If you could choose to be alive at any point in human history, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better moment than right now. We’re living longer, richer lives with better access to clean water, education, electricity, and basic human rights than ever before.

We can celebrate human progress without becoming complacent — after all, there’s never any shortage of bad news to report, and gaping disparities between rich and poor countries will remain far into the future. But McCartney and Lennon were onto something when they sang about things getting better all the time, even if they were talking about love, not life expectancy.

But for just about every animal species besides Homo sapiens, today is probably the worst period in time to be alive — especially for the species we’ve domesticated for food: chickens, pigs, cows, and increasingly, fish.

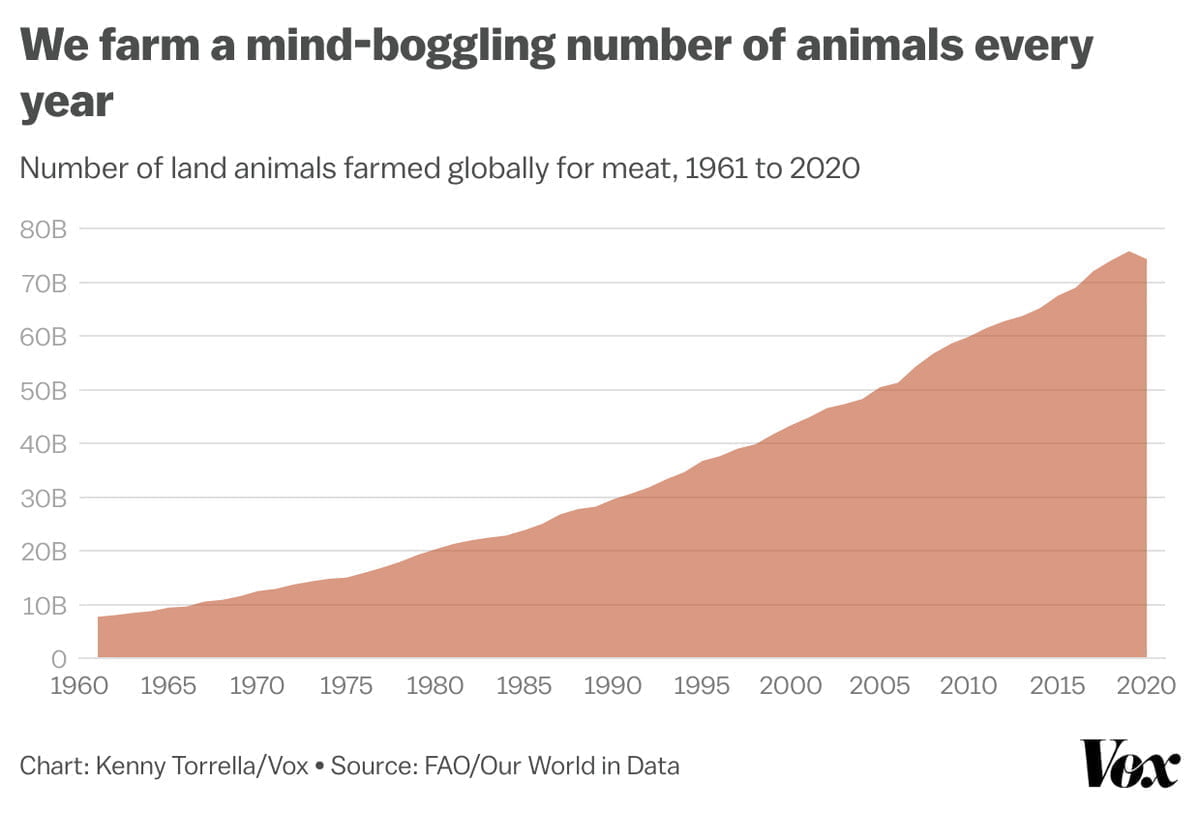

That’s because a not-insignificant amount of human improvement has come at the direct expense of these animals, with rapid human population growth — and all those people leading longer, richer lives — creating a surge in demand for cheap meat over the last 60 years.

Human prosperity and animal suffering exist in a kind of twisted symbiosis: Economic growth leads to more food production and consumption, which in turn results in faster population growth and longer life expectancy, which then requires more intensive, factory-farmed meat to satiate growing populations.

The cycle has been miraculous for humans. For all the problems of our global food system — including a recent rise in world hunger due to the Covid-19 pandemic and price hikes for grain caused by the war in Ukraine — far fewer people are undernourished today than they were in the 1970s, and the specter of famine has largely diminished. But the cycle has been disastrous for the environment and animals, as hundreds of billions of them are now raised on factory farms each year, accounting for about 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Growing prosperity and human population have also meant that more and more animals are being used in testing for drug development and consumer products, and that deforestation of massive areas of wildlife habitat is increasing — primarily for beef and livestock feed.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. An exception to this rule — that some of human flourishing has come at the cost of animal welfare — is pets; US euthanasia rates at pet shelters have plummeted since the 1970s. And perhaps more consequentially, we’re at the start of what might be a moral revolution in our relationship to other animals. Countries are passing laws to ban the worst factory farming practices; leading philosophers are calling for an expansion of who we include in our moral circle; and scientists are building technologies that could one day eliminate the use of animals for food, medical research, and textiles.

Though currently low levels of meat consumption across Asia, Africa, and Latin America are projected to skyrocket in the coming decades, they’ll likely still be much lower than consumption in the West. But meat eating seems to have more or less peaked, or will at least grow very slowly, in richer parts of the world like the US and Europe.

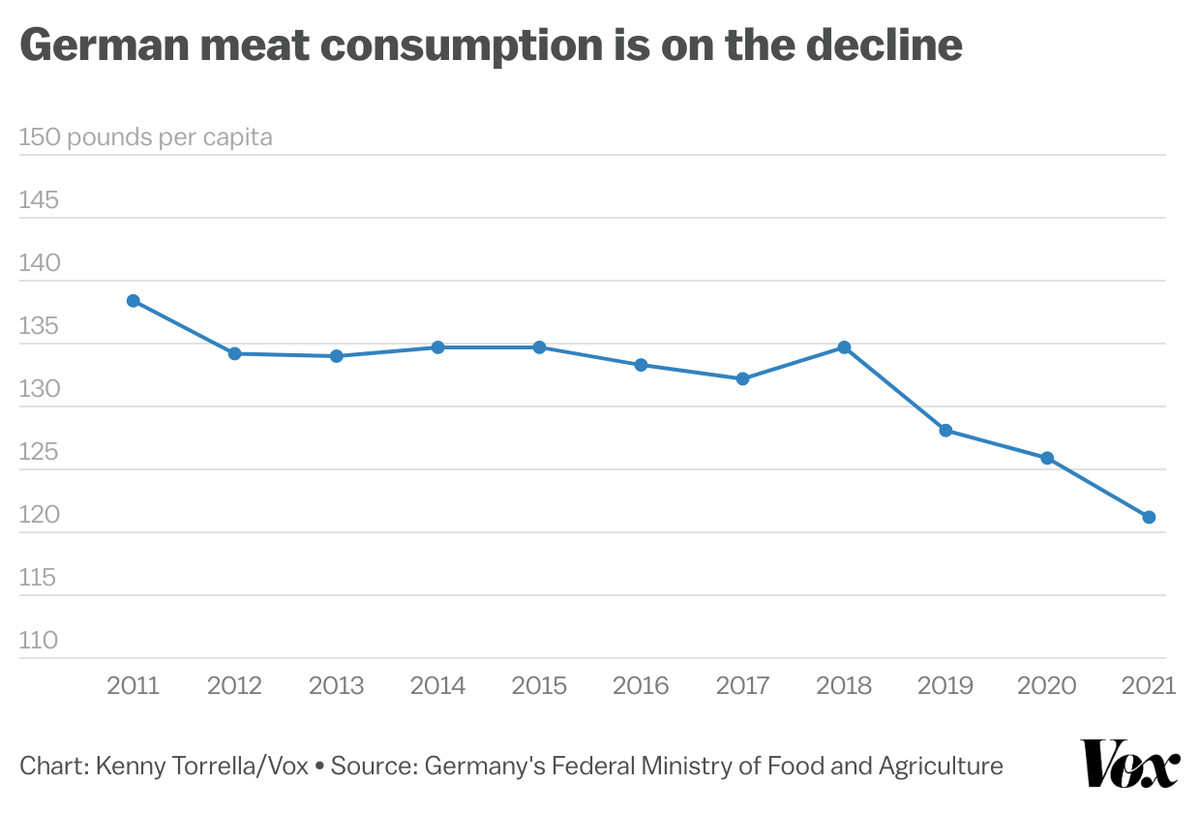

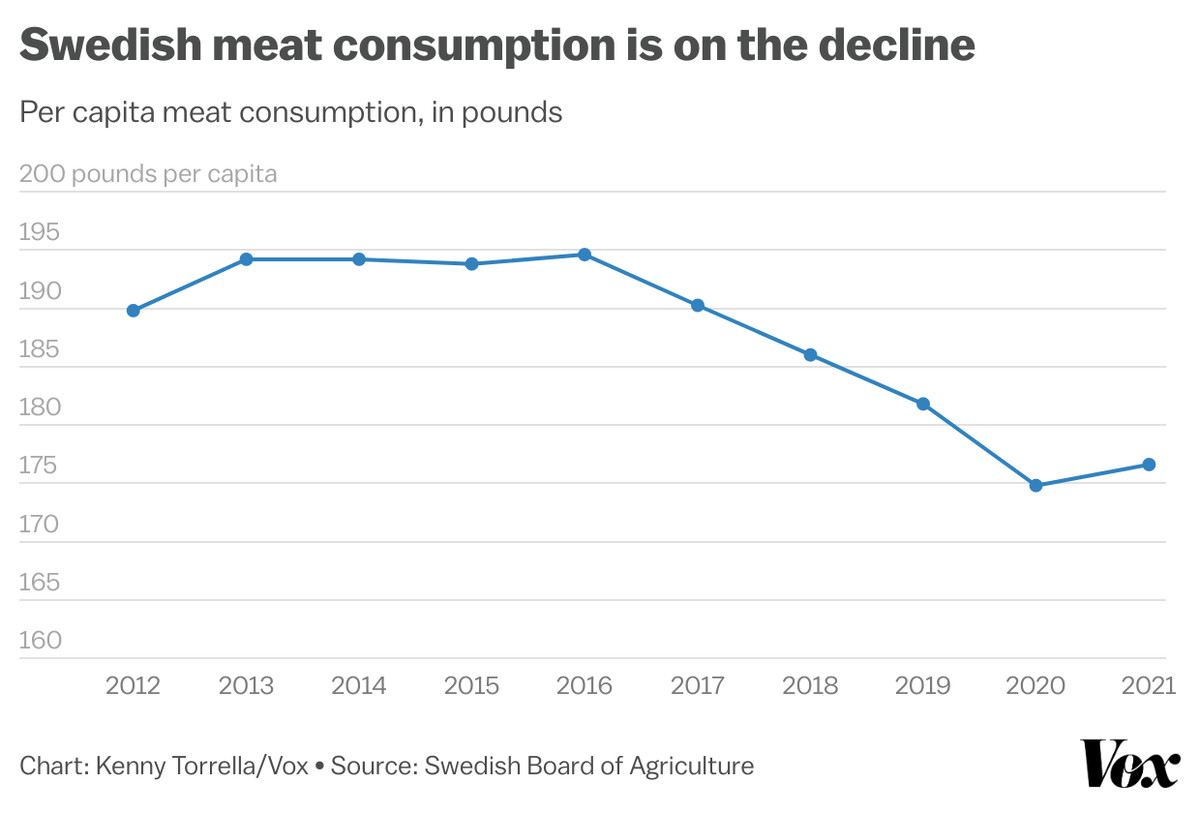

Some countries, like Germany and Sweden, are actually starting to eat less of it overall, thanks in part to heightened campaigning over the environmental toll of meat production. The European Commission projects a 4 percent decline in per capita meat consumption within the bloc by 2031.

However, declining consumption is relative. Recent figures show Sweden’s per capita meat consumption is almost five times that of Pakistan’s, while the average German eats about as much meat in a month as the average Nigerian does in a year.

But just as some countries have figured out how to decouple greenhouse gas emissions from economic growth — improving quality of life while lowering the national carbon footprint — someday we might do the same for animal welfare.

We’ve made 11 charts that lay out the grim case for how human progress has too often come at the expense of animal welfare, while indicating some hope for a future where both humans and domesticated animals can flourish together.

In 1961, there were 2.5 land animals farmed for each human; in 2020 there were 9.5, a 280 percent jump. There’s now 74 billion of them churning through our farms and food systems each year.

But meat from all those animals is not consumed equally around the world: The average American consumes around 273 pounds of meat per year while the average Ethiopian purchases just 12 pounds.

It’s not just sheer numbers, however. As demand for meat has risen, conditions for animals have worsened. To raise those tens of billions of chickens, pigs, and cows, farmers and meat companies have prized efficiency over animal welfare and environmental conservation. The resulting factory farming model, first built in the United States and Europe in the post-World War II era, has since spread across the globe.

By one estimate, almost three-quarters of farmed land animals in the world are reared in factory farms, in which they’re crammed tightly into industrial warehouses and given little to no fresh air, sunlight, or access to the outdoors. And nearly all of the land animals raised for food are chickens — around 95 percent of them.

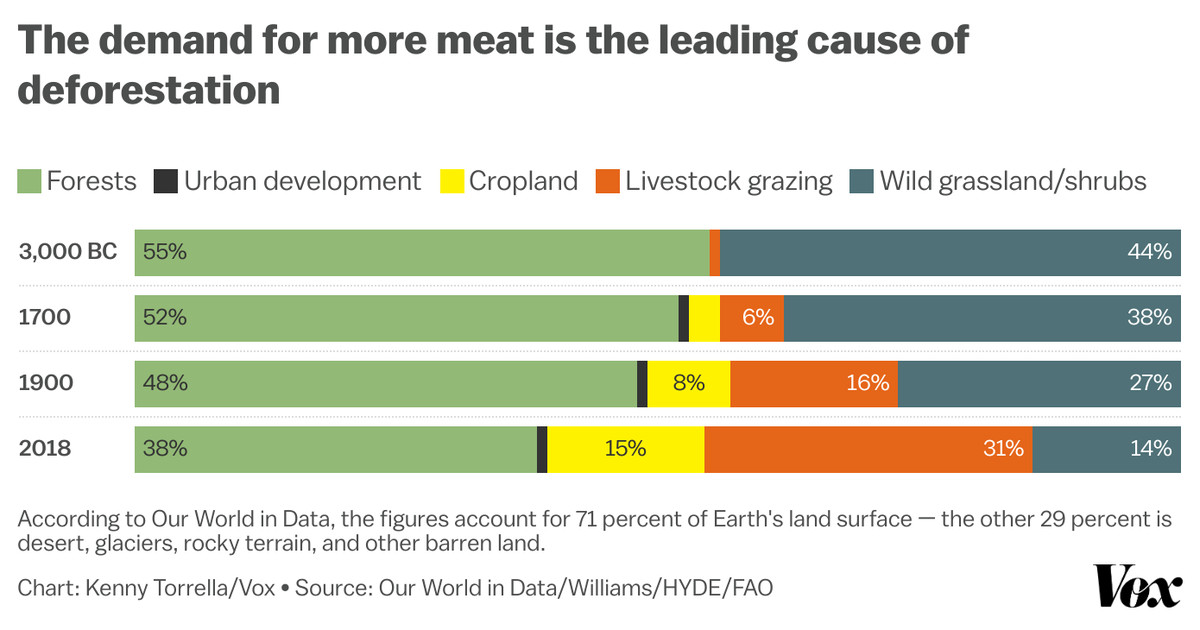

The rising demand for meat, especially beef, doesn’t just mean more animals suffering on farms. It has also destroyed wildlife habitats in the Amazon rainforest and elsewhere in the tropics.

Agriculture — clearing trees for farmland — is the overwhelming cause of deforestation. In 1700, just 9 percent of the world’s forests and wild grasslands had been cleared for agriculture. Today, it’s 46 percent, primarily for livestock grazing, growing crops like soy to feed pigs and chickens, or for the production of palm and other oils.

Meat production doubly affects climate change, too. Not only do the animals we farm emit greenhouse gases, all that related deforestation releases carbon stored in trees, contributing to climate change and accounting for up to 10 percent of human-induced carbon dioxide emissions.

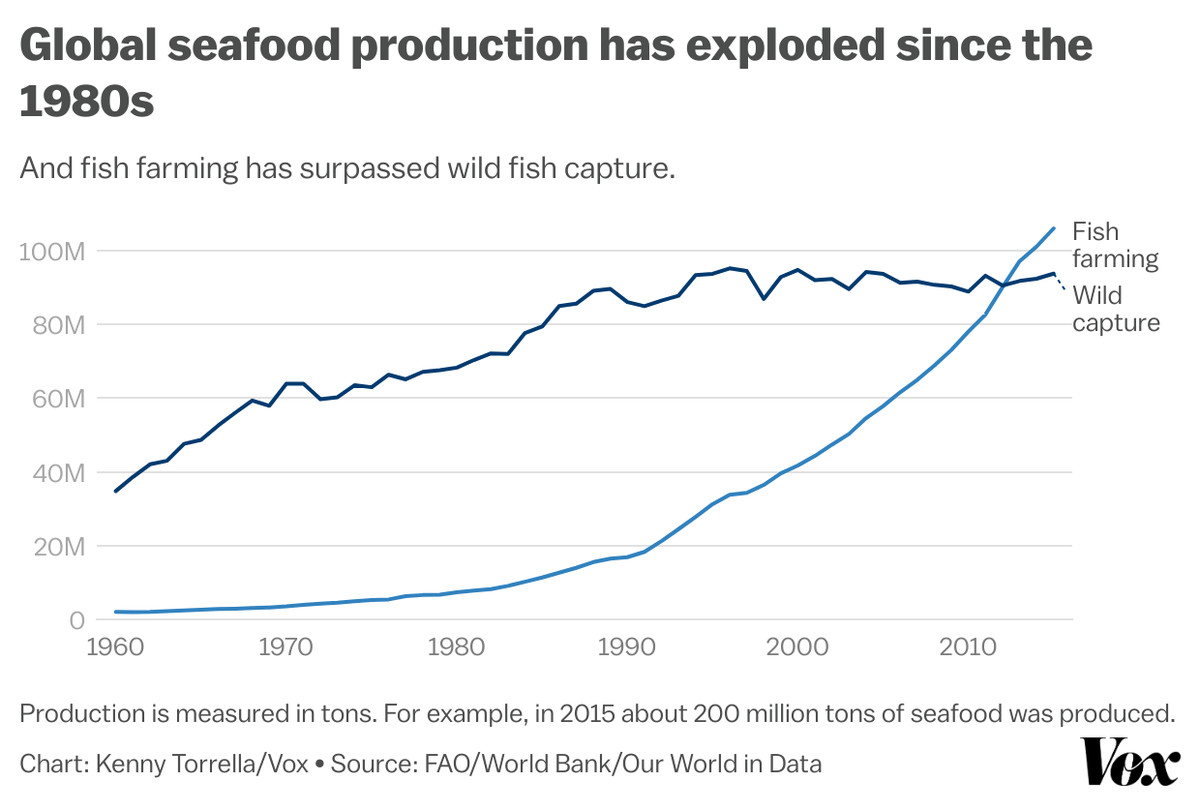

The world produces around 200 million tons of seafood each year, but we don’t know how many animals that represents, as fish are measured by weight, not individual animals. But one group — appropriately called Fish Count — estimates that anywhere between 1 trillion to 3 trillion fish and crustaceans, like shrimp and crabs, are eaten each year (though this figure excludes wild-caught crustaceans, which the group hasn’t yet calculated).

The farming of land animals is a mere rounding error when compared to seafood production.

To put that into perspective, there are far more fish and crustaceans raised and caught for food each year — 1 trillion on the lower end — than there are humans who’ve ever existed, which is estimated at 117 billion people.

Seafood production is unusual in that it relies on both catching fish in the wild, and farming them on land or in offshore pens. For most of human history, wild-catch was the dominant method. The fish we caught lived normal fish lives and only experienced pain for the minutes or hours it took to catch and slaughter them. Then, in the 1980s, fish farming took off over fears of declining wild fish populations.

Now, more than half of the fish we eat comes from fish farms. They are essentially underwater factory farms, repeating many of the same problems found in farms on land: overcrowding, disease, and injuries.

Just as agriculture has transformed natural landscapes through deforestation, commercial fishing and fish farming have transformed oceans through pollution and overcatching. Discarded fishing gear accounts for around 10 percent of plastic found in the ocean, offshore fish farms pollute oceans, and the fishing industry is a leading threat to coral reefs, according to the US National Ocean Service.

If the demand for meat and seafood keeps rising, the toll on both the environment and animal welfare will be immeasurable. But there’s some early evidence that at least some countries may have hit their peak of meat consumption.

Over the last decade, Germany’s per-capita meat consumption fell 12.3 percent. Experts attribute much of the change to the country’s environmentalists, especially the younger set, who’ve raised a big stink about meat’s contribution to climate change. Other factors may have contributed to the drop too, such as increased awareness of animal cruelty and labor issues in the meat industry.

Germany isn’t alone — Sweden’s meat consumption has been on the decline since 2016.

Sweden’s per-capita meat consumption fell 9.2 percent from 2016 to 2021 (with a slight uptick from 2020 to 2021).

Anna Harenius of Djurens Rätt, a Swedish animal protection group, told me environmental awareness also played a role in the country’s shift to plant-based eating (after all, Sweden is home to perhaps the most notable vegan environmentalist, Greta Thunberg).

Harenius also says Swedes are unusually fond of boycotts. They even boycotted the company that put Sweden on the plant-based map, Oatly, for taking investment from Blackstone, a private equity firm that’s linked to deforestation in the Amazon rainforest and whose CEO has been a donor and adviser to Donald Trump.

The two countries demonstrate that change is possible even without forceful government policy, which goes against the idea, often floated among some environmentalists, that individual choices don’t matter all that much. Germans and Swedes just kept hearing the arguments for reducing meat consumption and seemed to take it to heart. (There’s no doubt that in order to move the needle on meat and dairy production’s environmental impact, governments will need to take stronger action at some point, as they have on energy production and transportation.)

Humanity has become accustomed to eating a lot of meat, and cheap meat at that. Campaigns to persuade people to eat less of it might work in some countries, but for most consumers, rich or poor, it’s a hard sell. Enter alternative protein products that aim to provide the taste and nutrition of meat and dairy without killing animals.

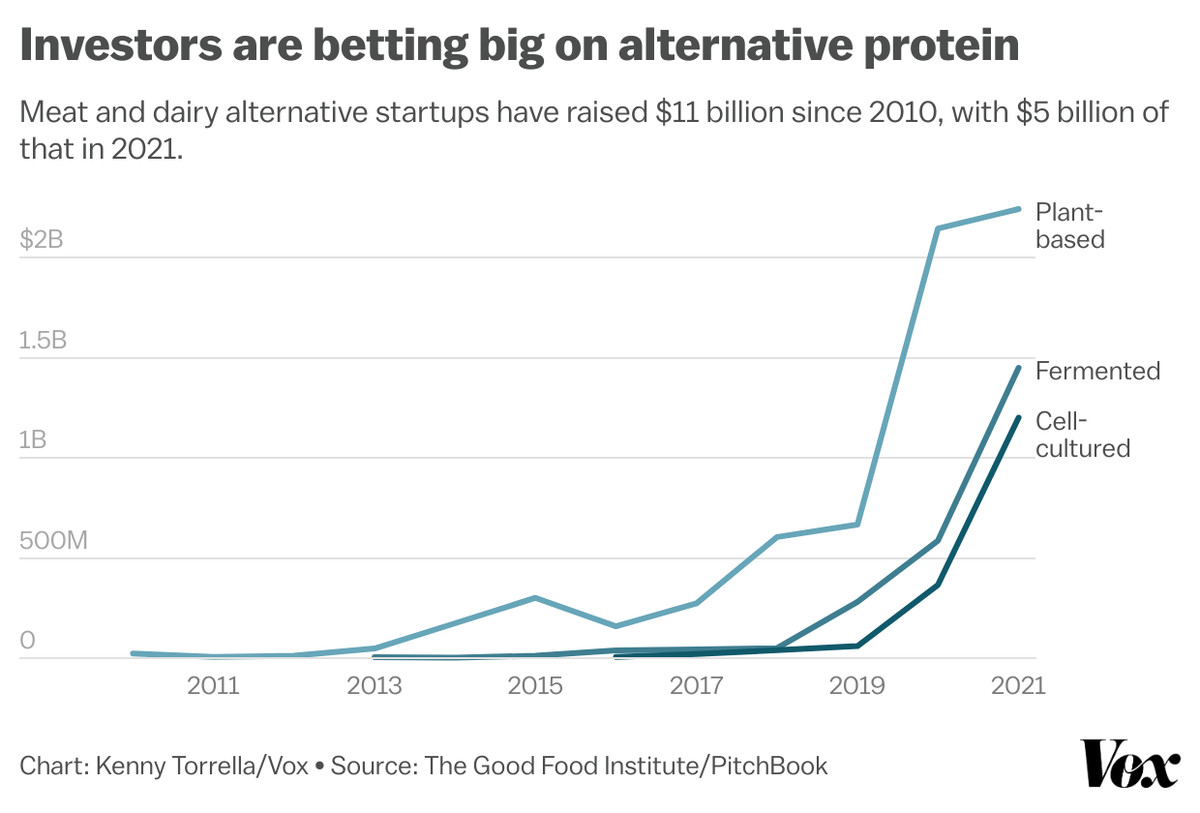

Alternatives to animal meat have been around for centuries, but only in recent years have they become more like meat than plants. Now, investors — and a growing ecosystem of scientists and advocates — are eager to make them taste much better and come down in cost.

Until 2016, a few companies dominated the plant-based meat market. Then, burgers from Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods changed the game. Suddenly, consumer interest in plant-based meat spiked, and investors followed. In 2013, meat and dairy alternative startups received just $23 million in funding. In 2021, it was $5 billion.

Much of that went to plant-based startups, but companies that are racing to commercialize cell-cultured or “cultivated” meat — meat grown from animal cells — have gotten in on the frenzy. So have companies using different methods of fermentation.

Some governments, including the US, are funding alternative protein research, while others are even investing in plant protein companies. But it’s going to take awhile to see if all that investment pays off and actually changes how we eat; plant-based meat is still estimated to comprise less than 1 percent of total meat produced in the US.

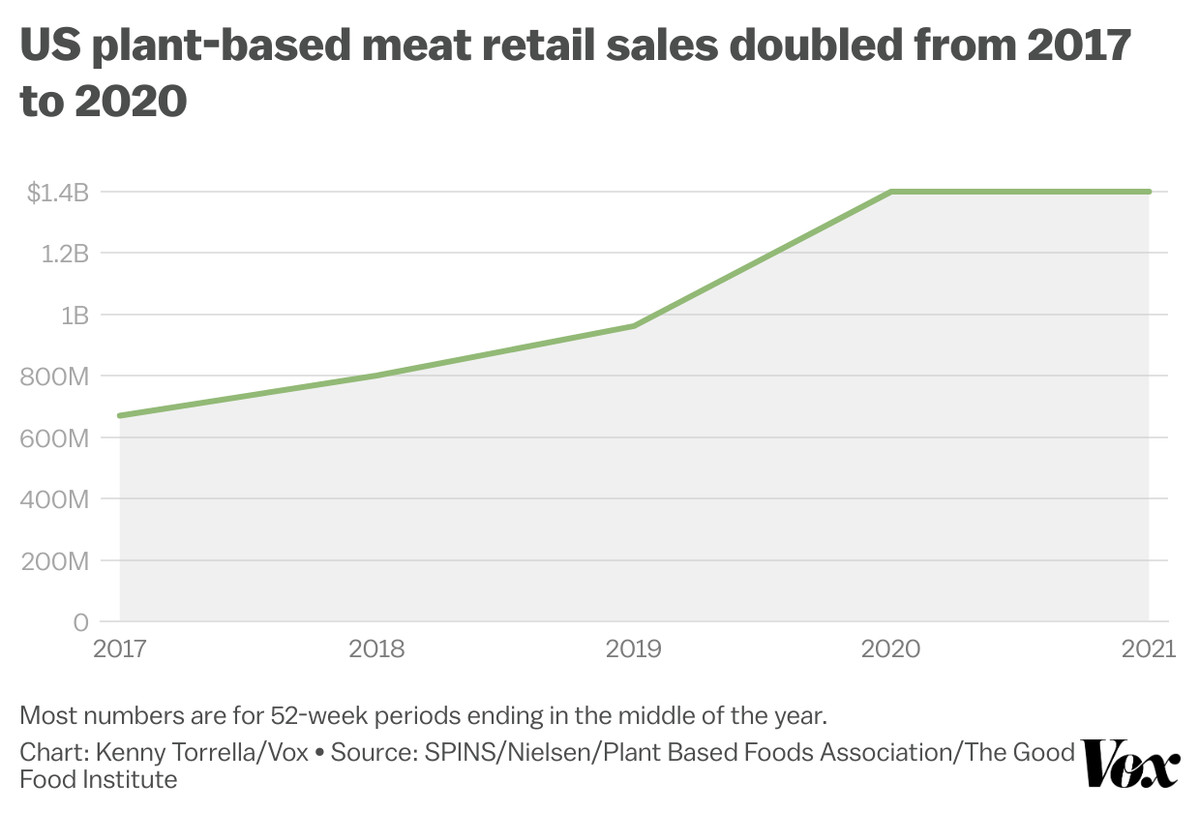

For years, sales of plant-based meat grew at a rapid clip. But in 2021, that growth stalled. That’s partly because the growth in 2020 was unusual — the pandemic, and all the panic-buying it induced, sent all grocery sales to the moon, plant-based meat included.

But now, repeat purchase rates are lower than companies anticipated. Maple Leaf Foods, a big plant-based meat (and animal meat) producer in Canada, walked back some of its ambitious plans to scale up plant-based meat production after lagging sales, and Bloomberg has reported disappointing trials of veggie burgers at fast food chains.

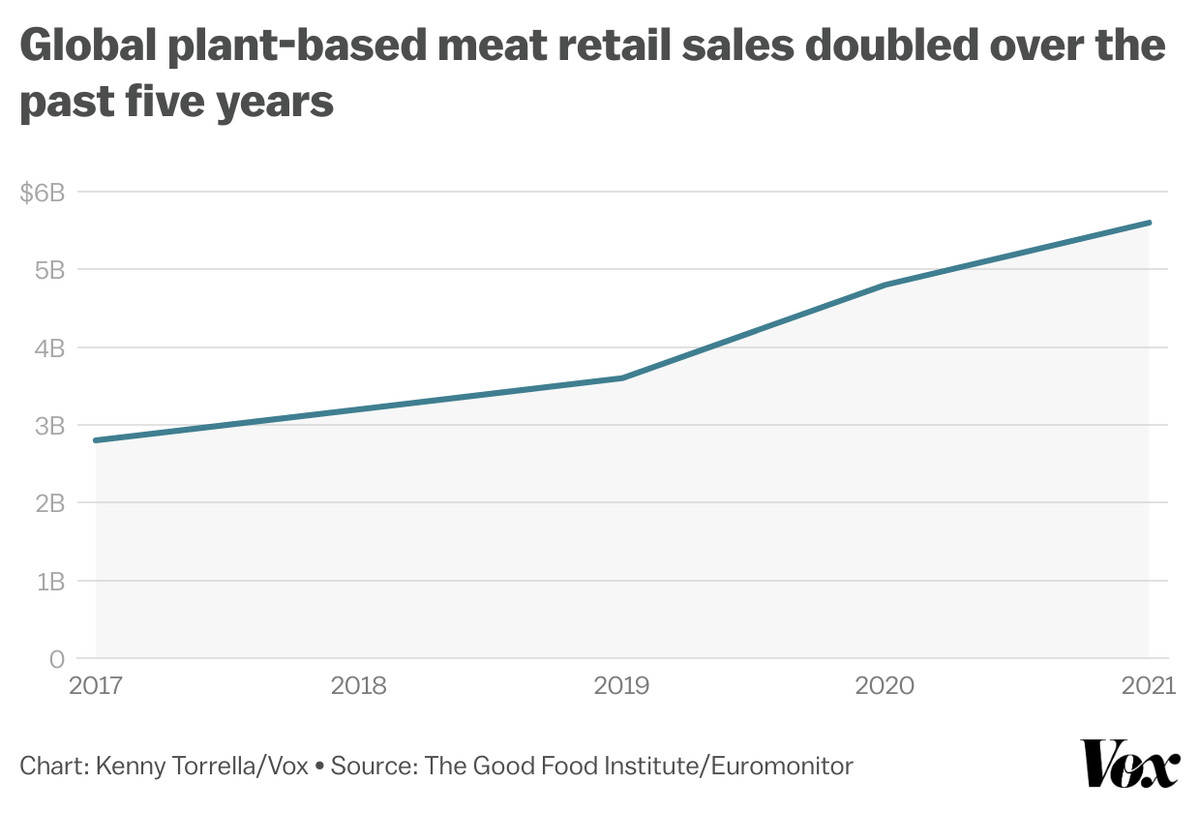

But the global outlook for plant-based meat alternatives appears rosier than North America’s.

A lot of the noise about the plant-based meat market comes out of the US, where some of its biggest companies are headquartered. But Asia and Europe are also major producers and consumers of meat alternatives.

According to an analysis from the Good Food Institute, using data from market research firm Euromonitor, grocery sales of plant-based meat are estimated to have doubled around the world from 2017 to 2021.

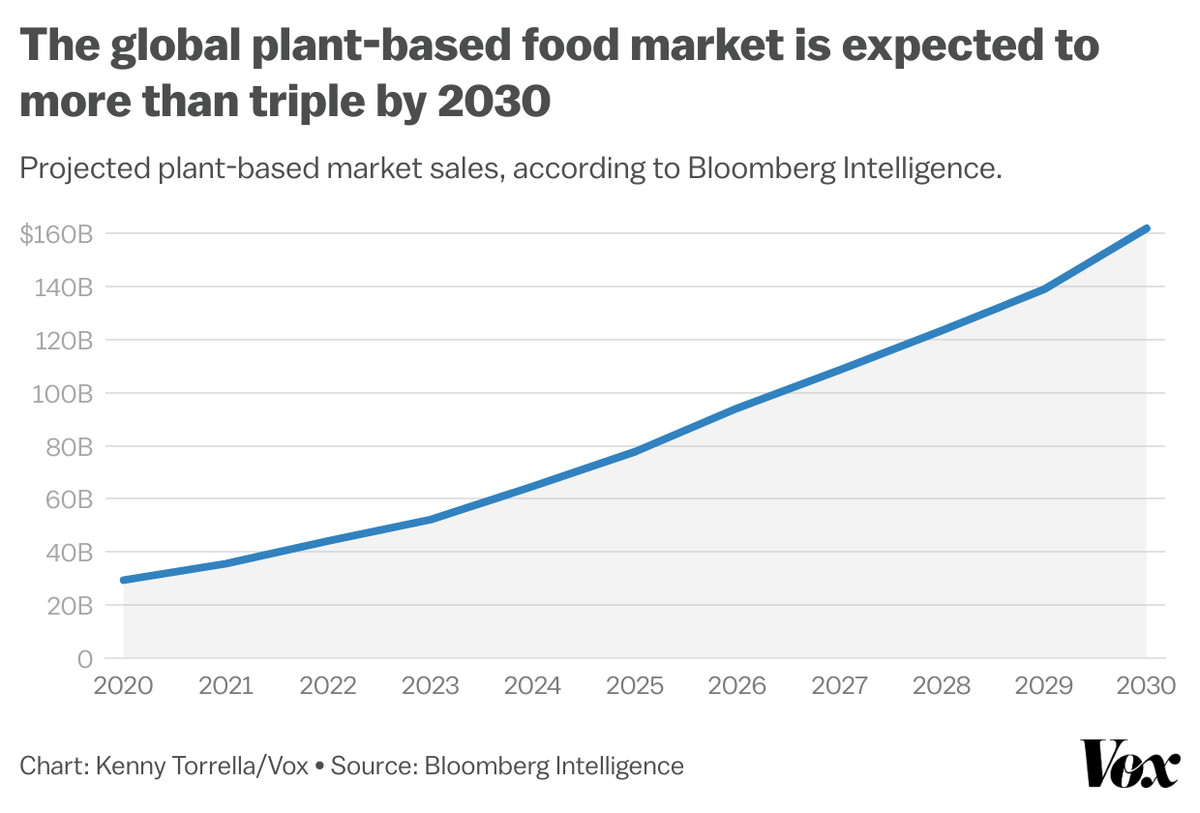

The growth is expected to steadily continue. Bloomberg Intelligence is forecasting global plant-based food sales to more than triple from 2022 to 2030.

The meat and milk alternatives industry hasn’t made a dent in displacing conventional animal agriculture, but it’s still quite young. Advocates for a more humane food system aren’t putting all their eggs in that basket, though, and have been steadily working toward regulations that make factory farming a little less awful.

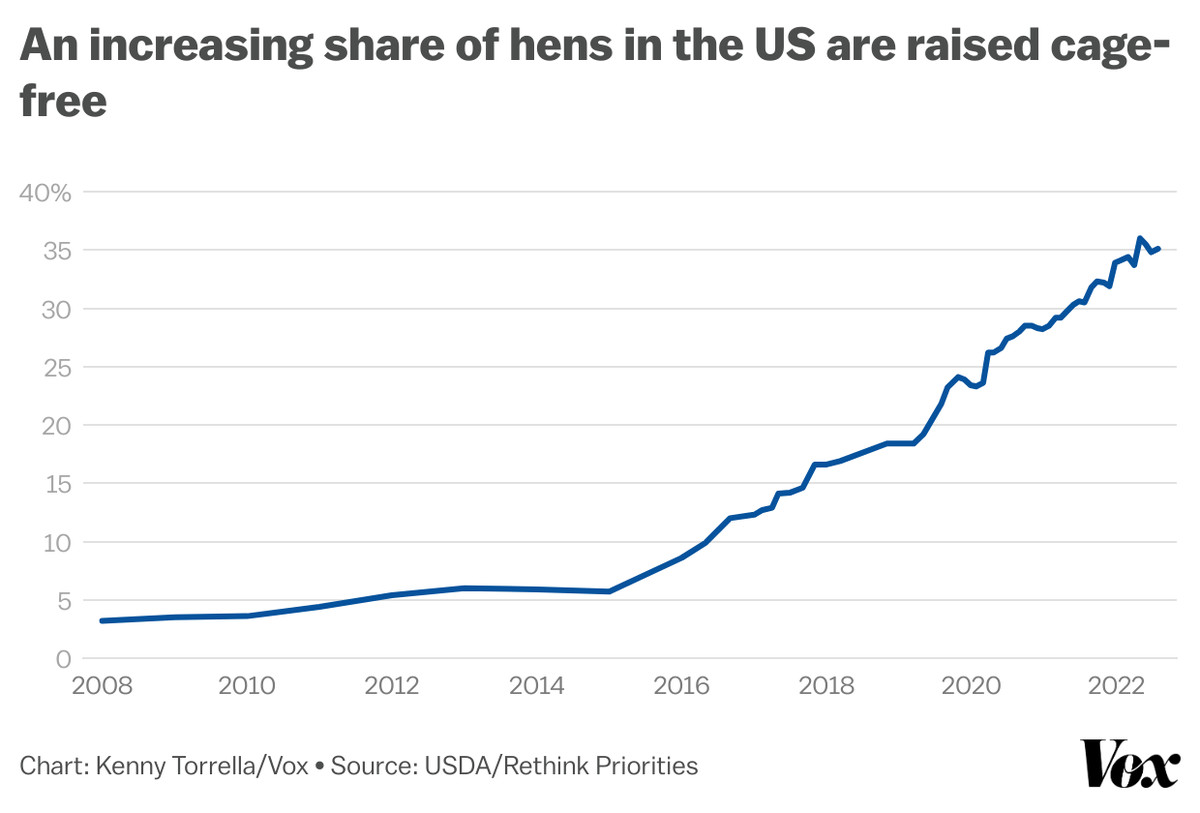

The US egg market looks a lot different today than it did at the start of 2015. Back then, only about 6 percent of hens raised for eggs were cage-free. The rest suffered miserably in what the industry calls battery cages, where each hen is given less space than a sheet of paper. They’re forced to live that way for 1 or 2 years until their productivity wanes and they’re turned into soup stock, animal feed, or pet food.

But in 2015, a California law that bans cages for hens went into effect. Big food companies, like Panera Bread and Starbucks, started sourcing more and more cage-free eggs following pressure from activists. Then more states banned cages and more companies moved on the issue, creating a virtuous cycle. Now 35 percent of hens in the US are cage-free, showing that progress can be made on the welfare side of things, and that it can happen quickly.

Still, it will be important to keep an eye on a pending case in the Supreme Court about another California animal welfare law that bans the use of crates for female breeding pigs — if it’s struck down, it could have lasting negative effects on efforts to improve farm animal welfare in the US.

A word of caution: Cage-free, while superior to conventional farming practices for the chickens’ welfare, does not equate to cruelty-free. Most cage-free hens never have access to the outdoors. Many still die prematurely from disease. They live in their own waste in cramped barns. But it’s progress nonetheless, and that progress has moved even faster across the Atlantic.

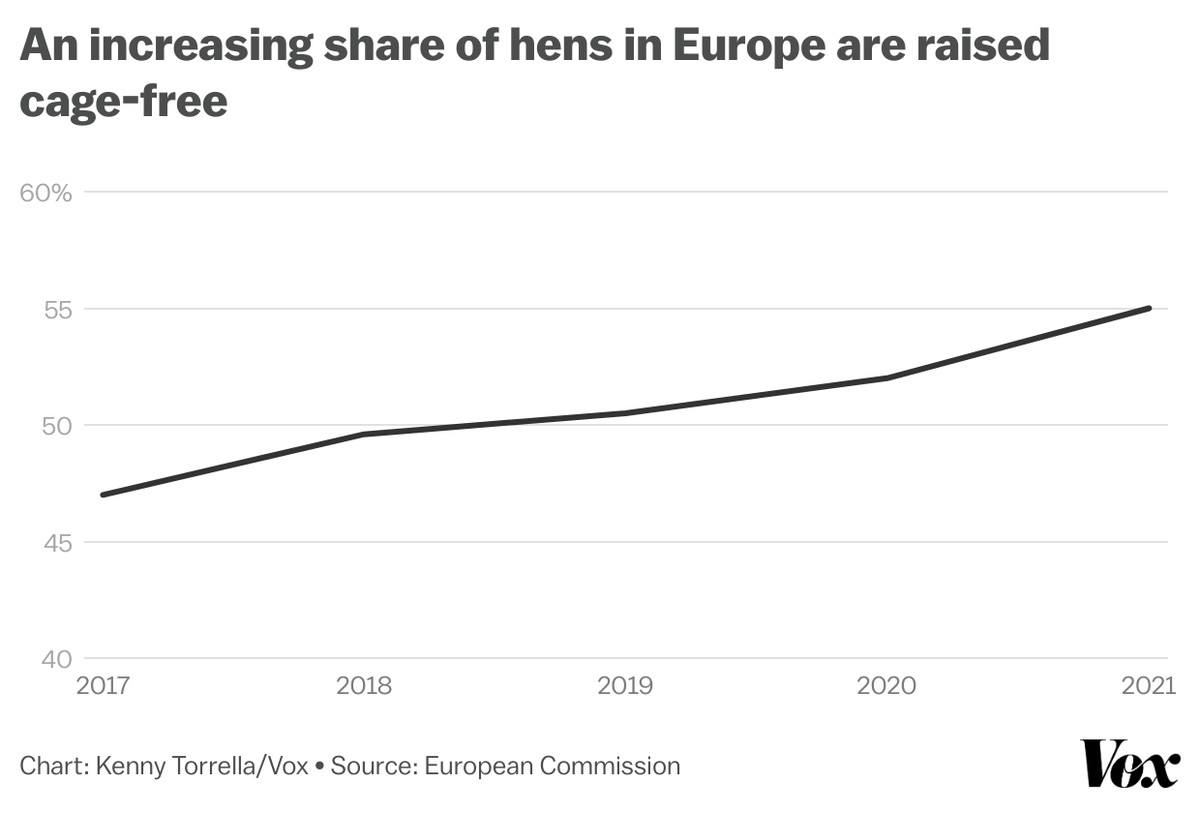

Some of Europe’s biggest countries have a majority of cage-free hens, like Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy. The rest of the continent is catching up; in 2017, 47 percent of hens were out of cages, and by 2021, it had risen to 55 percent. That equates to millions fewer hens in cages over the last few years.

And the effort might accelerate over the next decade. From Vox contributor Jonathan Moens:

The European Commission — the executive branch of the European Union — announced in June [2021] a ban on cages for a number of animals, including egg-laying hens, female breeding pigs, calves raised for veal, rabbits, ducks, and geese, by 2027. The plan would cover hundreds of millions of farmed animals raised in 27 countries. It puts Europe on track to implement the world’s most progressive animal welfare reforms within the decade. If ultimately enacted, it could turn out to be a pivot point in the decades-long fight to ease animal suffering.

There’s no doubt that the spread of factory farming across the globe, and the rise in meat consumption in lower-income countries, erodes the effects of many changes afoot in Europe and the US, as developing nations try to catch up with Western lifestyles.

But there is also strong public support for farm animal welfare across low, middle, and high-income countries, and there are budding animal advocacy movements and plant-based food startups sprouting up across the Global South, all trying to head off what could be a looming tsunami of industrialized meat production on the horizon.