Apple, under fire from developers and regulators about the way it runs its powerful App Store, is changing some of its rules, via a proposed lawsuit settlement.

Is that a big deal or a nothingburger?

Depends on who you ask. Apple says it’s giving companies like Spotify and Epic Games, the developer behind Fortnite, something they have always asked for. Those companies and other tech critics say it’s not nearly enough.

And some of the early press coverage of the news is all over the place. “Apple will let developers accept payment outside App Store, in major concession amid antitrust pressure,” the Washington Post incorrectly reported last night. New headline today: “Apple loosens rules for developers in major concession amid antitrust pressure.”

And the real answer is … this is somewhere in between a big deal and a nothingburger.

But the real story is that scrutiny over the way Apple runs its store, and whether it is preventing companies from offering real competition to both the App Store and Apple-owned services like Apple Music, isn’t going away. If you’re an Apple user who only cares about how much you have to pay for something like Spotify, this might be of interest to you.

And if you’re someone who cares about the power of Big Tech companies to set rules that affect millions of people around the world, it’s also worth watching.

Here’s a quick version of the news: Late Thursday night, Apple announced an agreement with attorneys in a class action lawsuit filed by software developers, promising to “make the App Store an even better business opportunity for developers, while maintaining the safe and trusted marketplace users love.”

There are several elements to the proposed deal — which still needs to be approved by a federal judge — but the most important one is that Apple is giving developers the ability to email customers who use their apps on Apple’s iOS devices, and tell them that they can save money by paying for stuff somewhere other than Apple apps.

The reason that’s meaningful is that up until now Apple, which takes a cut of up to 30 percent of any money developers generate when they sell something via an Apple app, hasn’t allowed developers to tell customers about cheaper alternatives. Now they can.

So Spotify, for instance, could sell a monthly subscription to its streaming service for $13 via an Apple app — but could then immediately email someone who signed up for that service to tell them they could get the same thing for $10 a month if they signed up on Spotify.com.

So now Spotify, which has lodged an antitrust complaint against Apple with the European Union, and Epic, which has sued Apple for antitrust violations in the US, are getting some of what they want: the ability to tell their own customers they can go somewhere else.

But this settlement doesn’t mollify either company. They are pressing forward with their legal campaigns, for multiple reasons: Both of them, for instance, want to be much more direct about how they tell customers they can go somewhere else, by telling them in the app.

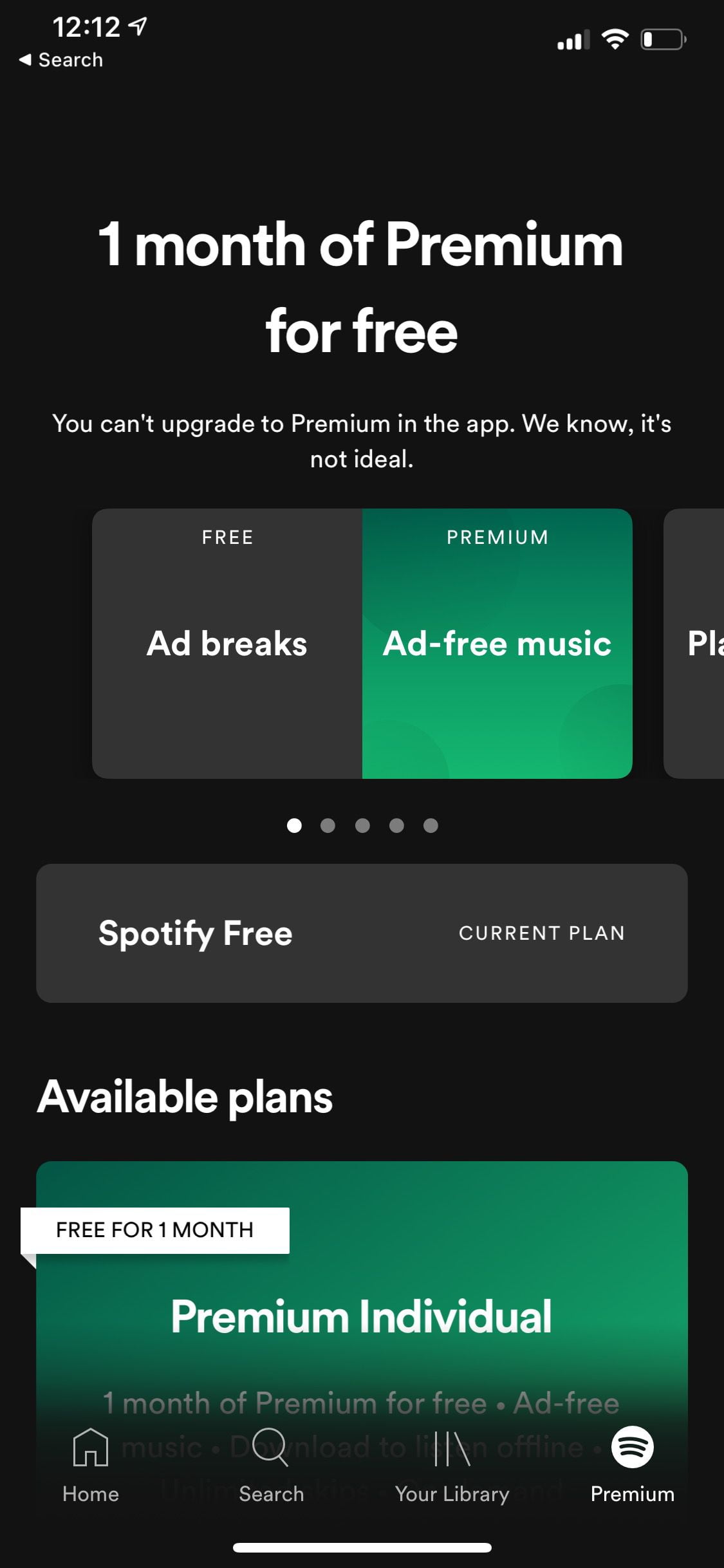

Right now, for instance, if you’re an iPhone user who wants to upgrade your free Spotify service to a paid one, Spotify simply tells you that you can’t do that on your app, without any other instructions about how to actually accomplish it. “We know. It’s not ideal,” the service shrugs.

But Spotify’s beef with Apple goes beyond how it can advertise. A major portion of the music service’s complaint is that it has to compete at a significant disadvantage with Apple’s own streaming music service because Apple doesn’t have to pay an App Store tax on its own services.

Epic, meanwhile, wants much more than the ability to steer customers to its own site. It says it wants to run its own app store within Apple’s App Store – and then, eventually, to run its own, competing app store. And Apple wants no part of that.

Meanwhile, other critics argue that even Apple’s email concession may not be that meaningful since it requires developers and users to take a lot of extra steps. Just getting someone to open up a promotional email requires a lot of effort these days; think of your inbox and how much clutter you routinely ignore.

If you’re an Apple advocate, meanwhile, you can argue that developers should be happy with any concession Apple offers because it’s Apple’s store and Apple’s devices and Apple should be able to do what it wants on its own property. If you go to a Walmart, for instance, you won’t find signs saying you can buy Tide for less at Target or Amazon.

Or, more charitably: You can argue that Apple’s App Store has provided developers with a huge market of iPhone and iPad users — “an economic miracle,” as Apple executive Phil Schiller puts it in the Apple press release — and letting Apple set up rules around its own store seems like a reasonable trade.

All of this debate underscores just how much pressure Apple is now under from both developers and regulators, which is quite new. Apple’s App Store was a literal afterthought — it didn’t show up until a year after the iPhone’s 2007 debut — but has evolved over the years into a major distribution funnel for developers, and a real profit center for Apple, likely generating $15 billion in revenue last year. And developers have complained about App store rules for at least a decade.

But Apple didn’t feel any pressure to move on any of this until very recently. Now, though, as regulators and politicians talk about reining in Big Tech in general, they’ve spent some of their time focused on Apple and its store, and whether the company’s rules are too rigid and anticompetitive.

EU regulators have already said they think Apple is violating antitrust rules, though they haven’t made a final ruling. Sen. Amy Klobuchar has made Apple a prime target in her antitrust arguments — she’s co-sponsored a bill that would limit the way both Apple and Google run their app stores. Via her press office, she says last night’s changes won’t be enough:

“As mobile technologies have become essential to our daily lives, it has become clear that Apple, along with another few gatekeepers, have immense control over the app marketplace. This power raises serious competition concerns and impacts consumers and app developers alike. This new action by Apple is a small first step towards addressing some of these competition concerns, but more must be done to ensure an open, competitive mobile app marketplace, including commonsense legislation to set rules of the road for dominant app stores.”

State lawmakers, meanwhile, are ramping up their own challenges to Apple’s rules, and the Biden White House seems very interested in pushing back on Big Tech’s power in general.

Which means this is unlikely to be the last App Store concession Apple has to make. Whether it continues to make incremental changes or makes big sweeping ones will tell us a lot about how motivated and effective Big Tech critics are going to be.