The biggest fight of the generative AI revolution is headed to the courtroom—and no, it’s not about the latest boardroom drama at OpenAI. Book authors, artists, and coders are challenging the practice of teaching AI models to replicate their skills using their own work as a training manual.

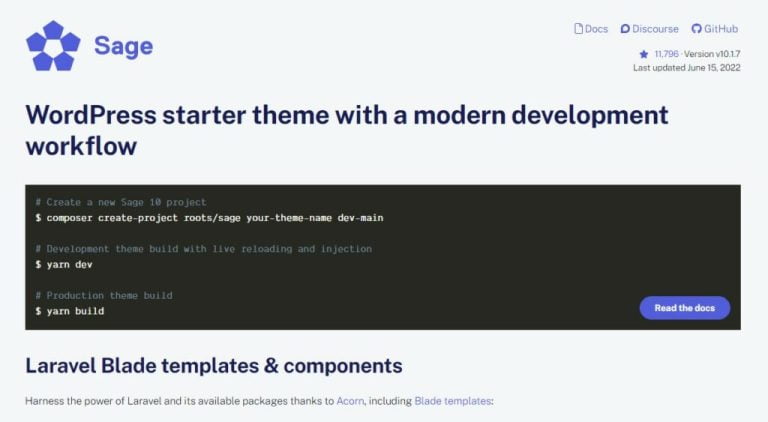

The debate centers on the billions of works underpinning the impressive wordsmithery of tools like ChatGPT, the coding prowess of Github’s Copilot, and artistic flair of image generators like that of startup Midjourney. Most of the works used to train the underlying algorithms were created by people, and many of them are protected by copyright.

AI builders have largely assumed that using copyrighted material as training data is perfectly legal under the umbrella of “fair use”—after all, they’re only borrowing the work to extract statistical signals from it, not trying to pass it off as their own. But as image generators and other tools have proven able to impressively mimic works in their training data, and the scale and value of training data has become clear, creators are increasingly crying foul.

At LiveWIRED in San Francisco, the 30th anniversary event for WIRED magazine, two leaders of that nascent resistance sparred with a defender of the rights of AI companies to develop the technology unencumbered. Did they believe AI training is fair use? “The answer is no, I do not,” said Mary Rasenberger, CEO of the Authors Guild, which represents book authors and is suing both OpenAI and its primary backer, Microsoft, for violating the copyright of its members.

At the core of the Authors Guild’s complaint is that OpenAI and others’ use of their material ultimately produces competing work when users ask a chatbot to spit out a poem or image. “This is a highly commercial use, and the harm is very clear,” Rasenberger said. “It could really destroy the profession of writing. That’s why we’re in this case.” The Authors Guild, which is building a tool that will help generative AI companies pay to license its members’ works, believes there can be perfectly ethical ways to train AI. “It’s very simple: get permission,” she said. In most cases, permission will come for a fee.

Mike Masnick, CEO of the Techdirt blog and also the Copia Institute, a tech policy think tank, has a different view. “I’m going to say the opposite of everything Mary just said,” he said. Generative AI is fair use, he argued, noting the similarities of the recent legal disputes with past lawsuits, some involving the Author’s Guild, in which indexing creative works so that search engines could efficiently find them survived challenges.

A win for artist groups would not necessarily be of much help to individual writers, Masnick added, calling the very concept of copyright a scheme that was intended to enrich publishers, rather than protect artists. He referenced what he called a “corrupt” system of music licensing that sends little value to its creators.

While any future courtroom verdicts will likely depend on legal arguments over fair use, Matthew Butterick, a lawyer who has filed a number of lawsuits against generative AI companies, says the debate is really about tech companies that are trying to accrue more power—and hold onto it. “They’re not competing to see who can be the richest anymore; they’re competing to be the most powerful,” he said. “What they don’t want is for people with copyrights to have a veto over what they want to do.”

Masnick responded that he was also concerned about who gains power from AI, arguing that requiring tech companies to pay artists would further entrench the largest AI players by making it too expensive for insurgents to train their systems.

Rasenberger scoffed at the suggestion of a balance of power between tech players and the authors she represents, comparing the $20,000 per year average earnings for full-time authors to the recent $90 billion valuation of OpenAI. “They’ve got the money. The artist community does not,” she said.