Nicolas Cage knows he’s a meme. He’s not happy about it. After making the mistake of googling himself a few years back, the charismatic actor discovered that his big on-screen performances had been translated into single-frame quips and supercuts, taken—like all memes, really—out of context, played for lolz, and in a manner that, frankly, makes Cage seem like a graduate from the Jim Carrey school of rubber-faced acting.

“Something like ‘Nick Cage loses his shit,’ where they cherry-pick meltdowns from different movies I’d made over the years,” he says. “I get that it’s all done for laughs, and in that context it is funny, but at the same time, there’s no regard to how the character got there. There’s no Act One, there’s no Act Two.”

This, Cage says, is not why he got into making movies. Back in the 1980s, when he was showing up in Fast Times at Ridgemont High and as the romantic lead in Valley Girl, there was no internet, no one turning him into a TikTok template. “So, as I’ve watched these memes grow exponentially and get turned into T-shirts and ‘You don’t say?’ and all that stuff,” Cage says, “I’ve just thought, ‘Wow, I don’t know how I should feel about this,’ because it’s made me kind of frustrated and confused.”

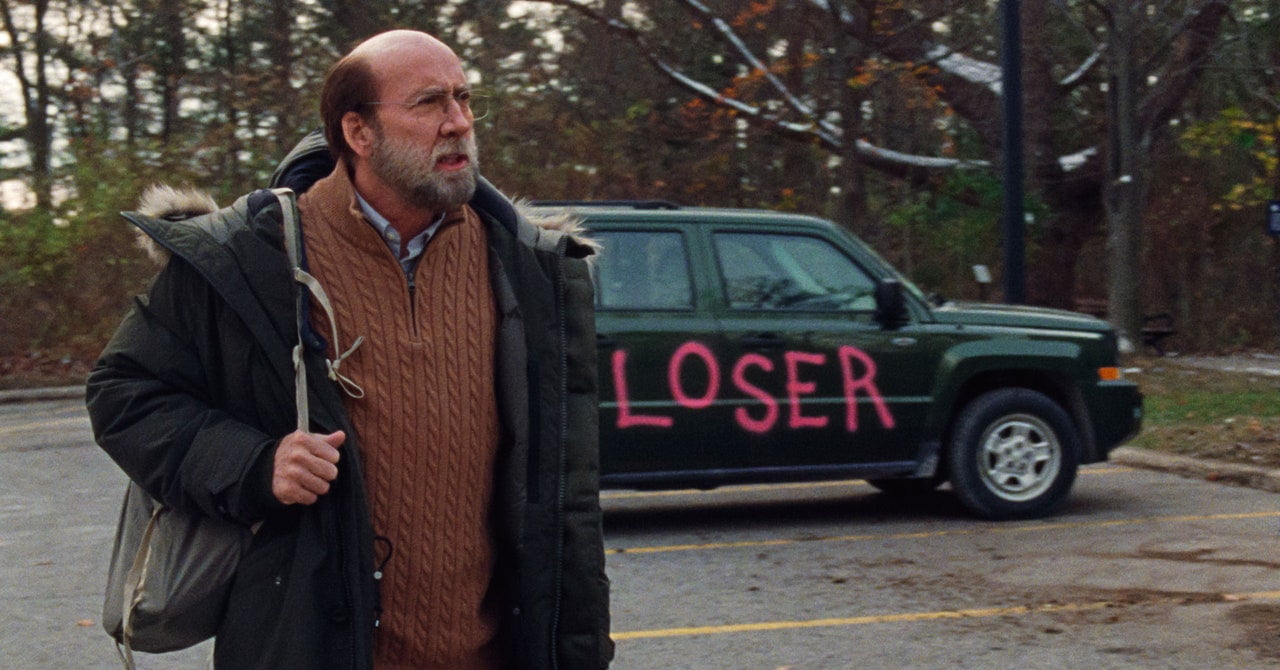

That’s part of the reason Cage signed on to do his latest movie, the A24 drama Dream Scenario, in which he plays Paul Matthews, a downtrodden university professor who suddenly starts to appear in the dreams of millions of people around the world. Directed by Sick of Myself’s Kristoffer Borgli, the film is a clever look at the trappings of instantaneous fame and at what it looks like when someone’s fame becomes bigger than they might be themselves—something Cage, who actually changed his name and leaned into a more bombastic persona early in his career, knows a little something about.

To mark Dream Scenario’s release, WIRED talked to Cage about where he’s at with his meme-ification these days, his dislike of social media, and why he’s going to make damn sure that no one can make an AI-generated Nick Cage after he shuffles off this mortal coil.

WIRED: Over the course of the movie, Paul struggles with who he thinks he is and who the world thinks he is, and how that’s constantly shifting around him. Is that something you’ve had to deal with over the course of your career in terms of “Nick Cage, Hollywood actor” versus “Nicolas Coppola, father and human being”?

Nicolas Cage: Very much so.

In an interview Kristoffer did with Variety, he brought up the word “egregore,” which is a word that not a lot of people know about.

I don’t. What is it?

It’s like a channel of consciousness or unconsciousness, where people start thinking about an entity, and they make it grow in a way where they’re all collectively thinking about the entity in a certain way. It can lead to things like myths or legends, but it can also lead to things that are painful and unattractive and unintentionally humorous. Anyway, I think his point was that my persona as Nick Cage has sort of outgrown the man that I am.

In what ways?

I say this without any kind of complaint, but I’ve had this kind of objective experience at times where it’s been like, “What is it that people really think about me?” You know, I live my life, and like anybody else I’ve made mistakes, but you do things or you do certain movies and that becomes your perception, where you’re the crazy guy. That’s not me at all. I live my life at home with my wife and my daughter, and I watch CNN, read a book, or watch a movie. But there’s another Nick Cage who’s this person that some people—not all people—want to want me to be, and he’s kind of a wild man.

Do you think that comes from the characters you choose, or is it something people have sort of projected onto you?

That is my fault, in a way, because I started out so young and I wanted to create a mythos or perception or persona and just get on the map by making a big noise, but it grew bigger than I had even anticipated.

In recent interviews, you’ve talked about your cameo appearance as Superman in The Flash, which you shot with one set of directions and intentions and which, though CGI, was turned into something else on-screen. You’ve also talked about the use of artificial intelligence in Hollywood, which you called “inhumane.” Where are you at now in terms of how your likeness can be used? Where do you draw the line in terms of, “OK, you can CGI me if we’ve made an agreement, but please don’t make a whole movie starring Nicolas Cage that I know nothing about,” or wherever you land?

You said it perfectly when you said, “We made an agreement.” That is the linchpin to it. There’s an agreement and a mutual understanding and a contract that you’ve gone into knowing both sides and knowing full well what we’re getting into.

I’m not saying they used AI on the Superman thing. Maybe they did. I don’t know. Maybe it was just CGI, but whatever it was, that’s not what I did on the set. As much as I love [director] Andy [Muschietti] and [sister and film producer] Barbara [Muschietti]—and I do think they’re great—it’s still not what I was told to do on set.

What about your performances in other films?

Let’s look at the end game: If I die and studios are taking [The Rock’s] Stanley Goodspeed or [Con Air’s] Cameron Poe or [Bringing Out The Dead’s] Frank Pierce or Peter Loew [of Vampire’s Kiss] or [Valley Girl’s] Randy or [Gone In 60 Seconds’] Memphis Raines and they’re just dumping it into a computer and the computer is going, “OK, let’s spit this script out, and let’s put that image here and have them do that …” First: I have no control over what they’re doing with my likeness. Second: Where’s the heart? I really believe that people are going to know that there’s no heartbeat in those eyes. There’s no heartbeat in that voice. There’s no heartbeat in that sound and movement. It’s not natural, it’s a robot, and I think that is very scary.

What about the times when agreements are made? Or are there any such agreements you would make?

Well, first of all, let me say that I don’t want anyone to do anything with my likeness when I’m gone. Whoever is in charge of my estate will make sure of that. But while I’m alive, if we have an agreement and you want to use [my image] as an art form and I can have some sort of collaboration with it, maybe there’s a conversation there to be had.

Sure. There is some version of AI performance that could be valuable. I just don’t know what that case is yet.

The most interesting use of AI that I ever read about—and I’m still not entirely sure how it works—but it’s to communicate with other species. They were talking about whales and how, if we can put the whale sounds in and correlate and correspond the whale sounds to their actions, that the artificial intelligence would be able to crack the code to their languages and that we could speak with them. That was interesting. But in terms of taking a work of art and appropriating it with a robot? Yeah, that’s not OK in my book.

You don’t want the voice of John Wayne to give you directions on Google Maps or something?

That’s a nightmare.

Does that relate in any way to why you’re not on social media? Like, does that kind of noise interfere with your relationship with the world?

The reason why I’m not on social media is very simple. I’m a romantic and I have great fondness for the Golden Age movie stars that I was inspired by. So I think that in some small way, I’m trying to keep with that aesthetic of the Golden Age movie star. Not too much access, maybe an occasional talk show or an interview like we’re doing, but don’t be tweeting every five seconds. To me, we’ve lost all mystery, and frankly I think it’s boring.

That’s a good point. We might not like Gene Kelly anymore if we knew his thoughts on every little thing.

You want to have something to dream about! You don’t want to know too much about the person you’re going to see in the movie.

What gets you going professionally right now?

What I want to do is to try to keep on this path of projects like Pig and Dream Scenario, where the scripts are starting to kick into high gear and the performances are switching to glide, because it’s more personal and it feels more truthful. I’m taking life experience and applying it to characters, and so I just want to try to stay on that path. I want the audience to feel that they’re in on a secret with me and that we have a private connection. I’ve never met you and you’ve never met me, but in that performance, you’re in on that secret.

You mentioned that you’re about to turn 60. Do you think about your legacy at all?

You know what? This was a good interview because you and I have been talking about a lot of things that are very real and on my mind. We’re talking about persona, we’re talking about the egregore that may have been built that is not necessarily me or who I was then but who I’m not now, and all of that is conversation about legacy.

So you have.

Ultimately, I think your legacy really is your children and whether you were the person you wanted to be. I just keep trying to get closer to that. I’m trying to spend more time with my family. I’m asking, “Am I reading enough books? Am I spending enough time with my kids?” All of that stuff is what the legacy is really about, and the rest of it—like Paul Matthews discovered—is pretty much out of my control. People are going to run with what they’re going to run with, and I don’t want to get too hung up on that.