Part 3 of our digital transformation series: why the greatest progress is often made by the smallest teams

We have found that creating small teams designed around a specific outcome ensures those teams are more productive and innovative.

Google Cloud

One of the greatest impediments to digital transformation efforts isn’t the lack of time, people, or budget–rather, it’s too many people.

The problem isn’t the small room or the fact that everyone wants to share their opinion. The problem is that your team is too big.

Google Cloud

When an organization faces a complex, novel problem, it can be tempting to throw lots of bright people at it. Add in a deadline, and the urge to create a big new “task force” or “working group” is bigger still.

Soon enough, you’ll find that everyone can’t fit in the same room, and that there isn’t enough time for everyone to speak up. The problem isn’t the small room or the fact that everyone wants to share their opinion. The problem is that your team is too big.

Selfishly, it makes sense for people to want to be involved in these high-profile projects. More people = parallel problem-solving, and getting things done faster—right? But when this happens, sharing knowledge and coordination becomes harder, not easier. Unless you can break the work into truly independent parts, adding more people can actually slow things down.

Digital transformation is as much about executing efficiently as it is about learning and iterating quickly.

In our experience working with customers on digital transformation projects, smaller teams have a clearer line of sight to the team goals, with more opportunities to be heard, and can often be more productive and innovative, for example, overcoming social loafing or taking advantage of the Köhler effect. Digital transformation is as much about executing efficiently as it is about learning and iterating quickly. Both ambitions degrade as you add more people and, by extension, more handoff points to the mix.

So how do you keep your digital transformation team small? Start with your desired outcome and form a team around that outcome. (Management consultants sometimes refer to this as an inverse Conway maneuver.) For example, your outcome may be to create a new software service (an API, a website, an app) or to provide a new technology platform such as Google Cloud Platform on which to run those services. Such a team will be situated in close physical (and/or virtual) proximity and will comprise different roles, ranging from requirements gathering and user interface design to software engineering, testing, and operations. Crucially, this team does not outsource key functions to other teams, e.g. a design team or a database team or an operations team.

What is the minimum number of individuals required to produce the desired outcome in a timely manner? Can you count them on two hands? Good! Is it more than ten? Not so good. Chances are the team’s cognitive load will be too high and members will spend a disproportionate amount of time communicating and coordinating amongst each other rather vs. doing the actual work. If this is the case, consider either breaking the project down in scope into smaller discrete parts or forming a team around people who can perform multiple functions. (Speaking of which, beware of “stakeholders” who have the authority to block or slow down progress but who are not fully committed members of the team and don’t accelerate the flow of work.)

Let’s imagine that your organization is just getting started with cloud. Your IT teams’ first major undertaking is to create a secure and compliant account setup—a “landing zone” for your applications and data—and run it using a cloud operating model. Producing either outcome could require a lot of work and, by extension, a lot of people. In fact, this is precisely where organizations’ first attempt at cloud adoption often fails.

For example, a large financial services customer of ours began their cloud adoption journey by creating three teams: one each for networking, security, and automation. Each team was highly capable and motivated, and while the networking team comprised less than ten people and owned a discrete part of the final solution, the security and automation teams did not. As a direct consequence, the delivery timeline for the security and automation teams took twice as long as originally estimated. At the same time, the ratio of program managers and architects to engineers ballooned to accommodate the additional communication and alignment needs of these overlapping and oversized teams.

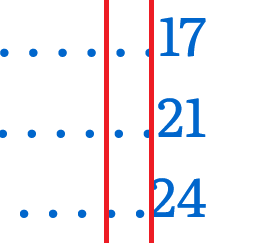

The key to avoiding this bloat is knowing along which lines you can safely split the teams in order to keep them small. Google’s Cloud Adoption Framework can help with this. Among other things, it lists 17 discrete small-scale work packages (called epics) that you can use to form your teams. Crucially, the framework highlights why security cuts across all workstreams, and should never be owned by a single team.

Of project teams and product teams

Team size is not the only consideration. How teams are configured matters just as much. Teams come in many shapes, but we find one distinction particularly instructive: project teams vs. product teams.

Project teams are optimized for efficiency and repeatability, with a well understood definition of “done”. Product teams are essential when there is no “before” or “after” and change is constant.

Google Cloud

Project teams are optimized for efficiency and repeatability, with a well understood definition of “done,” and the ability to move on from one batch of work to the next. They are ideal for large-scale migrations in which dozens or hundreds of applications are moved or modernized and ultimately handed back to their respective owners.

Conversely, project teams are not fit for developing new software solutions. The requirements are defined by what the budget owner thinks the user needs. The engineering team gets one shot to deliver a version 1.0 on time, on scope, on budget, and then they hand their work over to a separate operations team whose primary objective is to meet their own SLAs. The user’s sole avenue for feedback is to file a support ticket, to which the operations team typically has only a binary response: either the solution is demonstrably broken or it’s “working as intended.”

Product teams (see also stream-aligned teams) are essential when there is no “before” or “after,” and change is constant. The architect or the business does not dictate the requirements–rather it’s the user who’s the ultimate authority on informing what needs to be built, with a product owner continuously studying and learning from her users and advocating on their behalf. On a product team, instead of fixed deadlines and milestones, there are only backlogs of user stories that flow into sprints of incrementally feature-rich, usable software. A product team does not abandon its work after version 1.0 and remains dedicated to the solution, continuously expanding its functionality and refining it in perpetuity (or until it is deprecated).

(A cautionary aside: a feature team can have some of the same characteristics as a product team – with the exception that future requirements are still determined by an outside stakeholder—usually the budget holder—rather than actual customer feedback. This risks the product manager acting as a project manager, rather than as a customer advocate.)

Be very deliberate about when you are running a project and when you are building a product! Even the smallest, most talented team with the most manageable scope of work and fullest decision-making autonomy will fail if it is confused about its mission.

Summary

Admittedly, forming and maintaining small, cross-functional teams comes more easily to some organizations than to others. Cloud-native startups and software companies are usually adept at this, since they were built on small teams from day one. But for enterprises whose core business is something other than creating software, the key takeaway is that building your digital transformation team must be a deliberate effort, and should come before you write a single line of code. If you get this part right, everything that follows will be infinitely easier.

If you’re not willing or able to make such a commitment just yet, part one of our digital transformation series will remind you why starting small is the best way to begin any digital transformation journey and where you can start today.

Save the date for Google Cloud Next ’21. Learn from our top developers on how to begin your digital transformation journey. Register here.