Welcome to the age of billionaire biodiversity conservation.

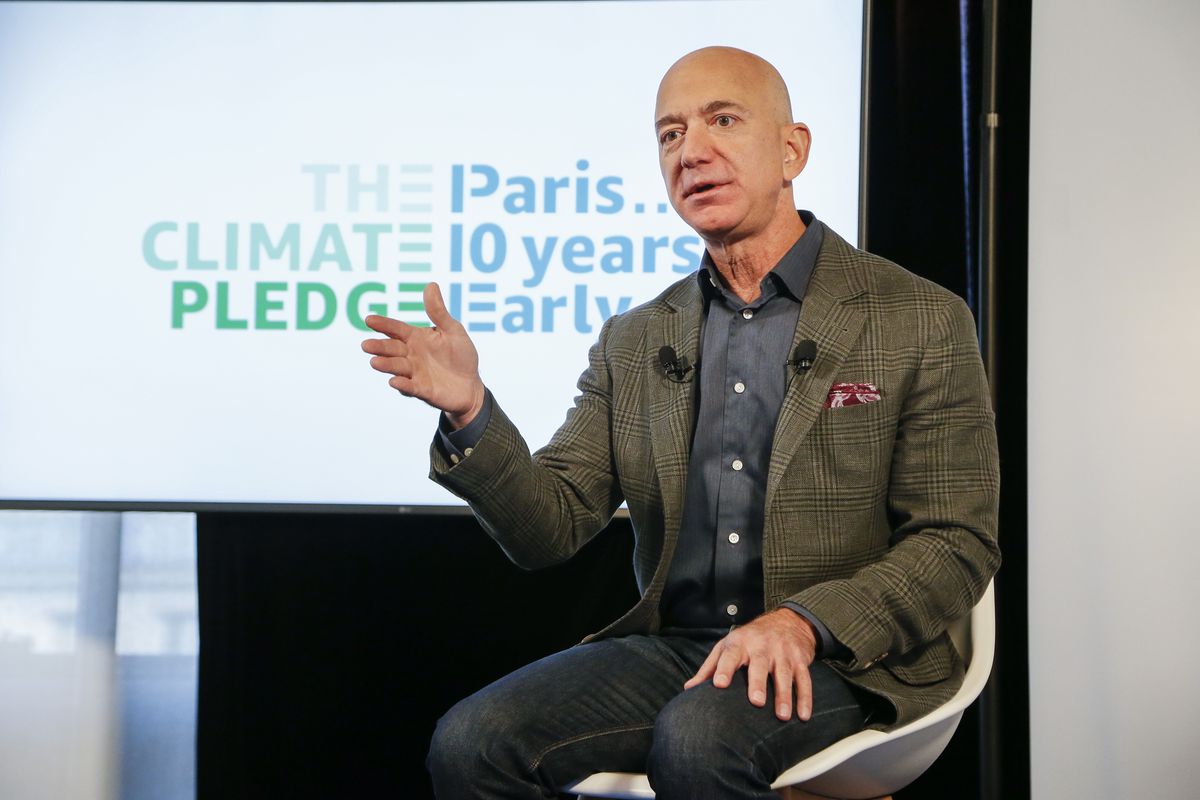

As climate change scorches the planet and a global extinction crisis escalates, the ultrarich have started funneling bits of their wealth into protecting nature. This week, Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and the wealthiest man on Earth, pledged $1 billion to protect land and water as part of his $10 billion Earth Fund.

Bezos was joined by eight other donors — including Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Rob and Melani Walton Foundation, which is built on the Walmart fortune — who together committed an additional $4 billion to the cause. Combined, it’s the largest private funding commitment ever to the conservation of biodiversity, which generally refers to diverse assemblages of species and functioning ecosystems.

In announcing the pledge, Bezos acknowledged that many past efforts to conserve nature haven’t worked. And he’s right, judging by the state of the environment: Populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish have declined by almost 70 percent on average since 1970, and the planet has lost about a third of its forests.

“I know that many conservation efforts have failed in the past,” Bezos said. “Top-down programs fail to include communities, they fail to include Indigenous people that live in the local area. We won’t make those same mistakes.”

Bezos and other billionaires are promising to support Indigenous-led initiatives, which represents something of a paradigm shift in conservation. But not all experts are convinced that their money will forge a new path and make a dent in the extinction crisis.

While Bezos is known for disrupting the e-commerce world, the primary approach his fund is taking — bolstering the planet’s network of protected and conserved areas — is not new, and could even be considered old-school. That’s not to say protected areas don’t work. They just don’t do much to erode the root causes of biodiversity loss, which include the very culture of over-consumption and same-day convenience that has made Amazon Amazon.

“Amazon remains reliant on massive fleets of polluting delivery vehicles, wasteful packaging, and even a new fleet of jet-fuel-powered planes to keep speedily delivering stuff to impatient online shoppers,” as Vox’s Rebecca Heilweil reported this week.

Which is to say: While Bezos and other billionaires are aiding conservation and signaling that their efforts will support a historically underfunded group of people, they’re doing little to limit the forces that make conservation necessary in the first place and that made them rich.

The age of billionaire biodiversity

Bezos’s announcement is just one of several recent pledges that have poured in from prominent billionaires — in support of biodiversity efforts like 30 by 30, which aims to protect 30 percent of all global land and oceans by 2030.

“Protecting at least 30 percent of our planet by 2030 is not a luxury but a vital measure to preserve the Earth’s health and well-being,” said Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, who run the UK-based Arcadia Fund, which is among nine philanthropy groups, including Bezos’s Earth Fund, that pledged the $5 billion to conservation this week.

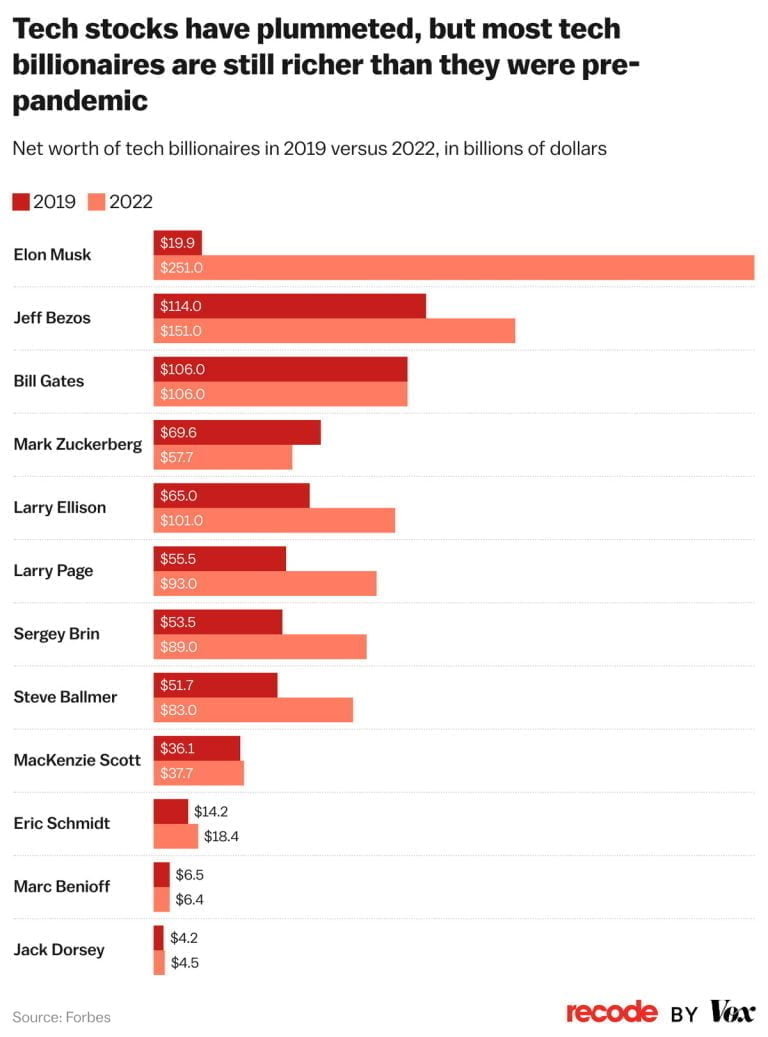

Other tech moguls have also thrown their weight behind conservation in recent years, from Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, who’s gone all-in on tree-planting, to Swiss billionaire Hansjörg Wyss, whose foundation put $1 billion into the 30 by 30 campaign. (The Wyss Foundation is also among the nine organizations that contributed to the $5 billion pledge.)

“We’re seeing a lot of [conservation funding] from billionaires, who are becoming increasingly conscious of the global cataclysm upon us,” said David Kaimowitz, a forestry director at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, who spent more than a decade at the Ford Foundation.

Plenty of good comes from big pledges like these: They draw attention to the biodiversity crisis — which is often overshadowed by other environmental concerns — and the fact that we can’t fight climate change without also protecting nature. The Earth Fund, after all, was set up to advance climate solutions.

Bezos’s pledge is “a really important gesture that we cannot solve the climate crisis without addressing biodiversity and conservation,” said Rachael Petersen, principal and founder of Earthrise Services, a consulting firm that advises high net-worth individuals and foundations on environmental philanthropy. “I think this will usher in climate donors who realize the importance of conservation as a climate strategy.”

It’s also meaningful that much of the recent funding from billionaires will, according to the donors, go toward supporting Indigenous people and local communities. “Five years ago, such a commitment would be unthinkable,” Kaimowitz said. “There has been a sea change in the global recognition of the central role of Indigenous peoples and local communities” in conservation, he said.

2019 biodiversity report, which raised the alarm about extinction threats. “If just throwing money at the problem solved the problem, we’d be farther along than where we are,” she said.

The bulk of recent pledges tend to favor somewhat traditional models of conservation, Dempsey said, such as building networks of protected areas or planting trees, which we’ve been doing for decades.

These kinds of initiatives are convenient because they work within established political and economic systems, Dempsey said — the very ones that allow billionaires to thrive. “Protected areas obviously can be extremely important,” she said. “But they don’t challenge existing concentrations of power and wealth.” A parallel might be fossil fuel companies investing in technologies that capture carbon: While those investments could reduce the greenhouse gases that are trapping heat in the atmosphere, they do nothing to disrupt the industries that spew climate-warming emissions.

Protected and conserved areas don’t, for example, address the issue of tax evasion, which limits the money that governments can spend on public conservation, Dempsey said. Bezos, like so many of the world’s ultrarich, pays barely any taxes relative to his wealth, which amounts to nearly $200 billion. “This works very well for someone like Bezos because he’s been a beneficiary of the structuring of our economy, which doesn’t tax wealth,” she said.

Traditional conservation funding also does nothing to lessen the waste created by corporations like Amazon, or the policies that enable them. The company’s carbon footprint has risen each year since 2018; last year, Amazon’s carbon emissions grew 19 percent, while global emissions fell roughly 7 percent, as Heilweil reported. What’s $1 billion — or even $5 billion — compared to the ecological harm that philanthropists’ companies have caused?

Another example of this uncomfortable juxtaposition comes from Norway, McElwee said. Much of the country’s enormous wealth stems from oil and gas production, yet Norway is also one of the world’s largest funders of forest conservation and clean energy. “Can we use capitalism to save the world from capitalism?” McElwee said.

Not in its current state, Dempsey said — unless the money from billionaires is spent on reining in their own power and influence, which is arguably antithetical to the very idea of capitalism. “You cannot have democratic approaches to any of these problems when you have that amount of concentrated wealth,” she said.

Where four experts would put $1 billion for conservation

So how should a person spend billions of dollars on biodiversity?

Dempsey recommends a “two-step” approach: Protect the environment, for example by creating more reserves or conserved areas (step one), while also fostering the political, economic, or social conditions for conservation strategies to succeed (step two).

On the conservation side, experts call for more investments in communities that already know and care for the land. “A very large percentage of the biodiversity left in the world is in areas managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities,” Kaimowitz said. “They’ve been able to manage these areas and protect these resources as well as — and, in many cases, better than — non-Indigenous protected areas.”

major driver of deforestation) or cleaning up corporate supply chains, instead of setting up a reserve for a rare species. “It’s easier to say, ‘We’re going to conserve X hectares of land,’” McElwee said, rather than try to fix a complex supply chain — and the companies that control it — that threatens a particular ecosystem.

Dempsey, meanwhile, would put money toward limiting the government policies that enable extractive industries, such as oil and gas, to become powerful. It should be more costly for banks and other financial institutions to lend to corporations that harm the environment, such as agribusinesses, she says. “We need to be thinking about how to rein in those flows in ways that don’t rely on voluntary measures or weak market disclosures,” she said.

We also need to fund politicians and policies that support Indigenous sovereignty, she said. There’s a limit to the impact of billionaires like Bezos if a country like Brazil — home to 60 percent of the actual Amazon, i.e. the world’s largest rainforest — doesn’t want Indigenous peoples to have autonomy and sovereignty over their resources, she said. It’s more complicated than simply saying that conservation efforts must be Indigenous-led, she added.

Similarly, McElwee wants to see more efforts directed at eliminating government incentives that benefit the oil and gas sector and other industries that harm the environment. “I would love to see a conservation organization have its mission be eliminating subsidies,” she said. “That is a perpetual issue that never seems to get solved. Maybe that will make it in your article and Bezos will read it and be, like, ‘Oh, I’m going to fund that.’”