Since the early 20th century, the US has been a world leader in innovation and technical progress. In recent decades, however, some experts have worried that the country’s performance on these fronts has been slowing, even stalling.

There are many possible explanations for this phenomenon, but one has seemed especially salient in recent years: an immigration system that discourages, and often turns away, the most highly skilled and talented foreign workers.

Historically, immigrants have played a vital role in American innovation. As Jeremy Neufeld, an immigration policy fellow with the Institute for Progress, a new innovation-focused think tank, remarked to me, “It’s always been the case that immigrants have been a secret ingredient in US dynamism.” Robert Krol, a professor of economics with California State University Northridge, describes it this way: “The bottom line is that when you look at the impact of immigrants — whether you think about starting businesses or innovating patents — they have a large, significant impact.”

Multiple analyses of historical immigration patterns show that more migrants to a region correlates with a higher rate of innovation and related economic growth. By contrast, when immigration is more restricted, companies — especially tech companies and those that conduct innovative R&D work — are less successful, and growth in jobs and wages slows. Studies have also shown that immigrants tend to be entrepreneurial: Based on survey data between 2008 and 2012, 25 percent of companies across the US were founded by first-generation immigrants. Other research shows that immigrants are more likely than native-born US citizens to register patents.

As Neufeld points out, the Covid-19 pandemic might have gone much worse if immigration had always been as restrictive as it is now. A number of co-founders and critical researchers with Moderna are immigrants, as is Katalin Karikó, a pioneer of mRNA research — who, if she had tried to immigrate after the 1990 H-1B reforms to the skilled guest worker program, might not have been able to come to the US at all.

Those H-1B guest visas are at the center of the issue today, some experts say. Designed in 1990 to bring in skilled professionals to meet labor market shortages, visas through the H-1B guest workers program are sponsored by employers, who submit petitions to bring in particular foreign professionals appropriately qualified for specific, highly skilled roles. Guest workers generally need at least a bachelor’s degree in a relevant field.

According to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), there are about 580,000 foreign workers currently on H-1B visas, a small percentage of the US workforce and immigrant population. But they are disproportionately concentrated in STEM, particularly computer-related occupations, often in fields where cutting-edge technologies are being developed.

Unfortunately, the H-1B process is falling increasingly out of date and badly failing to serve its original purpose of turning on the talent tap for top innovative companies. Congress sets an annual cap on how many H-1B visa holders can come in, and that cap is now far below what the labor market demands. The crush of applications once the window opens for a given year on March 1 is so intense that, in every year since 2014, USCIS has resorted to a lottery system instead of a first-come, first-serve process. That means that year in and year out, hundreds of thousands of high-skilled workers from abroad try to come to the US and ultimately fail, so that both the prospective employee and the company hoping to hire them end up losing out on their preferred option.

That shortfall is a policy problem. The US has long been a desirable destination for young, highly educated foreign workers eager to seek out the best career opportunities. Facing a longstanding shortage of skilled STEM workers, US companies and the overall US economy stand to benefit. But the country risks losing its position to others like the UK or Canada, which have made recent immigration reforms aimed at attracting and retaining high-skilled young people, if the US continues to restrict skilled immigration so heavily.

As with many policy problems, there are some nuances here to pay attention to, not least the potential effect any policy changes might have on native-born US workers. And this discussion doesn’t touch on the debate over lower-skill guest workers vital to the US economy and the policies surrounding them. (That’s related, but beyond the scope of this story.) But there is little doubt that from the perspective of speeding innovation, the US system needs fixing.

“The big picture is that our ability to recruit talent is directly related to our economic success as a country,” economist David Bier, associate director of immigration studies with the libertarian Cato Institute, told me. “We don’t know which [immigrant] is going to have the brilliant insight that totally transforms the economy over the next 20-30 years.”

Why the H-1B system is failing

Table of Contents

The H-1B visa is a three-year temporary work visa that is generally renewable once for three years. It’s not in itself a path toward permanent residency. (H-1B holders, however, can begin the process of getting a green card to stay in the US for good while already in the country as a guest worker.)

Currently, the annual cap is set at 65,000 visas, with an additional 20,000 slots allocated for workers with graduate degrees from US universities. That’s significantly down from the cap set in the early 2000s of 195,000 annually.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, USCIS accepted petitions on a first-come, first-serve basis until the annual cap was met. In most years, when the total applications eventually maxed out the cap, it inevitably left out many highly valuable potential immigrants or delayed their visa by a year, but at least the process allowed companies some opportunity to prioritize applying earlier in the annual window for employees they saw as more critical.

In 2014, the annual H-1B applications began spiking and the volume of applications received just in the first few days of the window prompted USCIS to switch to a lottery system. For fiscal year 2023, only 26 percent of the 483,000 applications received — more than double the 201,000 petitions submitted for 2020 — were chosen for processing.

That level of restriction has hit the computer and software sector the hardest. The US has faced a shortage of qualified experts in computer-related occupations since the beginning of the H-1B program. Despite heavy investment in STEM programs at US universities, many companies claim they struggle to meet their hiring needs, especially in computer-related specialties; as a result, software engineers and programmers from overseas are in high demand by American companies.

A study by the National Foundation for American Policy, a nonprofit that carries out public policy research on trade and immigration, found that between 2005 and 2018, more than half of all H-1B visas were granted to workers in computer-related occupations, even though the field represents barely more than 5 percent of the total workforce. Economist Gordon Hanson finds that foreign-born workers represent 55 percent of the job growth in AI-related work — a small subset of total jobs in computer-related occupations, but an area with rapid innovation — since 2000.

Other STEM fields are also affected by the H-1B crunch. Biology and engineering, as well as teachers in higher education, are overrepresented in H-1B applications. It seems likely that many of these workers’ petitions are losing out in the lottery, pushed out by the huge numbers of IT-related applications.

One more problem afflicts the system. The H-1B program was originally envisioned as a short-term guest worker program, and the many skilled foreign professionals who want to permanently migrate and settle in the US were supposed to transition onto an immigrant visa offering a route to permanent residency — usually one of the employment-based visas — as their next option.

However, a lengthy backlog in the employer-sponsored green card pipeline — caused by the fact that new annual applications have exceeded slots for some time — means that approximately 1.4 million H-1B workers are currently waiting in line to apply for permanent residency, even as their visas are tied to their current employer. In tech fields, it’s common for employees to change jobs as they seek out the best opportunities, so the current system can severely limit a worker’s economic and career prospects.

As Bier puts it, “People get trapped in these wage tiers that are not appropriate for their skill set because ultimately the green card backlog decides whether they get a promotion or whether they can move to another company.”

For Indian guest workers, the current backlog is up to 90 years, and an estimated 200,000 children of immigrants waiting in the permanent residency pipeline face the threat that they will age out of their family-based eligibility when they turn 21, leaving them with no route to legally stay in the country. Bier’s analysis estimates that 215,000 petitions will expire with the applicant’s death before ever being processed.

The downsides of the H-1B system

One unintended consequence of the current H-1B system that experts have flagged is the massive success of a particular business model: offshore “outsourcing” companies, mainly based in India. Outsourcing companies can put in thousands of H-1B petitions for workers they consider interchangeable, mainly junior programmers, and profit by sending the applicants who win the lottery to work for US-based companies as agency contractors.

This model is popular enough that outsourcing companies make up a substantial percentage of all H-1B petitions filed. According to Ron Hira, a research associate with the progressive Economic Policy Institute (EPI), 17 of the top 30 companies by annual H-1B applications are outsourcing firms.

There are several ways this could harm US workers, US companies, or innovation overall. One concern is that the “outsourcing” firms hold enormous leverage over their employees, effectively having a monopoly on their employment, and could thus exploit and underpay them, potentially undercutting US workers’ salaries.

There is an ongoing debate about whether this is happening. According to EPI, the local median wage for an occupation should be a minimum bound for H-1B workers, and with two of the wage tiers below the median, companies can use the H-1B for “wage arbitrage” and hire lower-paid foreign employees at the expense of US citizens.

But while there are some high-profile examples of US workers being laid off en masse and replaced by agency workers, a number of different economic data analyses — though certainly not all — show little if any large-scale negative effect on US workers’ job opportunities or wages. A study by the Cato Institute shows that 100 percent of H-1B employers pay at least average market wages, and often more.

As Madeline Zavodny, professor of economics at the University of North Florida, told me, “What you hear often from workers unions and so on is that, in their view, the ready availability of relatively low-wage young immigrant workers coming in on these H-1B visas reduces job opportunities and wages for competing US natives, particularly those who have been in the occupations for a while.” But, she added, “there’s not a whole lot of evidence to back that up.” If, as claimed by many companies and economists, there’s a real shortage of native workers in computer-related occupations, we wouldn’t expect to see much displacement or wage undercutting.

According to a policy brief that Zavodny wrote for the National Foundation for American Policy, wage data collected and analyzed via multiple different methodologies mainly shows the opposite: More foreign guest workers in a given occupation and region tends to result in salaries increasing faster in those places and job classes, likely due to general economic growth and innovation.

Another concern with the current system is that the incentives it has created work against the goal of encouraging innovation. Because outsourcing firms are pouring tens of thousands of applications into the total “pot,” highly innovative US-based companies face lower odds of obtaining an H-1B for a specific employee. Under the system, a world-class expert in a niche field is treated exactly like a newly graduated junior employee, which makes it much harder for companies to bring in those experts who could do the most transformative work, especially when outsourcing firms are putting in thousands of applications annually.

As Francesc Ortega, a professor of economics at Queens College, puts it, “A company could have a wonderful case to make for why they [need] that particular Chinese engineer. Maybe they are about to develop the vaccine that will cure everything, but they need that guy, and everyone looking at the petition would be able to say, ‘Yeah, definitely, these guys should be top priority.’ But that mechanism doesn’t exist.”

Can incremental change fix a broken system?

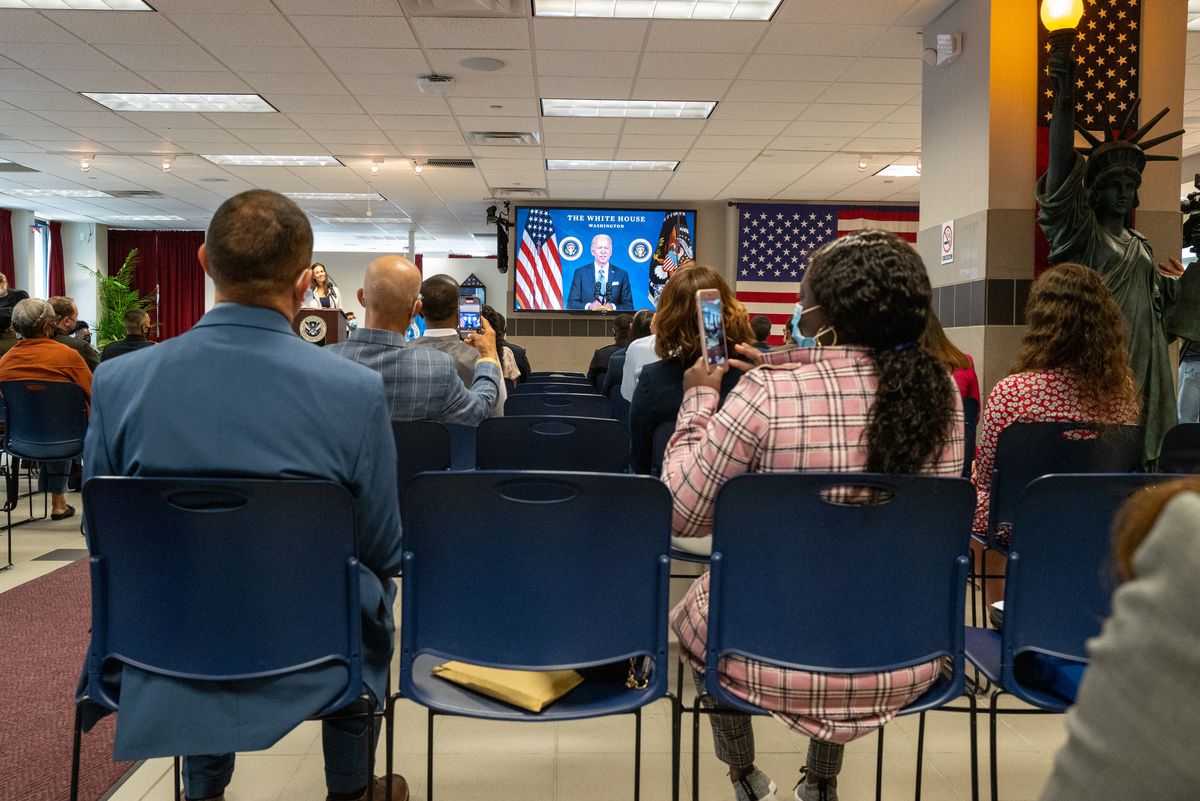

How then to create that mechanism and reconstruct the US’s high-skilled immigration system to bring in the world’s top talent while also minimizing potential harms to US workers? The Biden administration has promised to reform the system, and policy thinkers have proposed solutions, none of them perfect.

One idea came from the Trump administration. In 2020, then-President Trump proposed replacing the lottery with a salary-based ranking system. That is, rather than using a lottery to select candidates, USCIS would rank the petitions based on the salary offered by the employer, and start processing at the highest-salary end until the cap was reached. Such a system would in theory prioritize the most skilled and qualified candidates over the more junior workers. That would help innovative companies bring in the most valuable domain experts who play critical roles in their cutting-edge research, rather than being pushed out by outsourcing companies’ huge numbers of applicants.

However, Zavodny told me she’s concerned this system would disproportionately disadvantage young recent graduates, many of whom are very driven to come to the US. Some other concerns include the fact that pay gaps along racial and gender-based lines are still a problem in the US; a salary-based system could risk disproportionately shutting out those groups affected by salary bias. And as the cost-of-living gap between regions in the US continues to increase, a system that failed to adequately correct for this in the salary ranking might make it difficult for companies in areas with a lower cost of living to get petitions approved. In any case, the rule was struck down by a federal judge before it came into effect.

This past March, Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Dick Durbin (D-IL) introduced a bill intended to make the offshore outsourcing model less profitable, but it does so mainly via restrictions. For example, companies with more than 50 employees would be banned from hiring additional H-1B employees if more than half of their existing staff were foreign guest workers. This is intended to mostly affect offshore outsourcing firms, but according to some previous economic research, adding restrictions on guest visas often results in US-based companies outsourcing jobs rather than hiring more Americans, meaning it won’t have the effect the bill’s authors may have intended.

The EAGLE Act, which contains a similar clause restricting H-1B employees to no more than half of a firm’s workforce, would also remove the per-country cap on employment-based permanent residency applications, helping address the decades-long backlog for Indian foreign workers, and benefiting citizens of other countries such as China, where interest exceeds the annual cap. It may be a hopeful sign that the predecessor to this bill, the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act, was passed unanimously in the Senate in 2020.

Another bill, the STAPLE Act, which was proposed in 2017, would prioritize issuing work visas and permanent residency to foreign graduates of PhD programs at US universities. This is similar to programs in Canada and the UK that aim to attract international students to graduate programs, and then incentivize them to stay in the country permanently. Up to 100,000 international students per year who graduate from US colleges and universities would stay in the US if they could.

Ideas floated in the economics literature are varied, but often focus on making the annual cap more flexible and responsive to current economic conditions, perhaps by taking into account the labor market demand in specific occupations. But while a more rigorous evaluation of all petitions would help allocate slots to the most critical workers, the scale of such a program might be intractably costly. Other proposals involve auctioning visa slots to private-sector employers, or a points-based system similar to that used in Canada.

There’s certainly no shortage of solutions. The big challenge is the politics around the issue. There are data points that suggest a promising environment for reform: The foreign-born resident population in the US is at an all-time high, with around 1 million new green cards granted each year (most family-sponsored rather than employer-sponsored). According to Gallup poll data from 2021, the number of people in favor of increasing immigration has exceeded those who want to decrease it for the first time since Gallup began tracking attitudes toward immigration in the 1960s.

But there’s no denying that the current political environment around immigration is highly polarized in the wake of the Trump administration. Earlier efforts to pass comprehensive immigration reform have crashed on the shoals of political reality. If the US slips into an economic downturn, the politics of making it easier for foreign workers to come to the country will likely become even more challenging.

Can an incremental approach work? Neufeld believes that changes to the H-1B system will be more likely to pass in isolation. The Biden administration has already proposed a number of plans to reverse the changes made during the Trump administration to restrict immigration. But the harms of such policies on American workers — both real and perceived — mean that the politics of immigration will continue to be tricky.

In other words, the odds for reform remain slim, which poses a challenge for any efforts to turbocharge the US’s innovation agenda.