JBS Foods, the world’s largest meat supplier and a recent ransomware victim, revealed on June 9 that it paid $11 million to hackers. The chief executive of the company’s United States division, Andre Nogueira, said it was a deal to prevent future attacks.

Nogueira told the Wall Street Journal that making the payment was a “very painful” but necessary decision — even though the company was able to restore most of its systems from its own backups. The payments were made in bitcoin, as is typically the case in these attacks. The revelation comes after the CEO of Colonial Pipeline, which was attacked weeks earlier, admitted to paying roughly $4.5 million in ransom and as a spate of high-profile ransomware attacks have disrupted the gas, transportation, and insurance sectors.

You may not have heard of JBS Foods before, but depending on your dietary restrictions, you’ve probably eaten the world’s largest meat supplier’s wares. On May 31, the company revealed it was hit the day before by what it called an “organized cybersecurity attack” on its North American and Australian systems, and it was in the process of restoring them with backups. JBS said on June 3 that it had fully restored global operations, avoiding a prolonged shutdown that could have affected meat prices given JBS’s dominance in the industry.

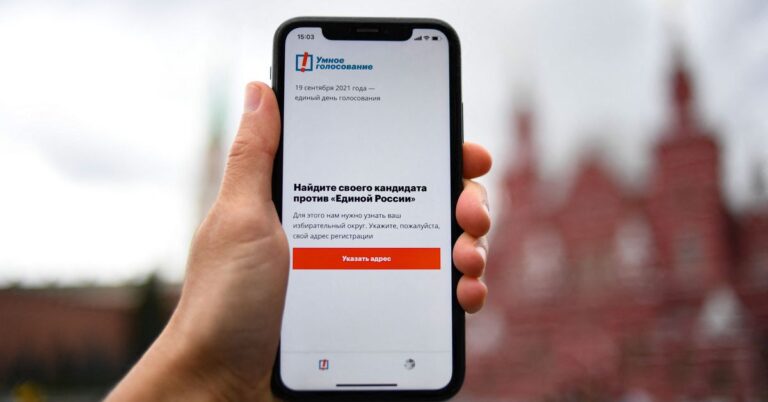

JBS didn’t admit that the cyberattack was ransomware until June 9, but the White House said on June 1 that the attack was indeed ransomware. The FBI announced the following day that the attack likely came from a hacker organization known as REvil or Sodinokibi, which is believed to be based in Russia.

Ransomware is malware that encrypts its target’s systems. The hackers then demand a ransom to unlock the files. In some cases, the hack also gains access to the target’s data, and the ransom will also guarantee it won’t be made public. JBS said it did not believe any of its data was compromised in the attack.

“Attackers are operating like a well-oiled business industry, yielding high profits in a year that most businesses struggled,” said Nick Rossmann, global lead for threat intelligence at IBM Security X-Force. “Why? The new ransomware business model is relentless, extortive, and paying off.”

The attack forced JBS to close all of its beef plants in the United States temporarily, according to Bloomberg. One of its Canadian plants was also affected, and the company paused beef and lamb kills in Australia, presumably until the plants needed to process that meat were back online.

The attack mirrored the Colonial Pipeline shutdown in May. Colonial, which supplies the East Coast of the United States with nearly half its fuel, was shut down for several days when a ransomware attack locked up some of its systems. The pipeline itself wasn’t affected, but the company took it offline as a precautionary measure. The shutdown caused gas shortages and price increases in some states, although those were likely from panic buying in anticipation of shortages rather than actual shortages.

The pipeline was back online in less than a week, and the company admitted to paying a ransom of about $4.4 million in bitcoin. An enterprising criminal group called DarkSide, which offers a sort of “ransomware as a service” business model, was behind the attack, though the group that contracted DarkSide’s services has not yet been identified. DarkSide itself appears to have gone dark in the fallout from the attack. REvil’s business model is thought to be very similar to DarkSide’s.

“Hackers are going after bigger and more high-profile targets because they know they can be successful,” Ekram Ahmed, a spokesperson for cybersecurity company Check Point Software Technologies, told Recode. “When there are headlines out there that the Colonial Pipeline actually paid $4.4 million in ransom, the ransomware business attracts new entrants. We can expect things to get worse, and I firmly believe ransomware is now a full-blown national security threat.”

Deputy National Security Advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technology Anne Neuberger sent a letter to corporations on June 3, urging them to take “critical steps” to protect themselves from threats that she described as “serious” and “increasing.” And the Department of Justice is reportedly stepping up its response to the ransomware threat with a new Ransomware and Digital Extortion Task Force, which was announced in April and credited with recovering much of the ransom Colonial paid in June.

Yet these developments still signal a troubling trend in ransomware attacks, especially those that could cause massive disruptions. Ransomware attacks have become increasingly common, though hackers usually go for smaller, more vulnerable targets that are likelier to have poor cybersecurity and pay the ransom to get their systems back online as quickly as possible. Cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, have made it much easier for hackers to receive ransoms. And, as DarkSide shows, hackers have become much more organized in their efforts.

“Ransomware is big business right now,” Ahmed said. “We’re seeing a staggering 102 percent overall increase in the number of organizations affected by ransomware this year, compared to the beginning of 2020.”

The average cost of recovering from a ransomware attack appears to have doubled as well, according to a recent report from cybersecurity firm Sophos, and is higher than the ransom itself. One company, Chainalysis, determined that $350 million was spent on ransomware payments in 2020. But it can be hard to know the full scale of attacks and ransoms paid because many companies don’t report them in the first place. CNA Financial Corporation, one of the largest insurance companies in the United States, paid $40 million in ransom last March, which was only revealed two months later when it was leaked to Bloomberg.

When the victim is a massive company that is a crucial part of a supply chain, however, attacks can’t be covered up so easily. It seems that hacking groups aren’t worried about getting caught, are becoming more brazen, and are going after bigger fish — or, in the case of JBS, cows.