In the 15 or so years since I started making WordPress websites, nothing has had more of an impact on my productivity — and my ability to enjoy front-end development — than adding Tailwind CSS to my workflow (and it isn’t close).

When I began working with Tailwind, there was an up-to-date, first-party repository on GitHub describing how to use Tailwind with WordPress. That repository hasn’t been updated since 2019. But that lack of updates isn’t a statement on Tailwind’s utility to WordPress developers. By allowing Tailwind to do what Tailwind does best while letting WordPress still be WordPress, it’s possible to take advantage of the best parts of both platforms and build modern websites in less time.

The minimal setup example in this article aims to provide an update to that original setup repository, revised to work with the latest versions of both Tailwind and WordPress. This approach can be extended to work with all kinds of WordPress themes, from a forked default theme to something totally custom.

Why WordPress developers should care about Tailwind

Table of Contents

Before we talk about setup, it’s worth stepping back and discussing how Tailwind works and what that means in a WordPress context.

Tailwind allows you to style HTML elements using pre-existing utility classes, removing the need for you to write most or all of your site’s CSS yourself. (Think classes like hidden for display: hidden or uppercase for text-transform: uppercase.) If you’ve used frameworks like Bootstrap and Foundation in the past, the biggest difference you’ll find with Tailwind CSS is its blank-slate approach to design combined with the lightness of being CSS-only, with just a CSS reset included by default. These properties allow for highly optimized sites without pushing developers towards an aesthetic built into the framework itself.

Also unlike many other CSS frameworks, it’s infeasible to load a “standard” build of Tailwind CSS from an existing CDN. With all of its utility classes included, the generated CSS file would simply be too large. Tailwind offers a “Play CDN,” but it’s not meant for production, as it significantly reduces Tailwind’s performance benefits. (It does come in handy, though, if you want to do some rapid prototyping or otherwise experiment with Tailwind without actually installing it or setting up a build process.)

This need to use Tailwind’s build process to create a subset of the framework’s utility classes specific to your project makes it important to understand how Tailwind decides which utility classes to include, and how this process affects the use of utility classes in WordPress’s editor.

And, finally, Tailwind’s aggressive Preflight (its version of a CSS reset) means some parts of WordPress are not well-suited to the framework with its default settings.

Let’s begin by looking at where Tailwind works well with WordPress.

Where Tailwind and WordPress work well together

In order for Tailwind to work well without significant customization, it needs to act as the primary CSS for a given page; this eliminates a number of use cases within WordPress.

If you’re building a WordPress plugin and you need to include front-end CSS, for example, Tailwind’s Preflight would be in direct conflict with the active theme. Similarly, if you need to style the WordPress administration area — outside of the editor — the administration area’s own styles may be overridden.

There are ways around both of these issues: You can disable Preflight and add a prefix to all of your utility classes, or you could use PostCSS to add a namespace to all of your selectors. Either way, your configuration and workflow are going to get more complicated.

But if you’re building a theme, Tailwind is an excellent fit right out of the box. I’ve had success creating custom themes using both the classic editor and the block editor, and I’m optimistic that as full-site editing matures, there will be a number of full-site editing features that work well alongside Tailwind.

In her blog post “Gutenberg Full Site Editing does not have to be full,” Tammie Lister describes full-site editing as a set of separate features that can be adopted in part or in full. It’s unlikely full-site editing’s Global Styles functionality will ever work with Tailwind, but many other features probably will.

So: You’re building a theme, Tailwind is installed and configured, and you’re adding utility classes with a smile on your face. But will those utility classes work in the WordPress editor?

With planning, yes! Utility classes will be available to use in the editor so long as you decide which ones you’d like to use in advance. You’re unable to open up the editor and use any and all Tailwind utility classes; baked into Tailwind’s emphasis on performance is the limitation of only including the utility classes your theme uses, so you need to let Tailwind know in advance which ones are required in the editor despite them being absent elsewhere in your code.

There are a number of ways to do this: You can create a safelist within your Tailwind configuration file; you can include comments containing lists of classes alongside the code for custom blocks you’ll want to style in the block editor; you could even just create a file listing all of your editor-specific classes and tell Tailwind to include it as one of the source files it monitors for class names.

The need to commit to editor classes in advance has never held me back in my work, but this remains the aspect of the relationship between Tailwind and WordPress I get asked about the most.

A minimal WordPress theme with a minimal Tailwind CSS integration

Let’s start with the most basic WordPress theme possible. There are only two required files:

style.cssindex.php

We’ll generate style.css using Tailwind. For index.php, let’s start with something simple:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en"> <head> <?php wp_head(); ?> <link rel="stylesheet" href="<?php echo get_stylesheet_uri(); ?>" type="text/css" media="all" /> </head> <body> <?php if ( have_posts() ) { while ( have_posts() ) { the_post(); the_title( '<h1 class="entry-title">', '</h1>' ); ?> <div class="entry-content"> <?php the_content(); ?> </div> <?php } } ?> </body>

</html>There are a lot of things a WordPress theme should do that the above code doesn’t — things like pagination, post thumbnails, enqueuing stylesheets instead of using link elements, and so on — but this will be enough to display a post and test that Tailwind is working as it should.

On the Tailwind side, we need three files:

package.jsontailwind.config.js- An input file for Tailwind

Before we go any further, you’re going to need npm. If you’re uncomfortable working with it, we have a beginner’s guide to npm that is a good place to start!

Since there is no package.json file yet, we’ll create an empty JSON file in the same folder with index.php by running this command in our terminal of choice:

echo {} > ./package.jsonWith this file in place, we can install Tailwind:

npm install tailwindcss --save-devAnd generate our Tailwind configuration file:

npx tailwindcss initIn our tailwind.config.js file, all we need to do is tell Tailwind to search for utility classes in our PHP files:

module.exports = { content: ["./**/*.php"], theme: { extend: {}, }, plugins: [],

}If our theme used Composer, we’d want to ignore the vendor directory by adding something like "!**/vendor/**" to the content array. But if all of your PHP files are part of your theme, the above will work!

We can name our input file anything we want. Let’s create a file called tailwind.css and add this to it:

/*!

Theme Name: WordPress + Tailwind

*/ @tailwind base;

@tailwind components;

@tailwind utilities;The top comment is required by WordPress to recognize the theme; the three @tailwind directives add each of Tailwind’s layers.

And that’s it! We can now run the following command:

npx tailwindcss -i ./tailwind.css -o ./style.css --watchThis tells the Tailwind CLI to generate our style.css file using tailwind.css as the input file. The --watch flag will continuously rebuild the style.css file as utility classes are added or removed from any PHP file in our project repository.

That’s as simple as a Tailwind-powered WordPress theme could conceivably be, but it’s unlikely to be something you’d ever want to deploy to production. So, let’s talk about some pathways to a production-ready theme.

Adding TailwindCSS to an existing theme

There are two reasons why you might want to add Tailwind CSS to an existing theme that already has its own vanilla CSS:

- To experiment with adding Tailwind components to an already styled theme

- To transition a theme from vanilla CSS to Tailwind

We’ll demonstrate this by installing Tailwind inside Twenty Twenty-One, the WordPress default theme. (Why not Twenty Twenty-Two? The most recent WordPress default theme is meant to showcase full-site editing and isn’t a good fit for a Tailwind integration.)

To start, you should download and install the theme in your development environment if it isn’t installed there. We only need to follow a handful of steps after that:

- Navigate to the theme folder in your terminal.

- Because Twenty Twenty-One already has its own

package.jsonfile, install Tailwind without creating a new one:

npm install tailwindcss --save-dev- Add your

tailwind.config.jsonfile:

npx tailwindcss init- Update your

tailwind.config.jsonfile to look the same as the one in the previous section. - Copy Twenty Twenty-One’s existing

style.cssfile totailwind.css.

Now we need to add our three @tailwind directives to the tailwind.css file. I suggest structuring your tailwind.css file as follows:

/* The WordPress theme file header goes here. */ @tailwind base; /* All of the existing CSS goes here. */ @tailwind components;

@tailwind utilities;Putting the base layer immediately after the theme header ensures that WordPress continues to detect your theme while also ensuring the Tailwind CSS reset comes as early in the file as possible.

All of the existing CSS follows the base layer, ensuring that these styles take precedence over the reset.

And finally, the components and utilities layers follow so they can take precedence over any CSS declarations with the same specificity.

And now, as with our minimal theme, we’ll run the following command:

npx tailwindcss -i ./tailwind.css -o ./style.css --watchWith your new style.css file now being generated each time you change a PHP file, you should check your revised theme for minor rendering differences from the original. These are caused by Tailwind’s CSS reset, which resets things a bit further than some themes might expect. In the case of Twenty Twenty-One, the only fix I made was to add text-decoration-line: underline to the a element.

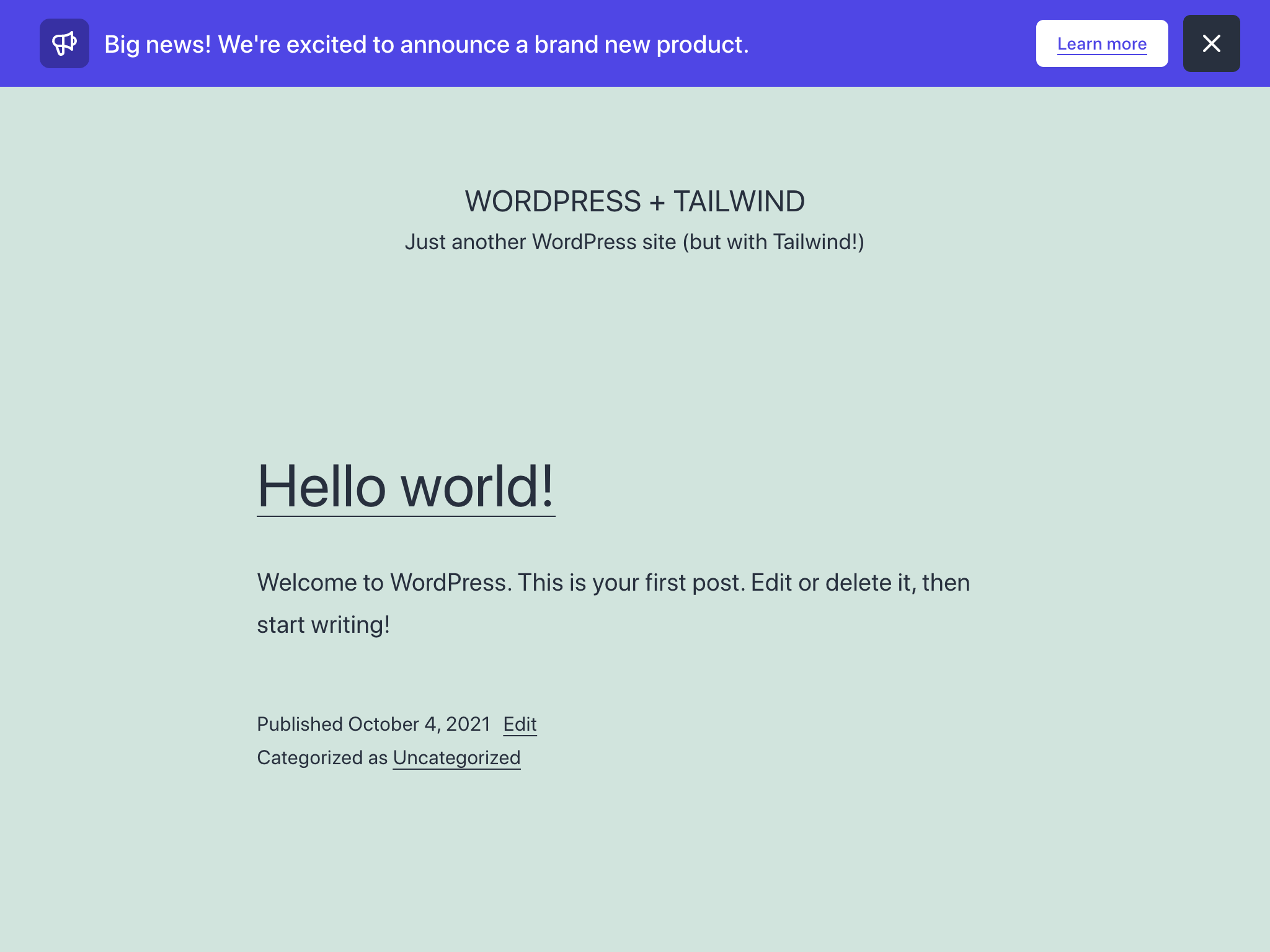

With that rendering issue resolved, let’s add the Header Banner Component from Tailwind UI, Tailwind’s first-party component library. Copy the code from the Tailwind UI site and paste it immediately following the “Skip to content” link in header.php:

Pretty good! Because we’re now going to want to use utility classes to override some of the existing higher-specificity classes built into the theme, we’re going to add a single line to the tailwind.config.js file:

module.exports = { important: true, content: ["./**/*.php"], theme: { extend: {}, }, plugins: [],

}This marks all Tailwind CSS utilities as !important so they can override existing classes with a higher specificity. (I’ve never set important to true in production, but I almost certainly would if I were in the process of converting a site from vanilla CSS to Tailwind.)

With a quick no-underline class added to the “Learn more” link and bg-transparent and border-0 added to the dismiss button, we’re all set:

It looks a bit jarring to see Tailwind UI’s components merged into a WordPress default theme, but it’s a great demonstration of Tailwind components and their inherent portability.

Starting from scratch

If you’re creating a new theme with Tailwind, your process will look a lot like the minimal example above. Instead of running the Tailwind CLI directly from the command line, you’ll probably want to create separate npm scripts for development and production builds, and to watch for changes. You may also want to create a separate build specifically for the WordPress editor.

If you’re looking for a starting point beyond the minimal example above — but not so far beyond that it comes with opinionated styles of its own — I’ve created a Tailwind-optimized WordPress theme generator inspired by Underscores (_s), once the canonical WordPress starter theme. Called _tw, this is the quick-start I wish I had when I first combined Tailwind with WordPress. It remains the first step in all of my client projects.

If you’re willing to go further from the structure of a typical WordPress theme and add Laravel Blade templates to your toolkit, Sage is a great choice, and they have a setup guide specific to Tailwind to get you started.

However you choose to begin, I encourage you to take some time to acclimate yourself to Tailwind CSS and to styling HTML documents using utility classes: It may feel unusual at first, but you’ll soon find yourself taking on more client work than before because you’re building sites faster than you used to — and hopefully, like me, having more fun doing it.