Watertown, Massachusetts, has long been a popular place to live due to its proximity to Boston and its distinction as having a very large Target. Thanks to remote work, locals say the city is now becoming more attractive in its own right.

More people spending more of their time in Watertown has meant more urban amenities, like trendy stores, coffee shops, and even a potential food co-op, for the once sleepy suburban community.

Developers are buying up real estate in the hope that it will become a destination for the life science and innovation sectors. A once defunct mall is currently being converted into mixed-use space full of retail, residences, and restaurants that act more like a downtown than Watertown’s actual downtown. The Arsenal Yards project began before the start of the pandemic, but much of the leasing has happened after it. Already, 76 percent of its apartment space and 85 percent of its retail space have been leased. And its developers expect full occupancy next year.

Watertown is one of many American suburbs undergoing a similar transition as a consequence of the pandemic.

In the spring of 2020, many of the typical draws to cities — plays, nightclubs, restaurants — shut down. Space took on a premium, as small apartments close to others felt particularly claustrophobic. All of a sudden, a big home in the suburbs for the same monthly price as a tiny apartment in the city got a whole lot more attractive. The lifestyle also seemed safer, as you could travel in the isolation of your own vehicle and play in personal green spaces with less fear of infection. More companies than ever are allowing employees to work from home, and studies say that between 13 and 45 percent of the workforce is now remote some or all of the time.

As a result, a new rush to the suburbs is well underway. The number of net new households that moved to the suburbs grew 43 percent last year, according to data from the Wall Street Journal, compared to 2019. While that naturally slowed in the first half of 2021, urban areas are still losing people as they relocate to suburban and rural areas.

People who left their city apartments for houses in the suburbs aren’t just living in the suburbs, they’re working there now, too. In turn, the people and services these workers may have relied on in city centers are moving to the suburbs as well. All of this will affect which businesses thrive and what real estate develops in the suburbs. It could also change traffic patterns, exacerbate urban sprawl, and heighten inequality.

New suburban businesses and improved real estate trends could lead to revitalized communities, less travel, and better quality of living for some. But not everyone will benefit. Sprawl is bad for the environment and can make life worse for the poorest Americans.

The urbanization of the suburbs

People might be leaving behind the cities, but that doesn’t mean they want to forgo the city lifestyle. Even in the suburbs, people still want to be able to grab a quick coffee and a sandwich, and maybe a midday workout, and they don’t always want to do that at home. That demand has huge repercussions for commerce and construction. Research from Stanford’s Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom estimates that the largest cities have lost approximately 15 percent of their population and business to the suburbs.

Of course moving to the suburbs isn’t new: People young and old have long left the bustle and tight quarters of cities for the relative serenity and expanse of the suburbs. The postwar period created the suburbs as we know them, with many families accepting commutes in exchange for big houses outside urban hubs. In recent decades, that trend reversed. As newer generations glommed on to the entertainment, energy, and easy public transit of cities, population growth in many cities again outpaced suburbs beginning a decade ago.

But now suburbs are swelling again. Even before 2020, the suburbs had been urbanizing for years, as suburban dwellers sought the ease and efficiency of mixed-use areas that centered homes among commerce. But the increased prevalence of remote work has supercharged that progression by making it more viable.

This influx of people from cities to the suburbs will in some ways make the suburbs a lot more like the city, with more businesses located within walking distance of where people live. Achieving something that resembles urban density in the suburbs requires repurposing existing real estate to support a wider variety of businesses and functions, according to June Williamson, a professor of architecture and urban design at the City College of New York and co-author of Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia.

In the suburbs outside of Austin, Texas, another defunct shopping center, the Highland Mall, is being converted into a community college campus, office space, housing, and stores in addition to parks and trails. During the pandemic, Bell Works, a “destination for business and culture” that already had a location at the former Bell Labs headquarters in Holmdel, New Jersey, opened a second office, dining, and fitness space in another former AT&T campus in the Chicago suburbs. It bills itself as a “little metropolis in suburbia.”

Office real estate is also changing in the suburbs and mimicking the city coworking trend of the last decade. Prices for suburban office real estate haven’t declined nearly as much as downtowns, according to data from real estate firm CBRE. Working from the suburbs doesn’t necessarily mean working from home. For those whose homes aren’t suitable for work or who need space to meet or collaborate, or who just enjoy going into an office, a cottage industry of suburban office options is popping up.

“My competitor is right now your home and maybe Starbucks,” said Joel Steinhaus, a former executive at the coworking space pioneer WeWork and cofounder of Daybase, a coworking company that plans to open spaces in former suburban retail stores like Pier 1 Imports and Victoria’s Secret. WeWork and its model for flexible office space rose to prominence in the early 2010s, when city centers were thriving and companies were experimenting with new approaches to real estate. WeWork nearly went under just before the pandemic.

In some cases, suburban coworking may be more popular than in cities, according to new data from LiquidSpace, a marketplace for coworking space. Sacramento, a popular decampment for people moving from the high prices of the Bay Area, currently has more bookings on the site than San Francisco.

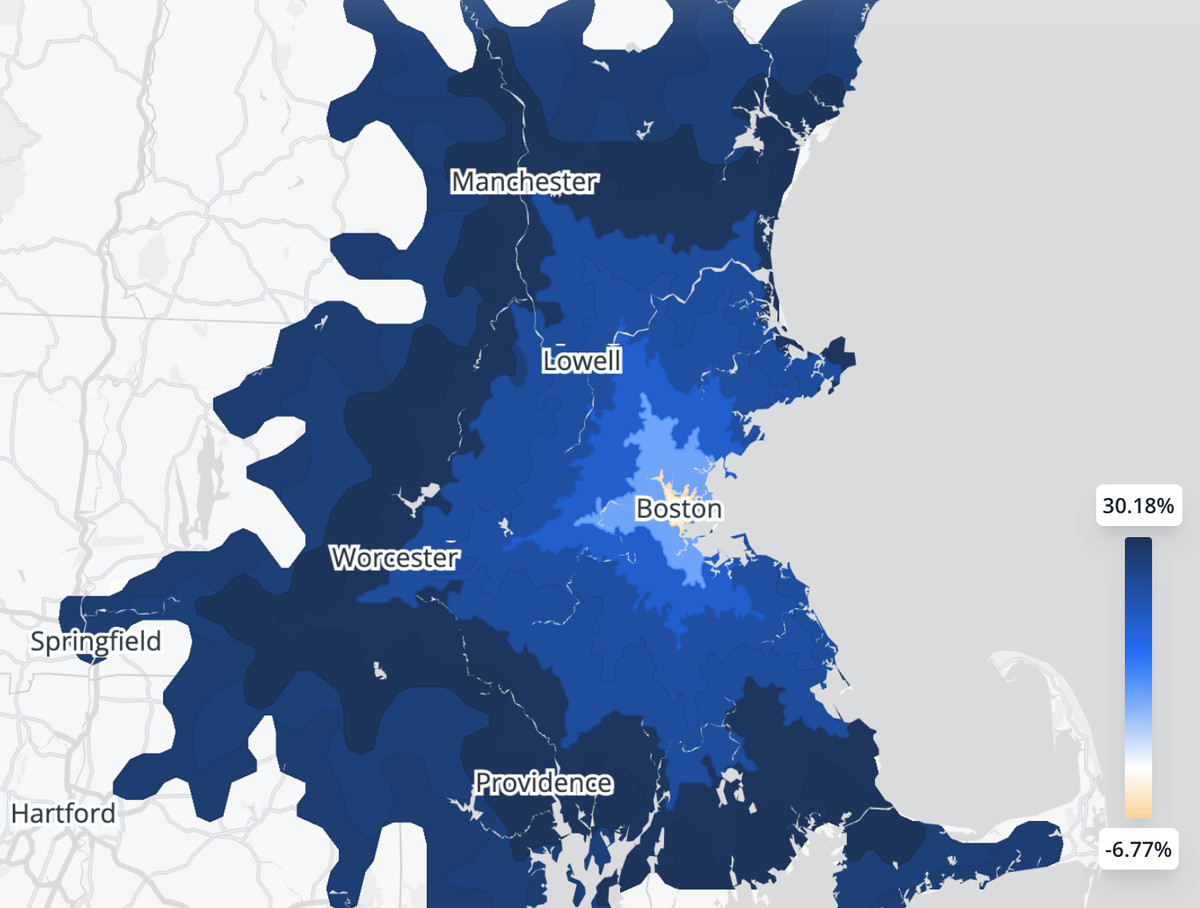

Housing in the suburbs is changing, too. It’s getting more expensive. Due to high demand and limited supply, housing prices in the suburbs and exurbs have skyrocketed, while prices in major city centers have stagnated. For example, central Boston saw its home value grow 9 percent in the last two years, while prices for places within commuting distance of the city like Worcester and Providence grew about 30 percent, according to data from Zillow and HERE Technologies.

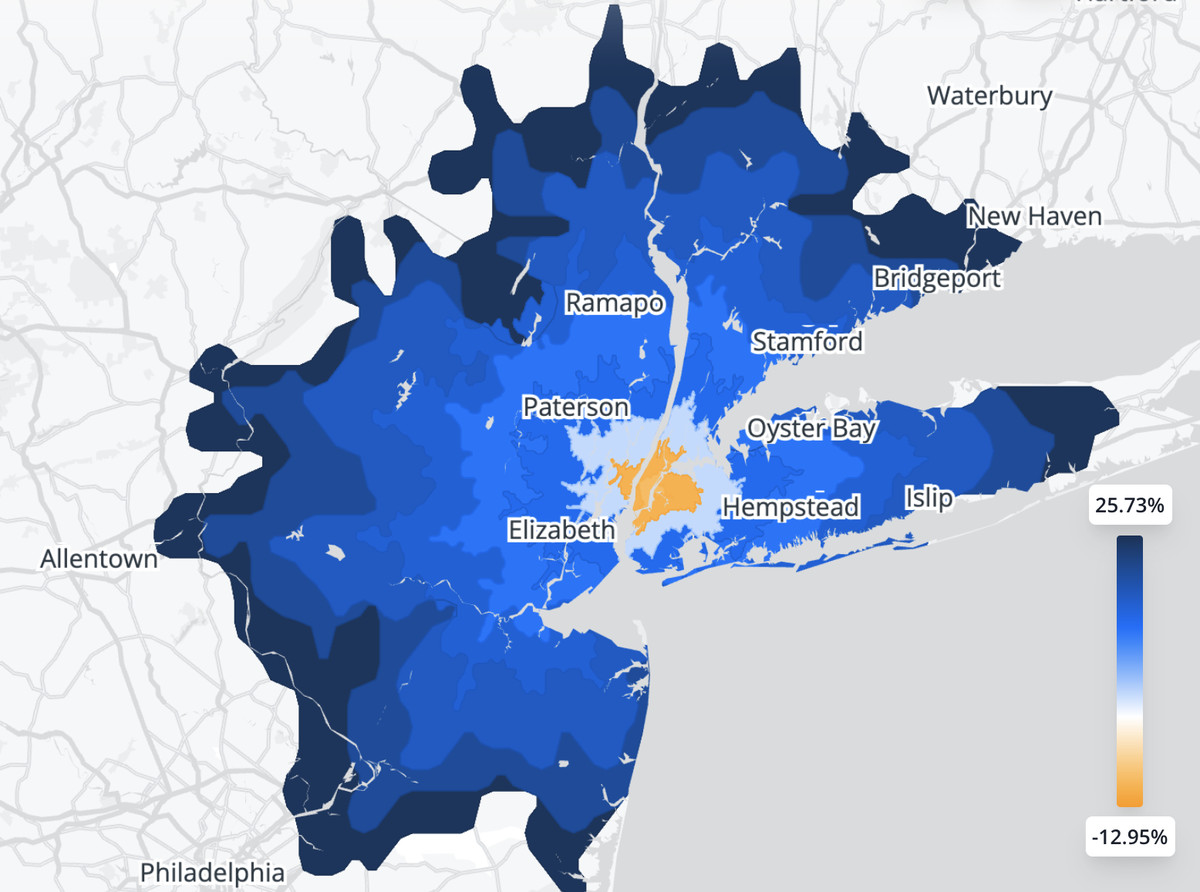

The difference is even more apparent in New York City — a city with a high concentration of remote workers — where the median home price in urban areas of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens actually declined while prices for homes 90 minutes away went up about 25 percent in the past two years.

“Small, expensive homes close to the office that previously benefited from a short commute as well as proximity to urban amenities — those homes saw a lot of their appeal decline,” Jeff Tucker, senior economist at Zillow, said. That’s because many of the city amenities were curtailed during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the home office became the new office.

“The relative value of space definitely went up,” he said.

While some question how long-lasting the move to the suburbs will be, the fact that people are buying so many homes makes it a difficult trend to unwind.

“I do not foresee a circumstance where a bunch of people who bought homes, even if they’re relatively further out, are going to just en masse turn around,” Zillow’s Tucker said. “The vast majority are going to build their lives out there.”

The rush to the suburbs will also affect what houses will look like. Instead of homogenous developments of large detached homes on half-acres of land, Tucker said, new construction includes more varied housing types to meet a broader range of consumer demand. That means construction of townhouses and apartment buildings in addition to the single-family homes of yore. Like the mixed-use retrofits mentioned earlier, these developments will be near or even include businesses within them.

Old problems showing up in familiar places

While the move to the suburbs will certainly benefit individuals, it threatens to exacerbate problems that have always plagued the suburbs — traffic, sprawl, inequality — unless we do something different this time.

When people talk about the benefits of remote work, skipping their commute — and its logistical and environmental challenges — is often the first thing they mention. However, the jury is out on whether remote work will actually lead to less driving.

Whether or not remote work leads to a net decrease in miles driven will depend on two main factors, according to Adie Tomer, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution: how many days a week people go into the office and how far from cities they move. We don’t really know the full extent of either yet. Most office companies have said they will operate under the so-called hybrid model, which means employees can split work between home and the office, but many haven’t hashed out the details yet or those details are still in flux. What we do know is that the majority of travel happens outside of commutes, and when people live in more suburban areas, their average trips to things like grocery stores or restaurants or day care are longer.

Another related issue to consider is how increased remote work could negatively affect mass transit. Fewer people taking mass transit into cities threatens the overall viability of those transit systems going forward. Many suburbs already lack good public transit, which makes it difficult for those with lower incomes — or without cars — to be able to get around, inhibiting their access to jobs and even basic necessities.

“Urban sprawl makes providing a robust public transit system very difficult,” Christina Stacy, a principal research associate at the Urban Institute, said.

Rising housing prices in the suburbs are making matters worse. New housing in the suburbs tends to happen at the outskirts, where land is available and less expensive, another factor that contributes to sprawl.

While some places like Minneapolis and, more recently, the state of California are embracing suburban densification by allowing more than one house to be built on a property, that’s by no means the norm and depends on the policies of a given municipality.

Residents in so-called “high-opportunity neighborhoods,” predominantly white areas with low poverty and unemployment as well as ample job opportunities, can be reluctant to embrace these changes.

“In a lot of high-opportunity neighborhoods, homeowners don’t want that increased density. They don’t want increased population. They worry about traffic and congestion and their house prices going down and schools being overcrowded,” Stacy said. That’s an impediment to changing zoning laws to allow more dense and mixed-use building.

If such changes don’t happen and prices continue to rise in the suburbs, poorer residents could get forced out of what’s becoming a more vibrant place to be.

“We need to be careful and make sure we’re preserving and developing affordable housing to allow households to remain in place,” Stacy said. “It’s important for the economy as a whole,” she said, noting that in order to have more amenities, you need people to staff those amenities as well. Mismatches between where lower-income people live and where jobs are located lead to higher unemployment rates and longer periods of joblessness. To combat these problems, suburbs will need better transit and more affordable housing near commerce centers.

While today’s suburbs are getting a facelift — younger people, more urban amenities, a more consistent revenue stream from remote workers — many of the problems that have plagued previous iterations of the suburbs persist. In many ways, the suburbs are more vibrant than ever. But to keep them that way, we need to avoid the pitfalls of the past.