Same-day delivery of millions of products. Answers to your every question by simply calling out, “Alexa.”

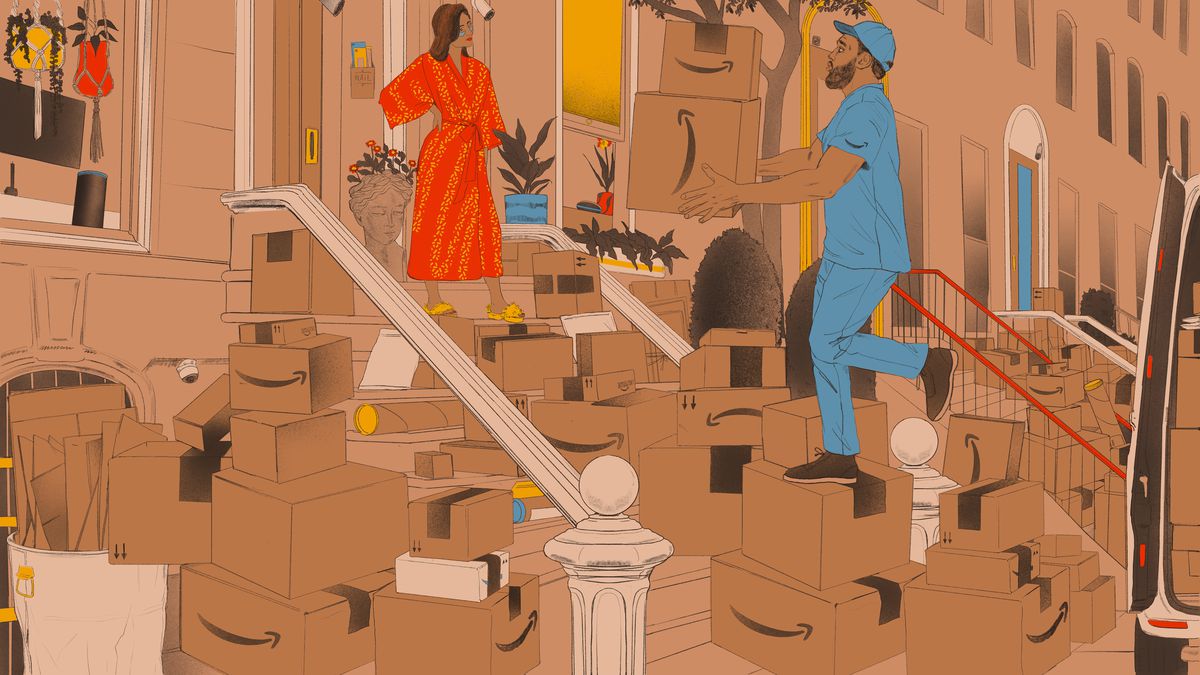

Amazon has transformed our expectations for how we buy things and how we interact with technology. It’s now intuitive for many of us to buy almost anything we want with a click — whether from Amazon or some other retailer — and to count on it being delivered within days, if not the same day. As Amazon has built the sprawling logistics and delivery empire that makes this possible, it has also begun to change the working lives of many Americans — in some ways for the better, and in some ways for the worse.

That shift is most clear in its own workforce: More than 1.1 million people now work directly for Amazon in the US, with some in its offices and the majority in its ever-expanding network of more than 800 warehouse facilities in North America alone. At its current hiring rate, Amazon will overtake Walmart as the largest private-sector employer in the US in the next few years — meaning about 1 percent of US workers will be employed directly by the tech giant.

However, its influence extends far beyond its actual employees, reaching a workforce employed by companies partnering and competing with Amazon. Some, such as Amazon delivery drivers in Amazon-branded vans and trucks, work for third-party companies that sign exclusive contracts with Amazon and are managed by Amazon technology and expectations. Others work for Amazon competitors, big and small, who are striving to keep up with the tech giant by expanding their e-commerce offerings and by imitating its business and employment practices. This shift is only in the early stages, but the ripple effects of Amazon’s influence as an employer will spread over time across the retail, e-commerce, and delivery industries.

“Anyone who wants to do business with Amazon has to conform,” said Rebecca Givan, a labor professor at Rutgers University. “And anyone who wants to compete — that’s kind of everyone — [has] to keep up with what they are doing with productivity, which seems to necessitate massive surveillance.”

Amazon’s workplace culture has long centered on “customer obsession” — doing everything and anything to satisfy customers. That mission has led Amazon to become a force of convenience the world has never seen before. Over the last decade, Amazon has outfitted its warehouses with robots, performance-tracking software, and reengineered workflows, all in the name of pushing the limits on what Amazon can offer its customers, and how quickly.

These innovations have created labor issues, including comparatively high injury and worker churn rates, turning a great American innovation story into a complex evaluation of what it takes to get what we want when we want it — and whether we should expect more from a company that’s setting the bar for what many American employers expect from workers.

To understand the potential consequences of what Amazon has built since its humble beginning as an online bookseller, it’s important to first understand how extraordinary its transformation has been.

This evolution was led early on by Jeff Wilke, a former manufacturing executive who joined Amazon in 1999 and eventually rose to the No. 2 position in the company as CEO of its core e-commerce business globally. Wilke set out to overhaul the layouts of Amazon warehouses and the software powering their processes in order to speed up shipping times and make more accurate promises to customers. To do this, Wilke and his team incorporated techniques he learned studying the lean manufacturing methodology, which aimed to maximize worker productivity while minimizing unnecessary steps. The warehouse work Wilke oversaw eventually led company founder and former CEO Jeff Bezos to feel confident in launching Amazon Prime and its two-day delivery promise.

In those early years, as Amazon began to expand beyond selling books, one of the most common criticisms of work in its facilities was how much walking workers had to do — as much as 12 to 15 miles a day for some roles. That changed when Amazon started adding warehouse robots to its facilities after acquiring a startup called Kiva Systems in 2012. In warehouses with robots, workers no longer had to traverse endless aisles of merchandise all day; instead, Kiva’s robots carried portable shelves to them at stationary stations. The robots’ arrival also boosted worker productivity, which was the main goal — essentially turning the Amazon warehouse into the 21st-century version of a manufacturing assembly line, one where the goal is assembling e-commerce customer orders.

Eventually, labor historians say, Amazon’s warehouse environment began resembling a blend of at least two different manufacturing approaches pioneered in the early 20th century. One is Taylorism, a dehumanizing system for factory work invented by the mechanical engineer Frederick Taylor. Taylorism, or “scientific management,” broke complex manufacturing down into limited, repetitive tasks; managers were the experts responsible for coming up with the best way to accomplish those tasks, and workers were treated like simpletons. “Amazon is an example of a company which is ultra-Taylorized,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy at the University of California Santa Barbara.

The other approach involved the moving assembly line innovation pioneered by Henry Ford’s automobile factories. However, this innovation increased the monotony of the job and the pace in Ford’s factories. Workplace churn increased. And in 1914, Ford was compelled to nearly double a day’s wages to $5 in an attempt to stabilize the workforce. Similarly, at Amazon, company leaders increased the hourly wage minimum to $15 in 2018, amid significant external pressure led by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT). That move led retailers like Walmart and Target to raise their wages too.

Amazon spokesperson Richard Rocha opposed comparisons between the company’s working conditions and the harsh factory work of past centuries. He said Amazon has been investing heavily in safety initiatives, pointing to a company report published in January that said Amazon spent $300 million on safety initiatives in 2021 alone, and employs nearly 8,000 safety employees worldwide. The report also argues that robots reduce the physical demands on workers because they reduce the amount of walking previously necessary in key roles.

Unsurprisingly, the mind-boggling pace of production that Amazon has pioneered is the envy of, and inspiration for, Amazon’s business partners and competitors. As they try to keep up with Amazon, many of them are starting to emulate its business practices, workplace culture, or labor standards.

An early example of this traces back to around 2012, when Amazon began overhauling its fulfillment centers by installing robots. Suddenly, investors began pouring money into robotics. Investments in startups that make warehouse and factory robots increased from $300 million in 2015 to a startling $1.9 billion in 2020. Along the way, Amazon competitors have gobbled up some of these robotics companies to try to keep up. In 2019, the e-commerce software company Shopify spent $450 million to purchase a company called 6 River Systems, which makes mobile robots used in e-commerce warehouses that offer to boost worker productivity by two to three times.

Even some businesses outside of the e-commerce and delivery sectors are taking inspiration from Amazon’s work culture. A cottage industry run by consultants and former Amazon employees has started to spring up in recent years, offering to train other business leaders on the ins and outs of the Amazon Way.

Colin Bryar, a former Amazon executive and the co-author of a book about the secrets to Amazon’s success called Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets From Inside Amazon, told Recode that the consulting firm he founded with his co-author, Bill Carr, works with business leaders and companies from “around the world, in a number of different industries,” to teach them how to create company cultures and management practices similar to Amazon’s.

The small delivery firms that employ these drivers are also often at the mercy of Amazon. The company promises them consistent package volume when they deliver exclusively for Amazon, but it comes with a big caveat: Amazon can end the relationship without having to explain why.

“I fought in Iraq and Afghanistan and being deployed was better than [the anxiety of] working for Amazon,” said Ted Johnson, a military veteran who told Recode in the summer of 2021 that his delivery business handled more than 2 million Amazon deliveries before he had to shut it down when Amazon did not renew his contract and offered no explanation.

Amazon’s influence is evident in its direct competitors, too: In recent years, Amazon’s two largest mass retailer competitors, Walmart and Target, have hired top logistics executives from Amazon to lead their warehouse and shipping strategies, in a clear bid to learn the Amazon Way. And a number of up-and-coming e-commerce sites, including the online pet goods retailer Chewy and apparel platform and retailer Rent the Runway, have done the same.

At Walmart, former employees say that new warehouse leaders hired from Amazon developed a reputation for treating workers more harshly than prior warehouse bosses — but they did, at times, improve productivity.

For many in the business world, that trade-off is worth it because productivity and financial success are main priorities. That’s why Amazon has so many emulators. That’s a good thing, argues Mark Cohen, the director of retail studies at the Columbia Graduate School of Business.

“It would be nice if Amazon and other companies were a tad more empathetic,” he told Recode, “but we should be so lucky to have other Amazons in how successful they’ve been and how much they’ve grown. Amazon is the embodiment of the American success story,” he said.

As more retailers and logistics companies begin to emulate Amazon’s fulfillment and delivery operations, the downsides of Amazon’s success story have some labor experts deeply concerned about the well-being of workers across these industries. “It’s really a race to the bottom,” Givan, the labor professor at Rutgers University, told Recode. She said Amazon is setting a dangerous example for other companies and their employees by how fast it expects its warehouse employees to work and how closely it tracks their every move.

“What I get from talking to Amazon workers … is that the pay is not the worst, especially for non-union workers, and the benefits are okay,” she said. “But the physical demands and the surveillance are grueling and much, much worse than other employers in the same sector.”

One of the most troubling results of Amazon’s labor practices is that its workers have a higher chance of suffering a serious injury on the job than at competitors’ warehouses, according to data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

“In 2020, for every 200,000 hours worked at an Amazon warehouse in the United States — the equivalent of 100 employees working full time for a year — there were 5.9 serious incidents, according to … OSHA data,” the Washington Post reported last year. “That’s nearly double the rate of non-Amazon warehouses. In comparison, Walmart, the largest private US employer and one of Amazon’s competitors, reported 2.5 serious cases per 100 workers at its facilities in 2020.”

And in March of this year, Washington state’s labor department hit Amazon with a $60,000 fine for a “willful violation” of state labor laws, saying “ergonomists found that many Amazon jobs involve repetitive motions, lifting, carrying, twisting, and other physical work … at such a fast pace that it increases the risk of injury.” Amazon is contesting the citation.

In response to a request for comment on the OSHA injury data, Rocha pointed Recode to the safety report Amazon published in January, which states that the company saw a 43 percent improvement from 2019 to 2020 in the rate of worker injuries that necessitated missing work. The report argues that if you compare Amazon injury rates to other large transportation and logistics companies, rather than retail warehouse rivals, “our performance is comparable, and in some cases better.” That comparison, however, would have limitations because no other US company oversees such a massive, complex network of both order fulfillment and delivery.

In the past, Amazon defended its comparatively higher injury rates by arguing that the company is more aggressive than its peers when it comes to documenting injuries. But Ken, a former Amazon employee who worked in first aid and safety roles over four years from 2016 to 2020, told Recode that managers sometimes discouraged him from referring injured workers to external doctors, in part because that could result in the company needing to record the injury with OSHA. (Ken asked not to use his full name out of concern that it could impact his career.) This pressure didn’t come in cases of severely injured employees, Ken said, but rather for “gray area” injuries.

That raised alarms for him. “They basically want you to influence or sell it that, ‘Hey, we can treat you here, we can do follow-ups here, we can keep icing your ankle,’” said Ken, who was a paramedic and firefighter before joining Amazon. “If [a doctor gives them] any job restriction or prescription or physical therapy, it’s gonna be an OSHA-reportable event.”

During weeks where he referred an above-average number of employees to outside doctors, Ken said he would hear about it from a manager.

“You were gonna get some heat and you were gonna get interrogated,” he told Recode.

Amazon’s spokesperson said the company had no record of this employee raising concerns, and that warehouse workers are free to seek care outside of work. Rocha also said that the company’s onsite medical representatives have guidelines on what type of injuries should be treated in-house versus at an outside facility, and disputed the claim that care and treatment are determined by what is or isn’t reportable to OSHA.

Instead, he said Amazon was working on a variety of solutions in tandem, including “rotational programs that help employees avoid spending too much time doing the same repetitive motions.” The company has said in a safety report that a pilot test of the rotation program reduced certain types of injuries from repetitive motions by more than 40 percent.

Perhaps, under Jassy’s leadership, Amazon will find ways to reduce injuries that will become a model for other companies that already emulate more customer-focused traits of Amazon’s labor practices. But, in a capitalist society like the US, Amazon’s investors mainly judge its success on different metrics: sales growth and profits. As long as its employee injury rates don’t dramatically alter those metrics for the worse, it’s fair to be skeptical that the company will altogether prioritize injury reduction over the productivity that has made Amazon one of the biggest business disruptors in decades. How this push-and-pull plays out may very well determine how seriously Amazon’s followers prioritize the well-being of their workforces as they try to compete and satisfy their customers’ demands for speed and convenience.

The other key aspect of Amazon’s workplace that labor experts are worried about is how quickly it loses and replaces its employees — a problematic quality for a labor leader to have.

Even before the pandemic, the company’s turnover rate at times reached 150 percent, according to the New York Times — and that was a feature of the company’s employment system, not a flaw.

When Amazon talks about its workplace in hiring settings, it uses the tagline: “Come Build the Future with Us.” But many Amazon workers don’t last long enough at the company to enjoy the spoils of the future. And the precedent the company is setting for its emulators is something to pay attention to.

It is true that Amazon’s starting pay is often higher than what comparable jobs will pay workers. Amazon’s leaders often respond to critics of its labor practices by pointing to wage increases for new hires in recent years, as well as the fact that it offers employees medical insurance benefits starting on their first day on the job — which isn’t always the case at other companies.

Company officials also nod to how influential Amazon is, saying that the company’s pay minimum sets expectations for the broader industry that other big companies eventually copy. A recent study published by researchers at the University of California Berkeley and Brandeis University gives their point some credence; it found that Amazon wage increases in recent years have led to rising pay for workers employed by other companies near Amazon facilities. But the relatively higher pay and superior benefits don’t matter much for all the Amazon workers who leave the company after a short time, without having a real opportunity to climb the ladder and build better lives for themselves.

The Amazon spokesperson pointed Recode to a statement Amazon has previously used to discuss its workplace turnover, which says that many hires at Amazon are rehires, though the company declined to reveal the exact percentage. “We’re proud to create both short-term and long-term jobs with great pay and great benefits,” the statement adds. “Some employees stay with us throughout the year and others choose to only work with us for a few months to make some extra income when they need it.”

“A lot of companies, and Amazon would be one of them historically, have kind of accepted eye-watering levels of turnover as just Newtonian physics — an act of God,” Joseph Fuller, a professor at Harvard Business School and the co-director of the school’s Managing the Future of Work initiative, told Recode.

Fuller’s research included a 2020 survey of working people in the US in low-wage jobs, as well as people who have risen out of low-wage jobs. The survey found that most low-wage workers would rather remain at their current companies than jump around for an extra 10 cents an hour or a slightly shorter commute. And the keys to keeping these workers in place revolve much less around entry-level hourly pay than they do opportunities to progress internally, as well as managers who show interest in a worker’s success and connect them with programs that may help them move up.

Fuller said his research doesn’t suggest that companies need to focus on turning every front-line worker into a career employee. For companies like Amazon with more than a million employees in the US alone, that just wouldn’t be feasible. But by investing money and time into building a ladder to more senior jobs, Fuller believes that companies like Amazon can extend an average worker’s tenure from a few months to potentially a few years, which helps the company by reducing the costs of hiring while promoting another American out of the low-wage job trap. Since other employers large and small already emulate Amazon’s existing management and labor practices, such a move could have considerable ripple effects for workers across the US economy.

Amazon has long heralded its Career Choice program, which currently will pay up to $5,250 a year for full-time warehouse employees, and $2,625 for part-time employees, toward tuition, books, and fees at partnering colleges and trade schools. Amazon also announced in 2019 a broader commitment to provide free “upskilling” training to 100,000 employees, including warehouse workers, by the end of 2025. It will take years to judge the effectiveness of such a program.

In the meantime, Amazon workers are trying to change the company from the inside. In April, an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York, became the first in the US to successfully vote to unionize. The Amazon Labor Union organizers, who are all current or former Amazon employees, want to push Amazon leadership in contract negotiations for large hourly raises, longer breaks for workers, and union representation during all disciplinary meetings to prevent unjust firings that may exacerbate staff turnover.

The winning vote was just a first step, as Amazon indicated in an April 7 filing that it plans to file objections to the vote. Either way, the union’s success in Staten Island will likely inspire other workers, both inside and outside of Amazon, to attempt to organize their own workplaces. Already, a vote is scheduled at another Staten Island warehouse beginning April 25, and the results of a union election in Bessemer, Alabama, currently too close to call, are pending a hearing to scrutinize hundreds of contested ballots.

The pressure from the union drives seemed to have forced Jeff Bezos himself to reconsider the company’s treatment of its workforce. In his final shareholder letter as CEO in 2021, he said his company needs “to do a better job for our employees.” His new mission for the tech giant: “Earth’s Best Employer and Earth’s Safest Place to Work.”

“On the details, we at Amazon are always flexible, but on matters of vision we are stubborn and relentless,” he wrote. “We have never failed when we set our minds to something, and we’re not going to fail at this either.”

The stakes couldn’t be higher. If history is any indication, Amazon’s business lines will continue to grow, its warehouse footprint will continue to expand, and so too will its powerful impact on the lives of workers — its own as well as those employed by partners and competitors.

Jason Del Rey is a senior correspondent at Recode by Vox, where he has covered Amazon for the past nine years. He’s also the host of the podcast Land of the Giants: The Rise of Amazon and is writing a book about the Amazon/Walmart rivalry that will be published by Harper Business in 2023.