A long time ago, I got some prime email real estate: saramorrison@gmail.com. No middle initial, no extra numbers at the end. Clean, simple, easy to remember. I was truly blessed.

Today, Gmail is the most popular email service in the world, which has created a seemingly limitless number of what I collectively refer to as the Other Sara Morrisons: people who share my name and who, for whatever reason, enter my Gmail address when they mean to use their own. Their frequent invasions of my inbox have made me realize how much trust many of us put in a system that wasn’t designed to do some of the things we’ve come to use it for.

Email isn’t just a communication tool; it’s also an identifier and a security measure. Companies use it to create profiles of you when you start accounts with them and it often doubles as your username. Your email can also serve as your account recovery tool when you forget your username or password. All of this from something that doesn’t require you to verify your ID and that most people get to use for free, provided by a giant corporation that wants to harvest our data. In premium email provider Hey’s words, email is the “skeleton key to your digital life.” Well, I have a skeleton key to a lot of other people’s digital lives, too.

Emails sent to me that were meant for Other Sara Morrisons have given me a good deal of insight into — and a disturbing amount of access to — the lives of the many people who share my name. I know when and where their medical appointments are. I know when they give birth and am kept apprised about what their child ate and how often she pooped at daycare. I know when and where they’re going on vacation, what car they’re renting, and I get tickets to the theme parks they’ll visit when they get there. I’ve been part of a monthslong job hunting process for one Other Sara Morrison and received the renewed occupational license for another … twice. I know their property tax payment issues. I know their addresses. I know their credit card numbers.

“Having email be your unique identifier has been such a bad idea for such a long time,” said Honan, whose relatively common name and email domain means he, too, gets “weird, misdirected stuff all the time,” including many emails related to a social networking site for doctors he believes his address was erroneously signed up for several years ago.

“It’s just completely preposterous to me that it is still used in that way,” he added. “It’s obviously so fraught and so easy to send the wrong stuff to the wrong people.”

The surprisingly long history of email

Table of Contents

Despite decades of pronouncements that email is dead, it is very much alive. Technology research firm Radicati Group estimates that 4.1 billion users worldwide send 319 billion emails every day.

“For all of its flaws, email is still, by most measures, the most effective communication tool ever devised in human history,” Andy Yen, CEO of ProtonMail, told me. “It’s one thing that everybody has.”

And it’s been around for longer than you might think. The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), a branch of the Defense Department, created a precursor to the internet in the 1960s by remotely connecting computers in order to exchange data. It didn’t take long to realize that this network could also be used to send messages to the people who used those computers.

“It wasn’t as if somebody began by saying, ‘What we need is a means for secure messaging, some basic transmission, and that ought to have secure identification of sender and recipient.’ That wasn’t part of the equation,” Paul Duguid, a professor at the University of California Berkeley who studies the history of information, told me. “I think we’re still living, to some extent, with the consequences of that.”

Duguid added that while he couldn’t quite relate to my particular problem (there aren’t many Other Paul Duguids in the world), he was sympathetic.

Ray Tomlinson is widely credited as the inventor of email, but the technology evolved in a piecemeal fashion, over time, with additions and improvements from a lot of people. Dave Crocker worked on an early effort to create email standards in 1977 and spent the rest of his career creating or contributing to internet mail standards, which he is still doing today. Crocker told me that email was the result of a “massive amount of increments,” most of which were reactive; each iteration was a solution to an existing problem, or someone just coming up with “a cool idea.”

“These have typically not been orchestrated in a way you’d call planning,” he said.

By the end of the ’70s, email was pretty similar to what it is today in form and function, and a small but unamused list of recipients had received the first known spam email — an early sign of its potential for abuse. But when the internet was only accessible to a small community, even the rare instance like that was on a small and manageable scale. Crocker, who said he occasionally gets emails meant for Other D. Crockers, including a particularly troublesome repeat offender in Wales, compared the scenario to a small town where no one locks their doors.

“It’s not that there was no concern for security, it’s that it didn’t have quite the same concerns,” he said. “And then the internet blew up into the global service that it is now.”

So did email. In 1983, MCI began a service that let its customers communicate with each other electronically at the low, low price of $1 per 1,000-word message.

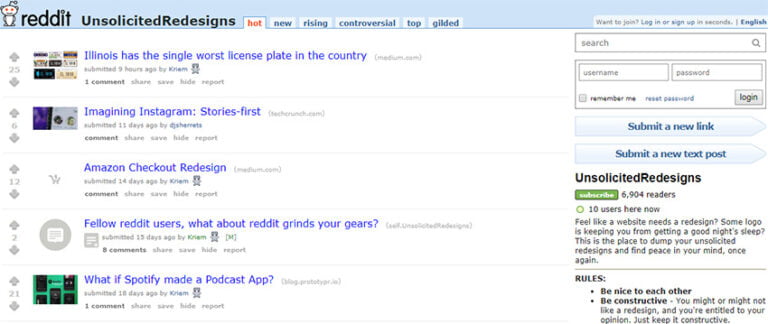

[embedded content]

As more people got personal computers for their homes, subscription-based, closed online networks like Compuserve, Prodigy, and AOL grew in popularity. Those were how most consumers — millions of them by the early ’90s — got online and where they got their email addresses. When email was provided to you by a service you dialed into from a telephone number and paid for with a credit card, whatever you did with that email could easily be tied back to you by its provider. Which is why, when I “broke the rules” and “caused a significant disturbance” in the Homework Helpline chatroom, AOL could attribute that to my parents’ account and ban my entire family. And back then, if you canceled or otherwise lost your access to your AOL account, you lost your email address, too.

That’s not the case anymore. The invention of the World Wide Web in 1989 and free web browsers to navigate it meant that people could get their email addresses through websites, rather than paid online services. This began with Hotmail, which was released in 1996. It was free and browser-based, so you could log into your Hotmail account from any internet connection and you didn’t have to provide any identifying information to anyone to get it. Yahoo launched its own browser-based email service soon after. Hundreds of millions of people around the world had email addresses by the end of the century.

Gmail showed up in 2004. Like its competitors, it was free and ad-supported. Unlike them, it scanned users’ emails to better target ads to them, a practice it only stopped in 2017. By 2012, Gmail was the most popular email service out there. Google wouldn’t give me any user numbers (nor would it comment for this story), but it tweeted in 2018 that it had 1.5 billion of them.

All of this means that what has become a hugely important part of our lives is built on a decentralized system of suggested standards and protocols that is owned by no one but is largely operated by a few of the biggest companies in the world. Email is also a major vector for cyberattacks (even presidential campaigns are not immune). If people and companies don’t take the right precautions, their security can be compromised by clicking on the wrong link or making a simple typo.

“We have to face the fact that this is a problem that’s been brewing for decades,” Marc Rogers, executive director of cybersecurity at Okta, an identity authentication technology company, told me. “Email was not designed to be a secure medium.”

And while Rogers says that some of the blame for this rests on the people who don’t type their email addresses carefully, the bulk of the responsibility is on companies that send those emails.

“They need to realize that email should not be used for sensitive activity unless they’ve taken steps to prove they know who’s ‘residing’ there,” he said. “You have to prove who controls that email.”

And yet, you don’t have to prove anything to get that email in the first place. I’ve had that Gmail address longer than I’ve had any one physical address in my adult life, or any phone number or any driver’s license number. The only identifier I’ve had for longer is my Social Security number. I got that from the federal government after my parents submitted proof of my identity and citizenship status. I just had to fill out a few prompts on a website to get my email address.

My futile attempts to escape the Other Sara Morrisons

As I’ve become more aware of my online identity and its vulnerabilities (getting hacked and almost losing $13,000 will do that to you), I’ve been trying to cull my accounts, only for a parade of Other Sara Morrisons to sign me up for many more. Removing my email from them isn’t easy.

Here’s an example:

One Other Sara Morrison ordered three pairs of mid-rise capri pants from J.C. Penney. She accidentally used my email address for her new J.C. Penney Rewards account. J.C. Penney’s website didn’t give me a way to delete my email from the account, so I did it through Twitter DMs, where the company made me provide the phone number and physical address on Other Sara Morrison’s account — I had to log into her account to get that. While looking for the required information, I saw her credit card number, which she had saved to make future purchases fast and easy.

This all seemed pretty bad, so I asked J.C. Penney why it didn’t have an email verification system or an easy way to change email addresses on accounts. J.C. Penney declined to comment. J.C. Penney’s Twitter account assured me that it deleted my address from Other Sara Morrison’s Rewards account. Two months later, I received a fleet of emails tracing the journey of the five V-neck T-shirts she just ordered.

Some places do have laws that give you the right to demand that companies delete your data. But they don’t apply where I live, so all I can do is be envious of my friends who live in states like California and countries in Europe and have rights I don’t.

Meanwhile, most of the Other Sara Morrisons have no idea that their accounts are compromised, and I can’t tell them because the only contact information I have is the email address they supplied — which is mine.

Can email be fixed?

In the process of reporting this article, I realized how casually and even haphazardly I’ve treated email. Years ago, I got a free email account from a company known for its search engine. It served my basic needs so it didn’t occur to me to change it, even as that search engine company — and email itself — became so much more.

Some of the experts I spoke to suggested starting fresh with a new email address and using this as a chance to think about what I wanted out of my email experience — a remodel of my digital home, if you will. There are other email services out there, some of which have features that those major consumer email services don’t. A couple examples are ProtonMail and Hey. ProtonMail’s selling point is its privacy and security. Emails are end-to-end encrypted, so even Proton can’t access their contents (which means the government can’t get anything from the company, either). Meanwhile, Hey’s mission is to make your email experience more pleasant and customizable, and to give users greater control over whose emails they receive and whose they reject.

Even Big Tech companies are trying to sell an improved email experience. Apple now lets you conceal your iCloud email address when you sign up for accounts and newsletters, which gives you more control over who knows your email address.

But all of these features come at a cost. ProtonMail’s basic service is free but limited, with more features and storage space for paid accounts starting at $5 a month or $48 a year. Hey’s email service starts at $99 a year. You have to have an Apple device to have an iCloud email address, and some of Apple’s new email features require an iCloud subscription, which starts at 99 cents a month.

But most of us have been using free email providers for our personal addresses for decades and don’t think or care about the trade-offs we’ve made for them. Will people really want to pay for email? The founders of ProtonMail and Hey think the answer is yes, saying that more people want to preserve their privacy and avoid Big Tech than ever before. Yen, of ProtonMail, said his service has 50 million users, though most of them use the free version. David Heinemeier Hansson, of Hey, said the company amassed 30,000 paid users in its first three months.

Most email providers will let you use your personal domain with their email services, so you don’t have to choose between, say, ProtonMail’s privacy protections and having your own domain address. If you don’t want to leave Google, you can even use Gmail with an address from your own domain. You can have the best of both worlds, as long as you can pay for them.

I have given up

Perhaps there will, one day, be a new type of identifier that doesn’t have email’s flaws but is just as ubiquitous. Crocker said there’s probably some effort out there involving blockchains — “there’s almost always an effort involving blockchains for almost anything.” Some companies are starting to incorporate biometrics into their identity authentication systems. Companies like Rogers’ Okta offer single sign-on services that verify users without passwords. But it’s hard to believe they’ll have the widespread adoption of email anytime soon.

“Email addresses just keep plodding on and on being useful,” Crocker said.

Email really is an amazing, miraculous technology. But at the end of the day, it’s in the hands of humans who are always going to screw it up. If you have a common name and an email domain that’s used by billions of people, you’re going to be on the receiving end of a lot of those screw-ups for the foreseeable future. There doesn’t seem to be a way to both keep my Gmail address and avoid the Other Sara Morrisons’ incursions. I wasn’t sure if it was worth the hassle of switching everything over to a new email address just to get rid of them.

But then ten Oever asked me: “Do we really want the world’s biggest post office to be run by an American corporation?” No, I didn’t.

On this journey, I’ve come to realize that saramorrison@gmail.com never truly belonged to me, to one Sara Morrison. It belonged to Google. But also, in a greater and more philosophical sense, it belonged to all Sara Morrisons. And so it belonged to no one.

I cede it back to the digital ground from which it came. The inbox will lie fallow, collecting whatever email seeds happen to drift its way, take root, and grow. It will become a jungle of newsletters, password resets, and order confirmations — intertwined, unabated, unread, and reclaimed by the virtual Earth.

I will build a new home somewhere else. The Other Sara Morrisons are not invited.