Facebook’s VR acquisitions back in 2020 — wants to take on, now that both are led by vocal critics of Big Tech’s power over the economy.

“The argument that the VR market is too new [or] unknown could have worked a few years ago, but today, it could provide an enticing test case for agencies intent on showing that they will vigorously enforce the antitrust laws against ‘nascent competitors,’” Carrier explained.

The FTC may get some help from lawmakers. Bipartisan antitrust bills specifically targeted at Big Tech companies and digital platforms are making their way through Congress. One bill, the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act, would forbid dominant companies from acquiring competitors — or potential competitors — in order to reinforce their monopoly power. If it passes, Meta may not be able to continue to make acquisitions in certain markets, including the metaverse, according to Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the Institute of Local Self-Reliance.

But the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act seems to have stalled in Congress, which has yet to give any of the Big Tech antitrust bills a floor vote in either house. The bill’s Senate co-sponsors, Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Tom Cotton, didn’t comment to Recode on its progress. Advocates have become increasingly worried at how little time is left in this session.

In the meantime, the FTC and the DOJ are currently working on new merger guidelines that the agencies said will better address modern markets and what they will consider when deciding whether to approve mergers. But it will be at least a year before those guidelines are complete.

There are other hurdles when it comes to regulators’ plans to rein in Meta. Without increased funding from Congress, the FTC has limited resources and has to pick its battles, especially when it comes to fighting massive companies, including the other Big Tech companies, that can afford an army of lawyers to fight back. FTC chair Lina Khan may decide an emerging market like AR/VR isn’t the hill she wants to die on.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about how exactly the metaverse will shake out. It’s possible that Meta’s plans may fail not just due to regulation, but business realities.

Putting aside the debate about competing tech giants in the metaverse, the masses may not want to engage with this alternate reality at all. Zuckerberg’s announcements about the metaverse have been met with a good deal of confusion and skepticism. And let’s not forget that, a decade ago, Google Glass — that company’s early attempt at an augmented reality headset — notoriously flopped because it just wasn’t popular with everyday users, many of whom found it privacy-invasive and uncool. Only about a quarter of Americans have ever used an AR or VR headset, and just 28 percent say they’re excited by the technology, according to a July Morning Brew-Harris poll.

And let’s not forget Meta’s history of privacy problems and content moderation issues that have contributed to users losing trust in the company. That means people might be reluctant to give Meta more access to even more personal data that AR/VR headsets can collect, like our eye movements and facial expressions.

Regardless of how successful or not Meta’s business plans in the metaverse are, having the looming threat of regulation hanging over its head isn’t helping. Regulation could slow Meta during a critical moment for the company when it needs to reinvent itself. What’s clear is that no matter what happens, regulators are trying to get ahead of the metaverse, and Meta won’t be able to skate by as easily as it has in the past.