If you got a Covid-19 test at Walgreens, your personal data — including your name, date of birth, gender identity, phone number, address, and email — was left on the open web for potentially anyone to see and for the multiple ad trackers on Walgreens’ site to collect. In some cases, even the results of these tests could be gleaned from that data.

The data exposure potentially affects millions of people who used — or continue to use — Walgreens’ Covid-19 testing services over the course of the pandemic.

Multiple security experts told Recode that the vulnerabilities found on the site are basic issues that the website of one of the largest pharmacy chains in the United States should have known to avoid. Walgreens has promoted itself as a “vital partner in testing,” and the company is reimbursed for those tests by insurance companies and the government.

Alejandro Ruiz, a consultant with Interstitial Technology PBC, discovered the issues in March after a family member got a Covid-19 test. He says he contacted Walgreens over email, phone, and through the website’s security form. The company was not responsive, he says, which didn’t surprise him.

“Any company that made such basic errors in an app that handles health care data is one that does not take security seriously,” Ruiz said.

Recode informed Walgreens of Ruiz’s findings, which were confirmed by two other security experts. Recode gave Walgreens time to fix the vulnerabilities before publishing, but Walgreens did not do so.

“We regularly review and incorporate additional security enhancements when deemed either necessary or appropriate,” the company told Recode.

People’s sensitive data could be exposed to numerous ad and data companies to use for their own purposes, or they may be discouraged from getting a Covid-19 test from Walgreens if they aren’t confident that their data will be secure. The platform’s vulnerabilities are also another example of how technology meant to assist in the effort to stop the pandemic was built or implemented too quickly and carelessly to fully take privacy and security into account.

Walgreens also wouldn’t say how long its testing registration platform has had these vulnerabilities. They go back at least as far as March, when Ruiz discovered them, and likely far longer than that. Walgreens has offered Covid-19 tests since April 2020, and the Wayback Machine, which keeps archives of the internet, shows blank test confirmation data pages as far back as July 2020, indicating that the issue dates back at least that far.

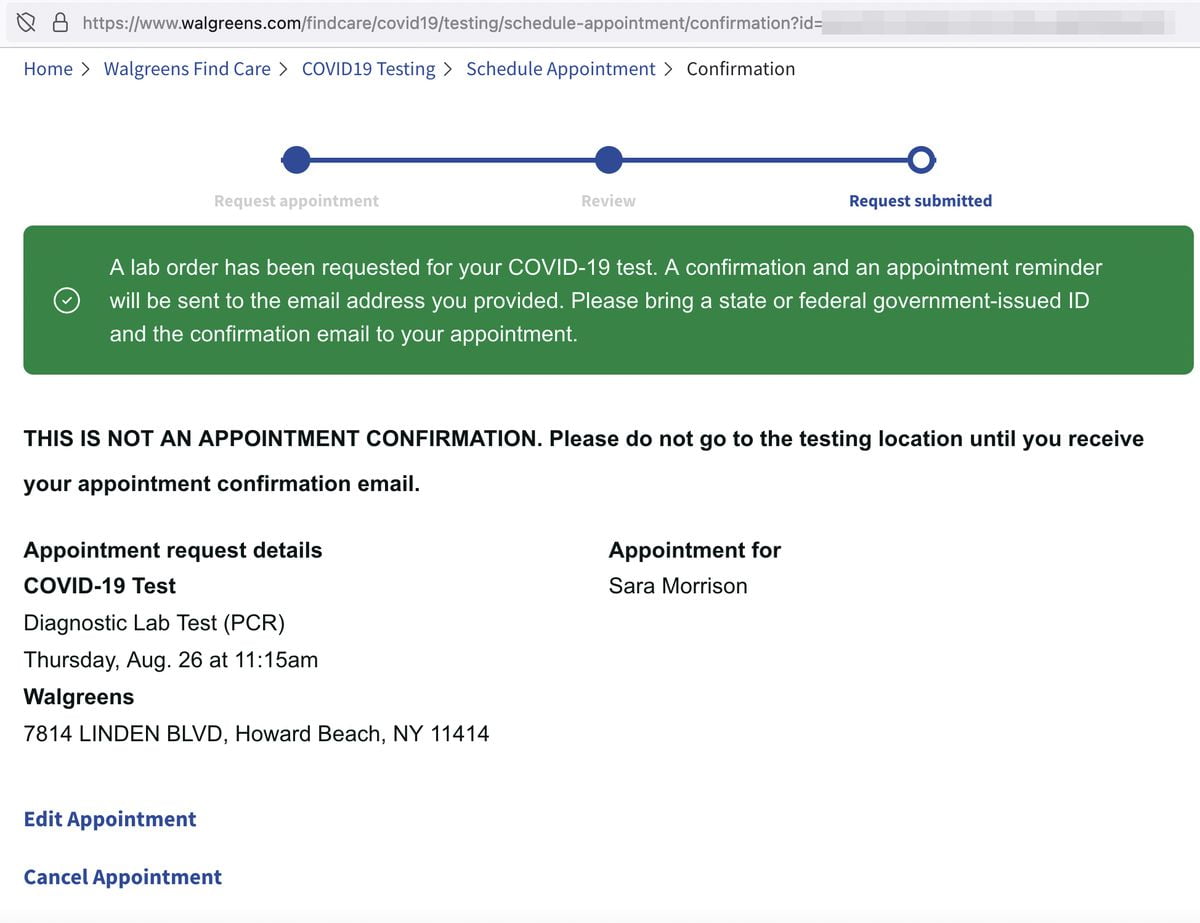

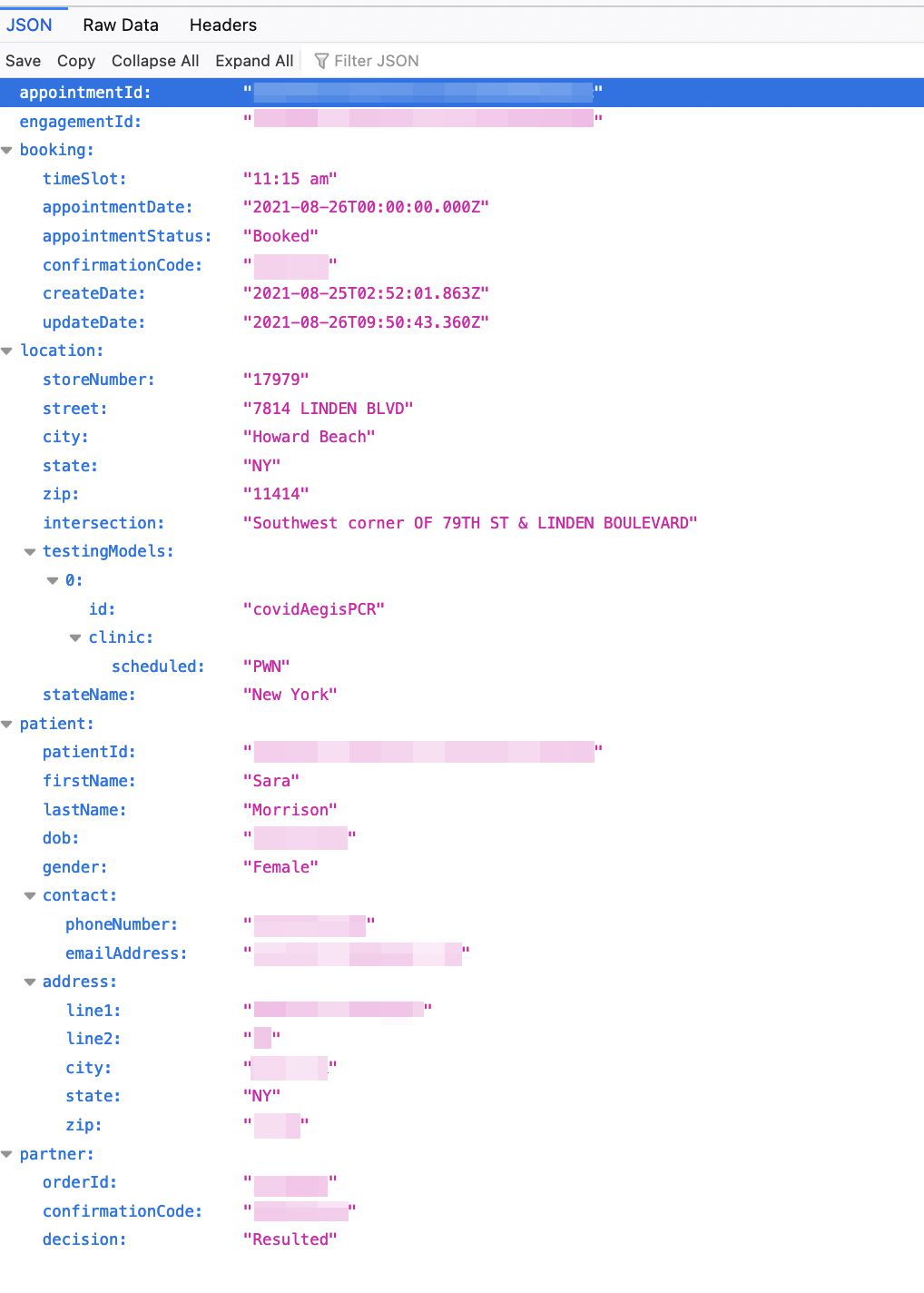

The problems are in Walgreens’ Covid-19 test appointment registration system, which anyone who wants to get a test from Walgreens must use (unless they purchase an over-the-counter test). After the patient fills out and submits the form, a unique 32-digit ID number is assigned to them and an appointment request page is created, which has the unique ID in the URL.

Anyone who has a link to that page can see the information on it; there’s no need to authenticate that they are the patient or log in to an account. The page remains active for at least six months, if not more.

“The technical process that Walgreens deployed to protect people’s sensitive information was nearly nonexistent,” Zach Edwards, privacy researcher and founder of the analytics firm Victory Medium, told Recode.

The URLs for these pages are the same except for a unique patient ID contained in what’s called a “query string” — the part of the URL that begins with a question mark. As millions of tests across more than 6,000 Walgreens testing sites were run using this registration system, there are likely millions of active IDs out there. An active ID could be guessed, or a determined hacker could create a bot that rapidly generated URLs in the hope of hitting any active pages, security experts told Recode, giving them a source of biographical data about people they could potentially use to hack their accounts on other sites. But, given how many characters are in the IDs and therefore how many combinations there are, they said it’d be close to impossible to find just one active page this way — even with the millions of them out there. Of course, close to impossible is not the same as impossible.

Anyone who has access to someone’s browsing history can also see the page. That might include an employer that logs employees’ internet activities, for example, or someone who accesses the browser history on a public or shared computer.

“Security by obscurity is an awful model for health records,” Sean O’Brien, the founder of Yale’s Privacy Lab, told Recode.

What makes this potential leak significantly worse is just how much data is stored on the website and who else could be getting access to it. Only the patient’s name, type of test, and appointment time and location are visible on the public-facing pages themselves, but far more than that is behind the scenes, accessible through any browser.

As it did with vaccine appointments, Walgreens requires a great deal of personal data to register for one of its tests: full name, date of birth, phone number, email address, mailing address, and gender identity. And with a few clicks in a browser’s developer tools panel, anyone with access to a specific patient’s page can find this information.

Included is an “orderId,” as well as the name of the lab that performed the test. That’s all the information someone would need to access the test results through at least one of Walgreens’ lab partners’ Covid-19 test results portals, though only results from the last 30 days were available when a Recode reporter looked hers up.

Ruiz and the other security experts Recode spoke to also expressed alarm at the number of trackers Walgreens placed on its confirmation pages. They flagged the possibility that the companies that own these trackers — including Adobe, Akami, Dotomi, Facebook, Google, InMoment, Monetate, as well as any of their data-sharing partners — could be ingesting the patient IDs, which could be used to figure out the URLs of the appointment pages and access the information they hold.

“Just the sheer number of third-party trackers attached to the appointment system is a problem, before you consider the sloppy setup,” Yale’s O’Brien said.

Analysis from Edwards, the privacy researcher, found that several of those companies were getting URIs, or Uniform Resource Identifiers, from the appointment pages. Those could then be used to access the patient data if the company receiving them were so inclined. He said this type of leak is similar to what he discovered on websites including Wish, Quibi, and JetBlue in April 2020 — but “much worse,” as only email addresses were leaked in those cases.

“This is either a purposeful ad tech data flow, which would be truly disappointing, or a colossal mistake that has been putting a huge portion of Walgreens customers at risk of data supply chain breaches,” Edwards said.

Walgreens told Recode that it was a “top priority” to protect its patients’ personal information, but that it also had to balance the need to secure information with making Covid-19 testing “as accessible as possible for individuals seeking a test.”

“We continually evaluate our technology solutions in order to provide safe, secure, and accessible digital services to our customers and patients,” Walgreens said.

Again, Walgreens did not fix the issues before the extended deadline Recode provided to the company, nor would it tell Recode if it planned to do so. It did not address Recode’s questions about the ad trackers except to say that its use of cookies is explained in its privacy policy. However, tracking through cookies was not the issue Recode and Ruiz identified to Walgreens, and the company didn’t comment further when this was explained to it.

“This is a clear-cut example [of this type of vulnerability], but with Covid data and tons of personally identifiable information,” Edwards said. “I’m shocked they are refuting this clear breach.”

Ruiz’s family member’s data, along with that of potentially millions of other patients, remains up today.

“It’s just another example of a large company that prioritizes its profits over our privacy,” he said.