The Supreme Court handed down a brief order on Tuesday blocking a Texas law that would have effectively seized control over the entire content moderation process at major social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

The Texas law imposed such burdensome requirements on these sites, including disclosure requirements that may literally be impossible to comply with, that it presented an existential threat to the entire social media industry. Facebook, for example, removes billions of pieces of content from its website every year. The Texas law would require Facebook to publish a written explanation of each of these decisions.

At the very least, the law would have prevented major social media sites from engaging in the most basic forms of content moderation — such as suppressing posts by literal Nazis who advocate for mass genocide, or banning people who stalk and harass their former romantic partners.

The vote in Netchoice v. Paxton was 5-4, although it is likely that Justice Elena Kagan voted with the dissent for procedural reasons unrelated to the merits of the case.

The law effectively forbids the major social media sites from banning a user, from regulating or restricting a user’s content, or even from altering the algorithms that surface content to other users because of a user’s “viewpoint.”

In practice, this rule would make content moderation impossible. Suppose, for example, that a Twitter user named @HitlerWasRight sent a tweet calling for the systematic execution of all Jewish people. Under Texas’s law, Twitter could not delete this tweet, or ban this user, if it did not do the same to any user who took the opposite viewpoint — that is, that Jews should be allowed to continue living.

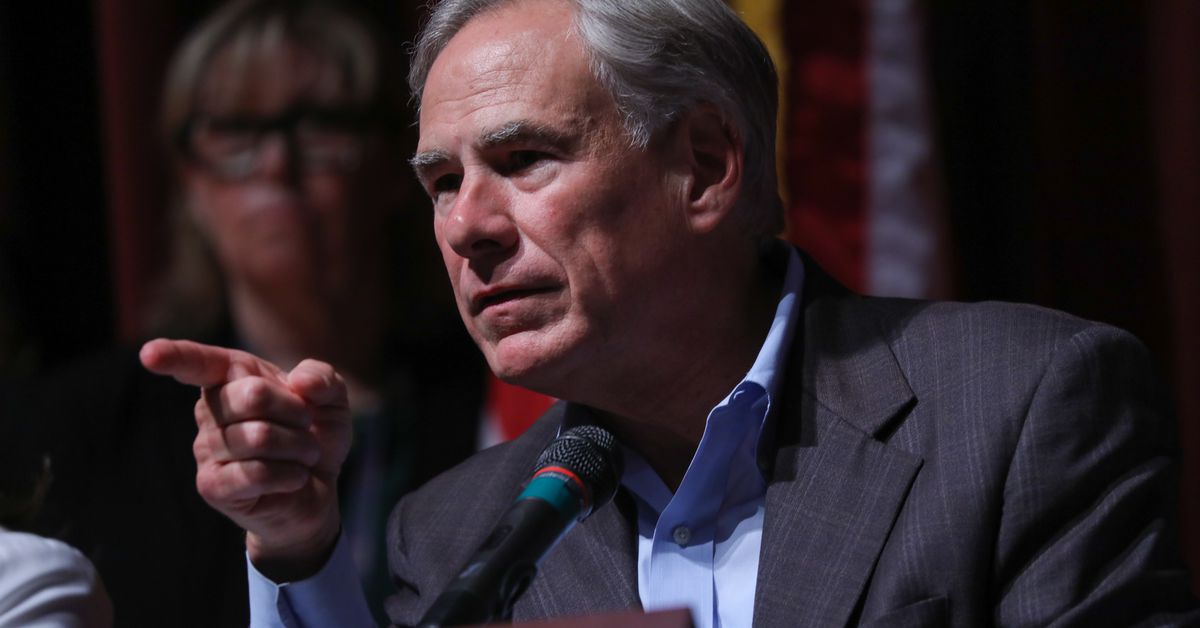

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) claimed, when he signed the law, that he did so to thwart a “dangerous movement by social media companies to silence conservative viewpoints and ideas.” The evidence that social media companies target conservatives in any systematic way is quite thin, although a few high-profile Republicans such as former President Donald Trump have been banned from some platforms — Trump was banned by Twitter and Facebook after he seemed to encourage the January 6 attack on the US Capitol.

The Court didn’t explain its reasoning, which is common when it is asked to temporarily block a law. And Tuesday’s order is only temporary — the Court will likely need to hand down a definitive ruling on the fate of Texas’s law at a future date.

But the majority’s decision is consistent with existing law.

With rare exceptions, it is well established that the First Amendment does not permit the government to force a media company — or anyone else, for that matter — to publish content that they do not wish to publish. As recently as the Court’s 2019 decision in Manhattan Community Access Corp. v. Halleck, the Court reaffirmed that “when a private entity provides a forum for speech,” it may “exercise editorial discretion over the speech and speakers in the forum.”

Although the idea that a corporation such as Twitter or Facebook has First Amendment rights has been criticized from the left following the Supreme Court’s campaign finance decision in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), the rule that corporations have free speech protections long predates Citizens United. Newspapers, book publishers, and other such media corporations have long been allowed to assert their First Amendment rights in court.

The most surprising thing about Tuesday’s order is that Kagan, a liberal appointed by President Barack Obama, dissented from the Court’s order suspending the Texas law.

Though Kagan did not explain why she dissented, she is an outspoken critic of the Court’s increasingly frequent practice of deciding major cases on its “shadow docket,” an expedited process where cases are decided without full briefing and oral argument. Netchoice arose on the Court’s shadow docket, so it is possible that Kagan dissented in order to remain consistent with her previous criticism of that docket.

Meanwhile, the Court’s three most conservative justices, Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch, all joined a dissent by Alito that would have left the Texas law in place.

Alito’s dissent suggests that two narrow exceptions to the First Amendment should be broadened significantly

Alito claimed that the question of whether a state government can effectively seize control of a social media company’s content moderation is unsettled, pointing to two cases that created narrow exceptions to the general rule that the government cannot require a business to host speech it does not wish to host.

The first, Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins (1980), upheld a California law that required shopping centers that are open to the public to permit individuals to collect signatures for a petition on the shopping center’s property. The second, Turner Broadcasting v. FCC (1994), upheld a federal law requiring cable companies to carry local broadcast TV stations.

But, to the extent that Pruneyard could be read to permit Texas’s law, the Court has repudiated that reading of the decision. In PG&E v. Public Utilities Commission (1986), four justices declared that Pruneyard “does not undercut the proposition that forced associations that burden protected speech are impermissible.” So a social media company may refuse to associate with a user who posts offensive content.

Meanwhile, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote that Pruneyard should only apply when a law is minimally “intrusive” upon a business — a standard met by allowing a petitioner to collect signatures on your property, and not by the Texas law, which would fundamentally alter social media companies’ business operations and prevent them from suppressing the most offensive content.

Similarly, the Turner case held that cable companies are subject to greater regulation than most media companies because they often have exclusive physical control over the cables that bring television stations into individual homes. This is not true about social media websites. While some social media platforms may enjoy market dominance, they do not have physical control over the infrastructure that brings the internet into people’s homes and offices.

The Supreme Court case governing how the First Amendment applies to the internet is Reno v. ACLU (1997), which held that “our cases provide no basis for qualifying the level of First Amendment scrutiny that should be applied to” the internet.

Had Alito’s approach prevailed, the Texas law most likely would have turned every major social media platform into 4chan, a toxic dump of racial slurs, misogyny, and targeted harassment that the platforms would be powerless to control. It also could have placed every social media company at the whims of the 50 states, which might impose 50 different content moderation regimes. What is Twitter or Facebook supposed to do, after all, if California, Nebraska, or Wyoming passes a social media regulation that contradicts the law enacted by Texas?

For the moment, that outcome is averted. But, because Netchoice arrived on the Court’s shadow docket, and because a majority of the Court resolved this case in a brief order without any explanation of its reasoning, the question of whether the First Amendment permits the government to regulate social media moderation technically remains open — although the fact that a majority of the Court stepped in to block this law bodes well for the social media industry as its challenge to the Texas law proceeds.

The Court’s order in Netchoice is temporary. It preserves the status quo until the Court can issue a final ruling on how the First Amendment applies to social media.

But it is unlikely that this issue will remain open very long. Two federal appeals courts have reached contradictory rulings on the legality of Texas-style laws. So the Supreme Court will need to step in soon to resolve that conflict.