For Reese Mercado, the decision to unionize came after they watched a customer physically assault a former coworker over enforcing vaccine requirements at their Starbucks store. For Hayleigh Fagan, it was when she got a company-wide letter from the Starbucks Vice President telling employees not to unionize. For Hope Liepe, it was the hypocrisy of calling employees “partners” but not treating them that way.

Since the first corporate Starbucks location voted to unionize late last year, 10 others have voted. Only one store has voted against unionizing. The latest and largest Starbucks to unionize is the company’s flagship store in Manhattan, which voted 46-36 on Friday to unionize. One of just three Starbucks roasteries in the country, this location is an important milestone for the Starbucks union since it has many more employees than a typical Starbucks (nearly 100) and shows that the Starbucks union can be successful in the company’s manufacturing arm as well. Even more notable, they’ve voted yes in the notoriously difficult-to-unionize food services industry, where high rates of turnover and a more easily replaceable workforce make union organizing extremely difficult.

Starbucks employees around the country say they’re seeing successful union votes at other locations and thinking they could improve conditions at their own stores by doing the same. Some 160 other locations in 28 states are slated to vote in the coming weeks and months.

They’re hoping to use collective bargaining to get a number of improvements, including higher pay, more hours, and better safety protections, a more necessary change since the erstwhile latte makers became front-line workers during the pandemic. They want more say in what their working lives are like, and they want to hold a company that talks of progressive values accountable.

As Liepe, an 18-year-old barista in Ithaca, New York, put it, “We want to be able to sit down with Starbucks, with the higher-up executives, and make a plan so that we, as employees, feel as valued as they say that we are.”

Starbucks said in a statement, “We are listening and learning from the partners in these stores as we always do across the country.”

While the unionizing Starbucks stores so far only represent a small portion of the chain’s roughly 9,000 company-run locations, its number belies its importance. It’s a spark of optimism in a union movement that has been in decline for decades. And as unions have become less prevalent in the American workforce, so have the worker benefits and protections unions afforded, including health care, pensions, and paid time off. Along with several other high-profile union efforts at a range of companies, including Amazon, John Deere, and the New York Times, Starbucks workers could help stanch or even reverse that decline.

Ileen DeVault, professor of Labor History at Cornell University, said it’s unprecedented for a national chain of small food and beverage stores to unionize, and that Starbucks’s efforts could have knock-on effects.

“It’s pretty amazing that a company that large and that present in American consciousness — everybody knows what Starbucks is — is unionizing,” DeVault told Recode.

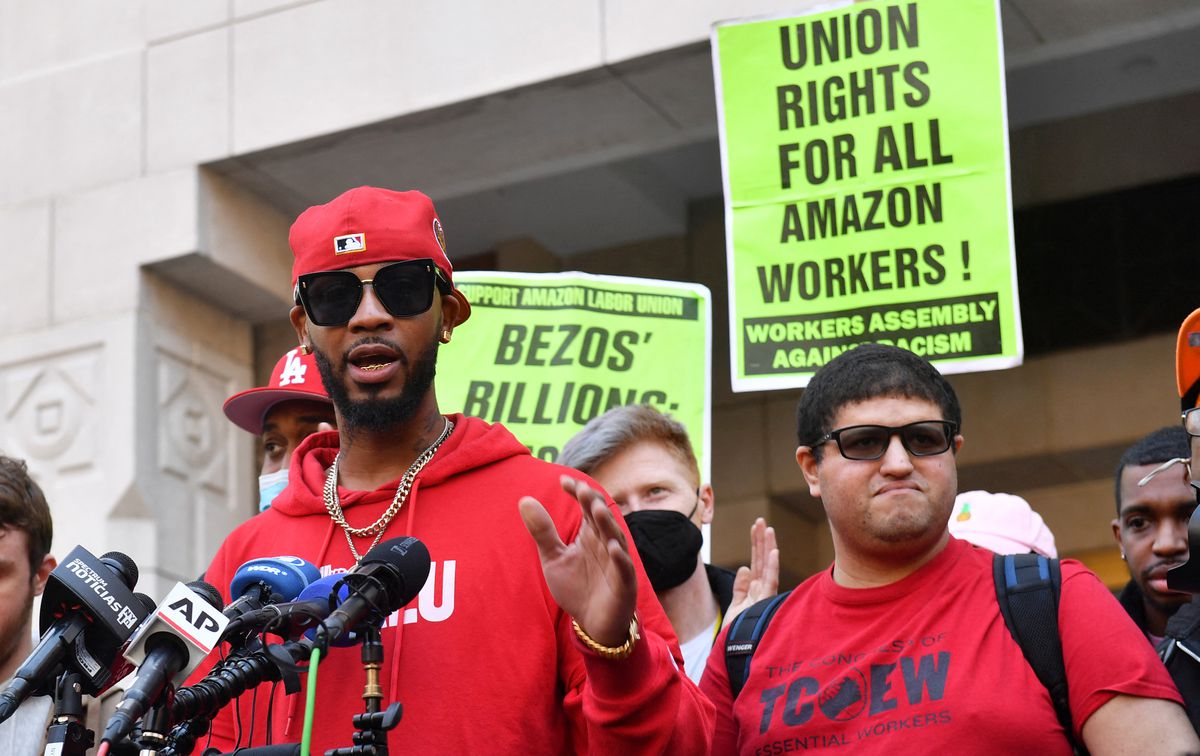

While unionization is popular and gaining a lot of attention, it’s still incredibly difficult. That means high-profile failures as well. Just last week, an Amazon warehouse in Alabama voted against unionizing. This was union organizers’ second try — the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) said the e-commerce giant had violated labor law by giving the impression it was monitoring which workers voted, so ordered a re-vote. But workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island just became part of the first Amazon union in the country — and they did so with a worker-led union much like the one at Starbucks.

For now, the actions at Starbucks provide a case study for how other Americans might try to organize and where the union movement might go from here.

“The scale, the energy, the pace,” said Richard Minter, vice president of the Workers United union. “There’s nothing like it in labor history.”

What it takes to unionize a Starbucks

Table of Contents

Workers at the Genesee Street Starbucks in Buffalo were murmuring about starting a union back in 2019. But it wasn’t until the spring of 2021, after the pandemic had laid bare the treacherous situation of food service workers and the Great Resignation had given employees more leverage, that they started getting serious. They reached out to the local chapter of Workers United, a union affiliated with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), for guidance and formed a committee of workers from area Buffalo stores.

As each additional store organizes, it inspires more to do so. Most of the workers we spoke to mentioned getting inbound inquiries from workers at other locations near and far after they went public with their intent to unionize.

“It seems like every time we win another one, we get tremendous outreach from markets all across the country,” Minter said. He added that after the first Starbucks in Washington, the company’s home state, voted to unionize, Workers United received 30 new contacts from other stores that night.

Each store’s organizing effort is an asset to the next. From these other stores, new organizers learn what works and what doesn’t, not to mention what to expect from corporate and how to respond. They know the company might make misleading claims about the price of unions. They also know the company will hold meetings during their shifts to convince them not to join the union. These are called captive audience meetings, which many workers find intimidating.

“When you connect with [other workers across the country] you get to share your experiences with them and they get to share theirs and guide you through the process,” said Caro Gonzalez, a Starbucks shift supervisor in Austin who’s majoring in advertising at the University of Texas. “That support is really huge.”

Communicating with other stores made employees realize that they have more similarities than differences. It has built an immense feeling of solidarity, so that these small shops, each with roughly 20-30 workers, feel like they’re part of something much bigger.

“Before winning in Buffalo, we didn’t know if it was possible,” Michelle Eisen, 39, a barista at that first unionized Starbucks, told Recode. “I think these stores have that kind of optimism to know that it can be done.”

But that doesn’t mean their route will be easier. Eisen added, “These newer stores that are coming on board almost need more courage than we did because they know what they’re about to get involved in, they know what the company is capable of, and they’re still choosing to do this.”

Why unionizing is working at Starbucks

What’s made the Starbucks efforts so successful is what Rebecca Givan, associate professor of labor studies at Rutgers University, calls a “perfect storm” of circumstances, in addition to strategic decisions like organizing by store and communicating with other stores. Those particulars can help guide what will and won’t work elsewhere.

To begin with, Starbucks is a company that espouses progressive values, from single-origin coffee beans to LGBTQ rights. But when those values come up short — claiming that Black Lives Matter while calling the cops on Black customers, offering gender-affirming medical treatment that’s hard to access in practice, and advertising fertility treatment that can cost more than people’s paychecks — it can work against the company.

“Starbucks is quote-unquote ‘progressive,’ ‘woke,’ whatever. They give us decent benefits,” Fagan, a 22-year-old shift supervisor in Rochester, said. “But we’re literally selling our lives and time and bodies to this corporation. Tell me why I don’t deserve a living wage.”

But while that pay is much higher than the industry average of about $12 an hour, many of the workers we talked to said it wasn’t enough, especially as they said their hours have been cut back. These cutbacks could jeopardize employees’ access to Starbucks’s health insurance — a rarity in the food service world — since employees need to work at least 20 hours a week to be eligible for those benefits. Others see the cuts in hours as a way to drive out existing employees in order to tamp down union organizing.

Starbucks denied that it’s cutting back hours.

“We always schedule to what we believe the store needs based on customer behaviors,” spokesperson Reggie Borges told Recode. “That may mean a change in the hours available, but to say we are cutting hours wouldn’t be accurate.” The company added that eligibility to health care was measured just twice a year by average hours worked, rather than on a weekly basis, so a short-term cut in hours wouldn’t affect health care eligibility.

In any case, Starbucks’s perceived progressive values often attract young workers who share those values. Many of the Starbucks workers trying to unionize are in their early 20s. They’ve become adults amid huge social justice movements like Black Lives Matter and Me Too. They are comfortable with empathy and technology, making them star candidates for a resurgent union movement. In addition to talking to other Starbucks workers across the country on Zoom and social media, they hash out their store strategies over Discord while sharing viral videos about unions on TikTok. On a press call following her Mesa, Arizona, store’s vote to unionize in March, barista Haley Smith called Twitter “the rising star of our campaign.”

Working through the pandemic made the situation and worker safety especially acute.

“They’ll call me a partner all they want, but corporate will allow me to die on the floor if it made them money,” said Brandi Alduk, a 22-year-old employee at a Queens Starbucks store, noting that she was exaggerating but with some truth. She said company executives rolled back Covid-19 restrictions “a little too soon and a little too brazenly, considering they were still working at home when they started loosening some of the restrictions.”

One positive aspect of working during the pandemic, many Starbucks employees said, is that they became incredibly close with their coworkers. That’s partly to do with the physical locations Starbucks occupies. Starbucks stores are tight spaces, where workers bump into and talk to each other constantly — valuable circumstances when trying to unionize. (Situations like this are also less likely at workplaces like giant Amazon warehouses.)

In general, the Starbucks union efforts have been very grassroots, driven by the front-line workers themselves. Starbucks employees at unionized locations are the ones bargaining for a contract with company lawyers — not a union rep. While union members typically work with their representatives to decide what they want in their contract, the negotiations themselves are usually left to the union and their lawyers.

“There’s nobody top-down making a decision about which stores should organize or go public. It depends on the workers in each store,” Givan, the Rutgers professor, said. “I think that’s crucial.”

This grassroots movement has even drawn support from Starbucks’s shareholders. Recently, investors representing $3.4 trillion in assets under management asked the company to remain neutral and “swiftly reach fair and timely collective bargains,” should more Starbucks stores vote to unionize.

The challenges ahead

Unionizing in America today is not easy — that’s part of what makes the Starbucks workers’ success so impressive. But experts aren’t sure the extent to which that success could be replicated at other food and beverage chains or in other industries. Despite organizing in new industries like food service and digital media in recent years, union membership overall is still in decline.

Givan said the easiest way forward for the labor movement might be through other progressive brands — especially ones where workers feel the company hasn’t lived up to that progressive ethos. For example, workers at a Manhattan REI store, an outdoor equipment retailer that puts “purpose before profits,” voted to unionize in March, saying the company failed to prioritize their safety. REI employees accused the company of union busting, by spreading misinformation about the unions, holding captive audience meetings, and withholding promotions.

The road might be tougher at more iron-fisted companies like Amazon. Ahead of the first union vote at an Alabama warehouse, the company had mailboxes installed on its grounds, giving workers the impression that the company was monitoring its union votes. In Staten Island, the company fired a warehouse supervisor named Chris Smalls the same day he participated in a protest about unsafe conditions during the pandemic. (Smalls went on to create the Amazon Labor Union which led the successful union drive at the Staten Island warehouse.)

Starbucks has also been aggressively fighting the union. The company’s resistance is very apparent to its workers who are organizing. A number of workers told us that they’d been fired or had their hours severely cut back over their association with the union. Workers United has filed nearly 70 unfair labor practices against Starbucks. The NLRB recently dinged the company over more aggressive tactics like illegally penalizing organizers, by suspending an employee and denying another’s scheduling preferences, over their union support. Starbucks fired seven unionizing workers in Memphis after hosting a TV interview about them organizing at the store, but said they were let go for reasons outside the union. Starbucks called any allegations of union busting or firing people over unionizing “categorically false.”

“From the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we are better together as partners, without a union between us, and that conviction has not changed,” Starbucks said in a statement to Recode.

Union organizing is also difficult for reasons beyond pushback from management, including a long and arduous process and labor policy that doesn’t favor workers. And faced with those hurdles, plenty of workers decide to advocate for themselves in other ways, without formally organizing, according to Erica Smiley and Sarita Gupta, authors of The Future We Need: Organizing for a Better Democracy in the Twenty-First Century. According to Smiley and Gupta, there’s also been an increase in so-called worker standards boards, in which groups of workers take part in decisions and rule-making alongside politicians and employers in a non-union setting. State and local governments have formed standards boards in the past few years to guide everything from compensation to safety.

Fight for $15 and a Union, which is a broader advocacy movement rather than a union, has helped gain benefits and raise the minimum wage for millions of workers in cities and states around the country. Angelica Hernandez, a McDonald’s worker in California who has been working with Fight for $15, went on strike early in March 2020 to protest the unsafe working conditions at her job. She’s not part of a union, but simply walked off the job with a couple of colleagues, and it worked. Thanks to this walkout, she got PPE, sanitizer, and temperature checks at work for her and her colleagues.

Going on strike is risky, and many people can’t afford to lose that pay. That’s why Hernandez is hoping California passes AB 257. The first-of-its-kind bill would standardize wages, hours, and conditions for all fast food workers and cover half a million employees at places like Starbucks and McDonald’s, not just unionized ones.

“We’re all suffering across the board with things like sexual abuse and labor abuse,” Hernandez told Recode through a Fight for $15 translator. “That’s why it’s important for us that it’s not just one or two restaurants, but that all fast food workers have protections.”

The increased propensity for workers to quit and find new jobs in the current tight labor market is another way employees are improving their situation outside unions. Smiley considers the Great Resignation to be a form of worker action, like a strike. “You can’t deny the implications it’s had on the labor force and on labor economics,” she said, referring to how, among other benefits, increased rates of quitting have driven up wages, especially in the lowest-paying sectors.

On a national level, Democrats have put forth a labor bill known as the PRO Act that would make it easier for workers to organize, but it has stalled in the Senate. Perhaps a more promising route is through the NLRB. Jennifer Abruzzo, who was confirmed by the senate as the NLRB’s general counsel last year, told More Perfect Union that she wants to make it harder for employers to intimidate workers who want to unionize. She’s asking the organization to reconsider the Joy Silk Doctrine, which would mean that employers would have to recognize a union based on simple majority support.

All things considered, it’s remarkable that a growing number of Starbucks workers are unionizing right now. And because more locations start their own drives after each new union victory, it’s not hard to imagine as many as 50 unionized Starbucks stores by this summer.