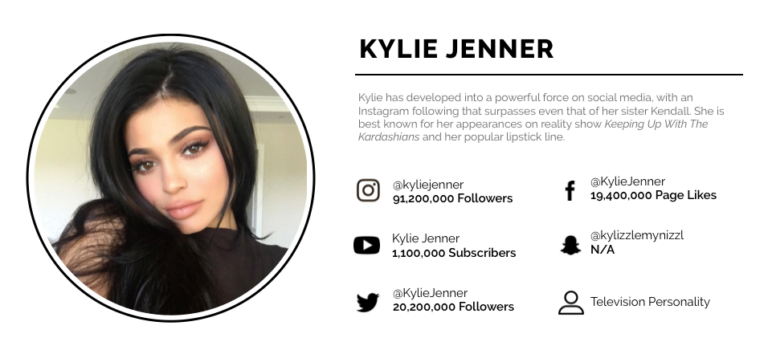

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has faced a backlash since Politico reported earlier this week that he indirectly funds and wields unusually heavy influence over an important White House office tasked with advising President Joe Biden’s administration on technical and scientific issues.

The ethical concerns surrounding this news are glaring: A tech billionaire with an obvious personal interest in shaping government tech policy is giving money to an independent government agency devoted to tech and science, albeit through his private philanthropic foundation.

The real scandal, however, is that a government office needed philanthropic aid to fund its work in the first place, creating an ethical quandary over potential conflicts of interest.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) is responsible for advising the president on a vital and wide breadth of public policy — whether it’s “a people’s Bill of Rights for automated technologies” or the gargantuan effort of preparing for future pandemics. It also has a meager $5 million annual budget — which means it has to get creative to do its work.

“The use of staff from other federal agencies and the armed services, universities, and philanthropically funded nonprofits dates back five presidential administrations — but President Biden was the first to elevate the office to Cabinet level,” an OSTP spokesperson said in a statement to Recode.

According to the office, among the 127 people who currently work there, only 25 are OSTP employees. The remaining are a mix of temporary appointees from other federal agencies, as well as people from universities, science organizations, or fellowships that may be funded by philanthropy.

Enter Schmidt Futures, Schmidt’s private nonprofit that supports initiatives that use tech to address “hard-to-solve’’ scientific and societal problems. According to Politico, there was direct coordination between OSTP and a Schmidt Futures employee named Tom Kalil to secure funding for the office staff. Kalil had also served as an unpaid consultant to OSTP for four months while still working for Schmidt Futures, and he left the agency after ethics complaints in October 2021. The ties between Schmidt, his foundation, and OSTP go even deeper than that, with Politico reporting that “more than a dozen officials in the [then] 140-person White House office have been associates of Schmidt’s, including some current and former Schmidt employees.”

Both OSTP and Schmidt Futures maintain that their connection has been misconstrued as nefarious; they say this sort of partnership is par for the course.

In a statement, Schmidt Futures highlighted how the OSTP has been “chronically underfunded,” and said that it was proud to be among the “leading organizations” providing funding to OSTP. In other words, Schmidt Futures makes clear that it isn’t the only private organization to charitably provide much-needed monetary support to government agencies.

“The United States Government and the OSTP have used pooled philanthropic funding to ensure proper staffing across agencies for over 25 years,” the statement continues.

It’s true that collaboration between governments and the philanthropic sector is not new. “Over the last two decades, there’s been an increased focus on public-private partnerships at the federal level, including using private resources to fund public and governmental capacity,” said Benjamin Soskis, senior research associate in the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy at the Urban Institute. “Where this gets really tricky is when the funding involves regulatory agencies with oversight over areas that the funder has been interested in.” That’s why Schmidt’s connections to OSTP have raised alarms.

“This has been a problem for philanthropy and democracy really from the beginning of the emergence of large-scale foundations in the early 20th century,” Soskis continued. “A number of them, most significantly the Rockefeller Foundation, appreciated that shaping public policy and helping to staff federal institutions and federal agencies was a way to leverage their resources most effectively.”

Many government offices, like OSTP, also work with outside consultants from the private sector. Some are what’s known as “special government employees” (SGE) — they can work for the government for up to 130 days over a 365-day period, are subject to different ethics rules, and can be compensated through outside funding. According to Walter Shaub, a senior ethics fellow at the Project on Government Oversight, roughly 40,000 SGEs are working for the government today, most of them on federal advisory committees.

“Outsiders are not subject to government ethics rules or the government’s transparency requirements,” Shaub continued. “They may put their own interests before the American people, and we have no way of knowing how that changes outcomes.”

It’s one thing for the public and private sectors to coordinate on and contribute to a project — it’s another when a government office accepts money from philanthropy that creates potential ethical conflicts. That signals a systematic underfunding of the public sector that all but guarantees some dependence on private interests, and accepting such money creates a problematic trade-off.

Speculating on the true motive behind Schmidt’s involvement in OSTP is almost beside the point. It seems inevitable that the money quietly flowing from him and his foundation to the office would apply pressure that favors Schmidt’s personal and business interests.

“It’s a form of shaping public policy,” said Soskis. “You can do that through trying to promote certain laws, but you can also do that through staffing. And I don’t think that’s necessarily nefarious, but it’s certainly a type of influence.”

“There’s got to be, at a bare minimum, a clear understanding of what money is entering the arena, from who, and for what purpose,” said Peter Goodman, a New York Times economics journalist and author of Davos Man: How the Billionaires Devoured the World. “In a post-Citizens United world, combined with these ‘innovative’ — I’m using that term in air quotes — approaches to philanthropy, they raise very troubling questions.”

What’s at stake here is a much larger issue than Eric Schmidt and the OSTP. It’s a question of what kind of presence private philanthropy should have in government. Government is expected to be fairly transparent and accountable to the public, while the philanthropy world is often opaque and subject to the whims of private, ultra-wealthy individuals like Schmidt, whose estimated net worth is $27 billion.

What would more reliably ensure government agencies charged with developing public policy can remain at a distance from the desires of the private sector? It could start with the government adequately funding them.

As Politico’s investigation of Schmidt Futures made the news, President Biden unveiled a yearly federal budget proposal that includes a 20 percent tax on households worth more than $100 million. It’s significant in that it would tax unrealized capital gains — as in, the profit someone would make if they sold assets like company stock. It’s an attempt to indirectly tax wealth instead of just income. The White House estimates that over half the estimated $360 million in revenue that would be generated from the tax would come from billionaires like Schmidt.

That kind of funding would have been helpful two years ago when the federal government’s sluggish failure of a pandemic response led billionaires, particularly tech billionaires like Bill Gates, to step up and help the public.

But Goodman questioned whether billionaires filling in for the government is something to celebrate. “Why are we dependent upon a tech bro being generous, in what’s supposed to be the richest country on Earth in the worst pandemic in a century, to outfit our medical workers?” he asked.

Fiscal austerity tends to increase the government’s reliance on private-public partnerships, since government agencies find themselves strapped for resources, and this helps normalize the idea that the private sector can handle crises and other matters of public interest more efficiently or innovatively than the government can.

Goodman described the typical playbook for expanding the private sector’s reach: “First you cut the budget for government programs, then you do a study that shows that government programs are not that effective. Then you say, ‘government is a hopeless failure, let’s just dismantle this government program altogether,’” he said. Then whatever problem is at hand is turned over to the private philanthropic sector, whose proponents will say that they can do more good than the government could — and they have more of a justification for why they should pay less in taxes.

“This is the story of American capitalism of the last 50 years,” said Goodman.

This playbook attempts to argue, at the very least, that the government can’t govern alone. It needs the significant backing of private generosity. And that generosity is partly fueled by a tax system that allows the very wealthy to owe very little. The 25 wealthiest Americans pay a “true tax rate” of about 3.4 percent.

Many of these billionaires do give significant sums of money to philanthropic causes, often by setting up their own private foundations where they can control how their wealth influences society, all the while giving their reputations a boost. “But when we get into the public actually exercising our democratic rights to determine how much tax [billionaires are] going to pay so we can finance things regularly in a dependable fashion, suddenly [the reaction is]: ‘no way,’” Goodman said.

One positive sign is that OSTP’s budget is likely to increase. Congress increased its budget to $6.65 million in the omnibus spending bill earlier this month, and Biden’s yearly budget proposal would give OSTP $7.9 million a year. But how much this increase would change the makeup of OSTP-funded staff remains to be seen.

“It’s not that [Schmidt] shouldn’t have a seat at the table,” Goodman said. “It’s that we can’t just outsource our problems to billionaires who are always going to have conflicts of interest.”