Nick C., a 25-year-old food service worker who lives in western Iowa, remembers coming across TikTok influencer Connor DeWolfe’s videos about a year ago. They showed up on his For You feed, which is effectively TikTok’s homepage. Almost all of DeWolfe’s videos were about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD.

Nick recognized some of the symptoms described by DeWolfe as things he also struggled with.

“All of his content hit very close, and I binge-watched almost all of it,” Nick told Recode. “Then more ADHD content started appearing.”

He’d never been diagnosed with ADHD, but Nick was soon pretty sure he had it and that stimulants would help. He just needed a diagnosis and prescription. TikTok soon served up a way to get both: ads for a telehealth company called Done. Done said its providers could diagnose patients with ADHD and write prescriptions for “treatment” — typically stimulants — in a matter of days, at a time when in-person health was especially hard to find. Nick’s evaluation with one of Done’s nurse practitioners lasted about 15 minutes, he said. He walked out of his local pharmacy with a bottle of Adderall a few days later.

“Scary easy. Sketchy as hell. But it worked for me,” he said in a Reddit post at the time. “God bless TikTok for starting me on this journey.”

Nick is one of many people who have started the journey to an ADHD diagnosis on TikTok in recent years. Due to a combination of the pandemic and the rise of telehealth startups, it’s never been easier to come across social media content that will convince you that you might have ADHD, or services that will prescribe meds for it if they determine that you do.

But that content isn’t always coming from health care professionals. Much of the TikTok content can be considered inaccurate or misleading. Meanwhile, it’s especially important that ADHD assessments are careful and thorough so that health care professionals can rule out other conditions with the same or similar symptoms as ADHD, look for coexisting conditions, and screen for people who are seeking ADHD meds like Adderall to abuse. Diagnosing someone with a condition they don’t have — and prescribing meds to treat it — means they aren’t getting diagnosed and treated for whatever condition or conditions they do have. And ADHD meds aren’t effective when taken by people who don’t have ADHD, but they can be addictive and abused.

These new kinds of services wouldn’t have been possible just a few years ago. During the pandemic, the government waived a rule requiring that patients see an in-person provider before a controlled substance can be prescribed. This allowed totally remote telehealth or virtual care apps, which Silicon Valley has thrown money at over the last few years, to prescribe controlled substances, all through their mobile app. Some of those startups saw an opportunity here: Cerebral, for example, added ADHD treatment to its offerings in early 2021 and reportedly increased its sales tenfold, signed up tens of thousands of new patients, got hundreds of millions of dollars in funding, spent big on social media advertising, and reached a valuation of $4.8 billion.

Between the beginning of 2020 and the end of 2021, prescriptions for Adderall and its generic equivalents increased by nearly 25 percent during the pandemic for the 22-44 age group, a trend that health care analytics firm Trilliant Health attributed to “the emergence of digital mental health platforms.” At the same time, those medications have experienced shortages.

Some of those digital health platforms are having trouble now. Investigations by Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal earlier this year have alleged that certain telehealth companies are too quick to diagnose paying patients with ADHD, after boasting of easy access to medication in TikTok ads. Major pharmacy chains have even stopped filling prescriptions from some of the most prominent ADHD telehealth services. Cerebral, once one of the space’s biggest providers, has stopped prescribing those meds to new patients amid multiple reported federal probes into its practices, and will stop prescribing them altogether in October.

But Done doesn’t appear to be going anywhere — and its direct spending on TikTok ads more than doubled between May and July, Pathmatics, a digital marketing analytics company, told Recode.

#ADHDTikTok can be a helpful community and a great marketing opportunity

TikTok boomed during the pandemic, growing from 583 million monthly active users in the first quarter of 2020 to 1.47 billion of them by July 2022, according to Business of Apps. That user base skews younger and spends more time on the platform, on average, than its competitors. It’s known for memes and dance videos, but it’s also popular for its many communities, some of which are dedicated to neurodiverse people and mental health conditions. TikTok videos using the #ADHD tag have over 14 billion views, and those tagged with #ADHDTikTok have over 4 billion. There are also plenty of ADHD influencers with thousands, even millions, of followers. They typically post about what it’s like to live with the condition, share productivity tips, and list off myriad symptoms.

“I do think social media has been very helpful and a positive influence for people who are neurodiverse,” said George Sachs, a psychologist who specializes in diagnosing and treating ADHD. “The knowledge and the education you can get, and the sense of community and acceptance, is really important.”

Sachs says he often recommends that newly diagnosed patients go to TikTok, where they’re likely to find support and encouragement from people who have the same conditions they do.

Ari Tuckman, a psychologist who specializes in ADHD, said. ”Most of the people who are doing it are not clinicians. They might be speaking about their experience, but that doesn’t make it relevant, necessarily, to everybody else’s experience. ADHD doesn’t look the same for every person who has it.”

A recent study in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry analyzed 100 TikTok videos about ADHD and found that more than half of them were misleading, and only a fifth were considered “useful.” One of the study’s authors, Dr. Anthony Yeung, told Recode that he did the study because he and other clinicians were seeing an increase of people who thought they had ADHD, and a “considerable portion of them” often based that self-diagnosis on information they saw on TikTok.

“If one out of every two videos is misleading — and you’re using the app for an hour a day, and you’re just consuming that information — then pretty quickly you develop either a distorted view or a very different perspective,” Yeung said.

That means TikTok’s notoriously powerful algorithm may feed people a steady stream of inaccurate or incomplete information about ADHD as well as ads promoting services that offer the possibility of getting an ADHD diagnosis and prescription in just a few days.

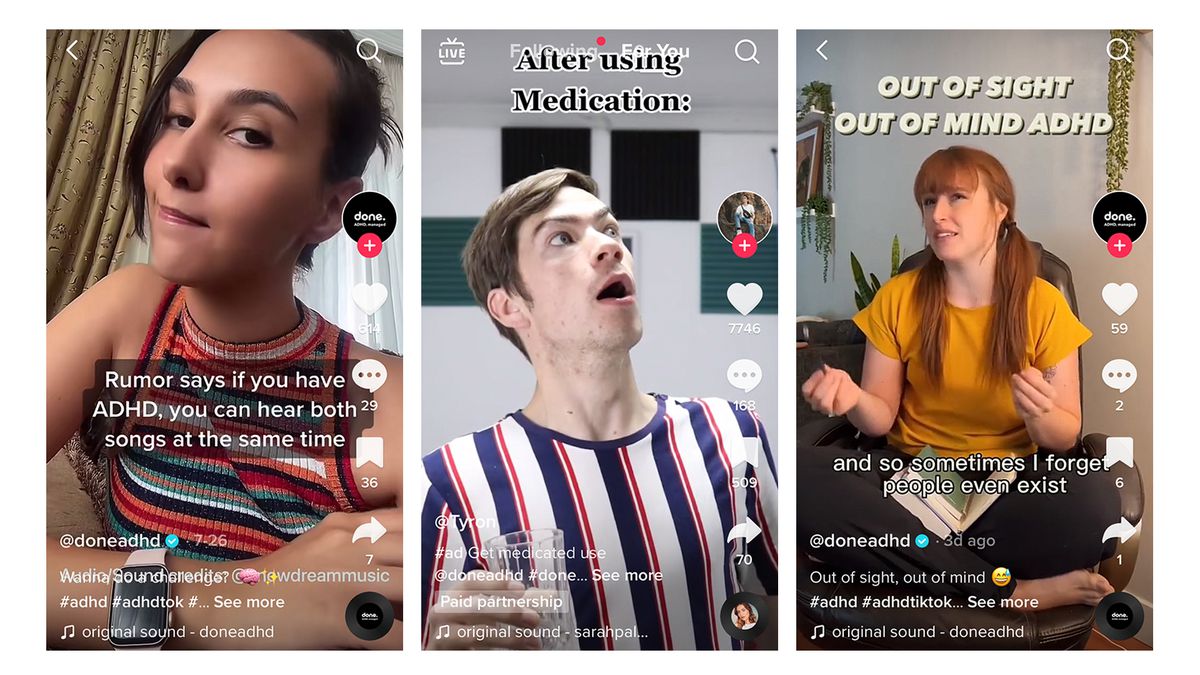

Some of these companies are well aware of the value in advertising to this community. Cerebral, which treats multiple conditions including ADHD, spent $13 million on TikTok ads between January and May of 2022, according to Pathmatics, making it the platform’s third-biggest ad buyer overall during that time. Done, which only treats ADHD, spent $3.4 million on TikTok ads between January 2022 and the end of July. Done also places ads on Snapchat and Instagram, but spent about half of its budget on TikTok during that period, Pathmatics told Recode. And that doesn’t even count the money Done spends on ads through TikTok influencers.

Done also promotes from its own account information that could be considered misleading. One video implies that people with ADHD can hear two songs at the same time — something that plenty of people who don’t have ADHD can also do. (Done said that the ad says the ability to hear two songs is a “rumor” and not meant to be or described as professional advice.) Another depicts the traditional ADHD assessment process as consisting of a dismissive and uncaring doctor who makes their patient wait a year for an appointment that costs “at least” $1,000. (Done claims it does not discourage people from using traditional providers.)

“The Done marketing team operates through a rigid and thorough protocol to develop relevant and accurate marketing collateral committed to educating and informing Done’s patients and audiences,” Done said.

Unlike prescription drug companies, which are allowed to advertise on social media platforms but have many restrictions about what they can say, a service that merely provides access to those drugs has far fewer rules to follow. And TikTok is under no legal obligation to ensure that what its users post is accurate, though the company says it “cares deeply about the well-being of our community,” noting that it invests in digital literacy education to help users understand when the content they’re seeing is an accurate fact and when it’s just an opinion.

“We strongly encourage individuals to seek professional medical advice if they are in need of support,” the company added.

The problems and potential of ADHD telehealth

Most of the telehealth services offering ADHD diagnoses work by charging a patient for an initial consultation and assessment, which most companies offer within a few days of signing up, if not the same day. That consultation may be quite brief. If the patient is diagnosed with ADHD in that assessment, they might get a prescription for meds. They then have to pay fees to see their providers for refills. Some services, like Done, make patients pay monthly subscription fees (Done is currently $79). Other platforms, like Klarity, charge per appointment.

Done says it “does not manage how quickly a provider diagnoses and what treatments a provider uses.” But the company’s social media profiles also prominently feature pill emojis, and its website boasts of 30-minute appointments, saying “it’s as easy as this.” Done says its providers are able to evaluate patients that quickly by getting some information from patients ahead of time, including questionnaires that screen for ADHD and other conditions and providing their medical history.

“While we would love to spend as much time as possible with our patients, we are also committed to helping as many patients as possible,” Done said.

For people who have ADHD, that ease might mean access to care they need but otherwise can’t get. In-person care might be too far away or too costly, and it might take months just to get an assessment.

Despite these hiccups, some experts are optimistic about the future of telehealth and the potential of companies like these — as long as they make patient care rather than profit their focus.

“Like all new ideas, sometimes they have to fail so you can see what variables need to have better control. I think that with all of these companies, if they did have tighter control over some of these factors, it would align better with what their mission is,” Arroyo said.

“This is just the beginning stages. There were some missteps there, I think, in cutting corners,” Sachs said. “But I think the trend is good if there are safeguards in place, and if there’s training.”

Done acknowledged some of the criticism that’s been thrown its way, but said it believes the services and access it offers its patients are a net positive.

“As we grow, we run the risk of being criticized for treating individuals who may not have been treated before. Any medical organization that treats a large volume of patients may make errors of ‘overdiagnosing’ and/or ‘overtreating’ — but we believe that helping individuals outweighs this potential cost,” the company said in an email.

Nick is now six months into his ADHD treatment, and he has no regrets. He says he’s seen “significant improvements” in his symptoms, and his Done provider is “very responsive and on top of things.” He has no plans to switch to a traditional provider unless the Drug Enforcement Administration shuts Done down — which he suspects will happen sometime soon.

“There is zero reason any of these services should still exist,” he said.