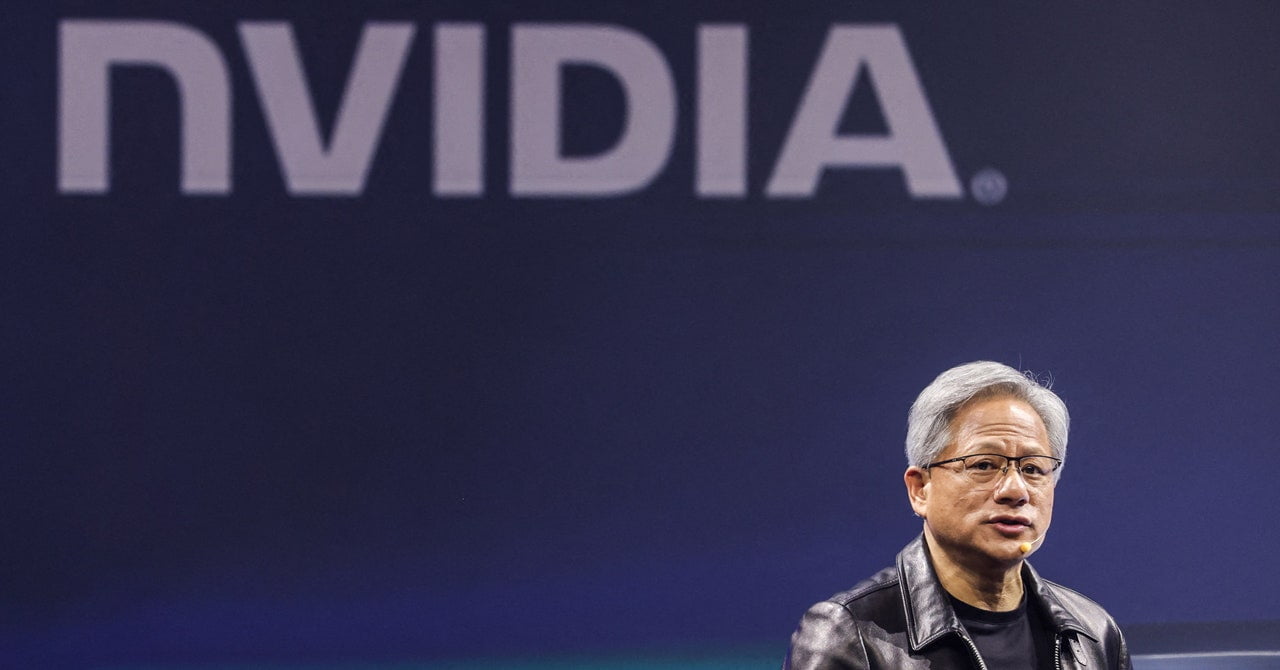

Unless you were really into desktop PC gaming a decade ago, you probably didn’t give Nvidia much thought until recently. The company makes graphics cards, among other tech, and has earned great success thanks to the strength of the gaming industry. But that’s been nothing compared to the explosive growth Nvidia has enjoyed over the past year. That’s because Nvidia’s tech is well-suited to power the machines that run large language models, the basis for the generative AI systems that have swept across the tech industry. Now Nvidia is an absolute behemoth, with a skyrocketing stock value and a tight grip on the most impactful—and controversial—tech of this era.

This week on Gadget Lab, we welcome WIRED’s Will Knight, who writes about AI, as our guest. Together, we boot up our Nvidia® GeForce RTX™ 4080 SUPER graphics cards to render an ultra high-def conversation about the company powering the AI boom.

Read Lauren’s interview with Nvidia cofounder and CEO, Jensen Huang. Read Will’s story about the need for more chips in AI computing circles, and his story about the US government’s export restrictions on chip technology. Read all of our Nvidia coverage.

Will recommends WhisperKit from Argmax for machine transcription. Mike recommends getting your garden going now; it’s almost spring. Lauren recommends Say Nothing, a book by Patrick Radden Keefe.

Will Knight can be found on social media @willknight Lauren Goode is @LaurenGoode. Michael Calore is @snackfight. Bling the main hotline at @GadgetLab. The show is produced by Boone Ashworth (@booneashworth). Our theme music is by Solar Keys.

You can always listen to this week’s podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here’s how:

If you’re on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts, and search for Gadget Lab. If you use Android, you can find us in the Google Podcasts app just by tapping here. We’re on Spotify too. And in case you really need it, here’s the RSS feed.

Note: This is an automated transcript, which may contain errors.

Lauren Goode: Mike.

Michael Calore: Lauren.

Lauren Goode: Let’s go back about 10 years. When you thought of Nvidia back then, what did you think of?

Michael Calore: I think of big CES press conferences with the company talking about things like Tegra supercomputing chips and these big events that generally just served word soup.

Lauren Goode: That is very accurate. Can you guess what the stock price of Nvidia was then?

Michael Calore: I have no idea.

Lauren Goode: Are you ready for it?

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: It was between $3 and $5.

Michael Calore: What is it now?

Lauren Goode: It’s hovering around $800.

Michael Calore: Oh, my God. Stop.

Lauren Goode: Mm-hmm. Seriously.

Michael Calore: Well, we don’t own tech stocks here, so sad for us. But what happened to Nvidia?

Lauren Goode: Basically, Nvidia started to take over the computing world.

Michael Calore: OK, we need to talk about why.

Lauren Goode: We really do. Let’s do it.

[Gadget Lab intro theme music plays]

Lauren Goode: Hi, everyone. Welcome to Gadget Lab. I’m Lauren Goode. I’m a senior writer at WIRED.

Michael Calore: And I’m Michael Calore. I am WIRED’s director of Consumer Tech and Culture.

Lauren Goode: We’re joined this week by WIRED senior writer, Will Knight, who joins us from Cambridge, Massachusetts. He’s on Zoom and he has averted his eyes from the latest AI research paper to humor us on the Gadget Lab. Hi, Will.

Will Knight: Hello.

Lauren Goode: Thanks for being here.

Will Knight: Thanks for having me.

Lauren Goode: OK. We brought Will on, because today we are talking about the wild rise of Nvidia, the company that started in the 1990s selling graphics chips for video games on PCs. That is oversimplifying it a little, but basically from the earliest days, Nvidia made a bet on accelerated computing versus general purpose computing. They made custom chips that turbocharge the functions of the personal computer. But as Mike and I were talking about, the Nvidia of today is not your Gen X graphic chips maker. Its co-founder and chief executive, Jensen Huang, has consistently positioned the company right ahead of the curve. Right now, Nvidia holds the majority of the market share of AI computing chips. It’s also worth nearly $2 trillion.

I had a chance to sit down with Jensen in recent months for a WIRED story. I’m sorry to disappoint all of you, but you’re not going to hear those interviews here. You’re going to have to read it in WIRED. I might also recommend checking out the Acquired Podcast for a very, very long multi-part series on Nvidia that does end with a conversation with Jensen. But we wanted to give you the most clear cut story here of how Nvidia ended up where it did and what the future holds for it.

We should probably start with how Nvidia started and maybe not spend too long on it, but talk about that era of the personal computer, the emergence of it in the ’90s and how we transitioned to this, right?

Michael Calore: Yes. The company started in 1993, you said?

Lauren Goode: That’s correct. It’s just about as old as WIRED.

Michael Calore: What was their big breakthrough that put them on the map?

Lauren Goode: Well, we should go back to what PCs were like in the 1990s and specifically what games on PCs were like. Games were starting to become more popular, but they were powered by CPUs, central processing units, and then graphics were kind of like an also-ran. These chips could also do graphics, but they weren’t very good. And then Nvidia had this idea to move more towards a customized or specialized unit, a graphics processing unit, which is how we get GPU. A lot of our listeners are going to know what this means, CPU and GPU and the differences, but other people just probably hear these acronyms all the time and don’t fully understand what they mean and how they power a computer.

Jensen Huang was working at a company called LSI Logic at the time that Nvidia was first conceived. Two of his friends, his co-founders, said to him, “Hey, let’s start this dedicated graphics card company.” They convinced him, they convinced Jensen. He resigned from his other job and they all started Nvidia. Legend has it that they hatched this whole idea in a Denny’s diner. That’s 1993, Nvidia begins.

Michael Calore: When we were all hanging out in Denny’s diners.

Lauren Goode: I think some people still do. Good for them.

Michael Calore: How did it go? Did it go smoothly? Were there bumps?

Lauren Goode: There were definitely some bumps in the road in the mid to late-1990s. One of the first chips that they put out was pretty much a failure and the company nearly went bankrupt. They had to lay off a lot of people, something like close to 70 percent of the staff, and then they had to come up with a plan for a new chip super, super quickly. But a lot of tech production cycles, they’re 18 to 24 months, and that was certainly the case for chips. Nvidia didn’t have that much runway. They also didn’t have their own fab, which is a place where you make all the chips. You’re relying on partners to do this. You’re working with them hand in hand on the designs and then they’re sending chips to you and you’re making tweaks and sending it back and stuff. It’s a long process.

Nvidia did something smart, which is they started using emulators. They started crafting this second ship that they had to launch very quickly in software and testing it that way. They were able to spin up something new within… I think it was six-ish months called the RIVA 128. That basically saved the company in its earliest days. There have been a few moments like that in Nvidia’s history where they’ve made a bet on this next thing that’s going to happen and you’re betting the farm and so far they’ve just managed to grow the farm. It’s like big ag now. It’s massive.

Michael Calore: I want to ask Will a question about what a lot of people consider to be the birth of this modern era of AI, which Nvidia is a big part of. Can you tell us about what happened roughly 10, 12 years ago in the world of artificial intelligence computing?

Will Knight: Yeah, sure. Nvidia’s very much wound up in the origins of modern AI and we forget now because everything’s machine learning based and AI algorithms so capable. But back before 2010, 2012, people were coding all these things by hand to try and have machines do more intelligent tasks. There was a group of people who focused on this neural network approach, which is totally out of vogue. It hadn’t worked. It had been too puny to do anything very impressive and they kept going on it. Around 2010, there was this conference of enough data from the internet, these bigger neural network algorithms, which was possible to run on GPUs because they were very paralleled and the computations you want to do are inherently parallel.

Those deep learning researchers figured out that they could supercharge their algorithms on GPUs. In 2012, there was this competition to try and see who could write an algorithm that could classify things in images best. The deep learning people suddenly blew everybody else out of the water and they were using GPUs to make that happen. It wasn’t as if Nvidia really foresaw that, it was just that their chips happened to be perfect for that task, and then I think Jensen ran with it.

Lauren Goode: And then there was another moment in 2017, Will, when Google put out its Transformer paper. That also was a pretty big catalyst for this new era of AI and Nvidia was a part of that, too.

Will Knight: Right. Yeah. That Transformer paper was this new way to do machine learning on language especially and it was incredibly powerful. It turns out it’s what’s given us all these language models with their remarkable capabilities. In the run-up to that, it was a lot of image recognition, voice recognition, and Nvidia deserves a lot of credit for building these tools that loads of people were jumping on. When the Transformer stuff happened, it was the beginning of this generative AI language model chatbot era, where things really gathered a lot of steam and took off massively as we’ve seen.

Michael Calore: Yes. Now, the industry is just exploding and you’ve got startups and large companies competing for computing power, right? Nvidia GPUs famously became very, very difficult to find for a few years. They were also used in bitcoin mining and cryptocurrency mining, so they were worth more than their weight in gold for a while. The company’s still trying to recover from this supply chain issue. They’re still trying to flood the world with chips, but the thing that it seems like, Lauren, from the talk that you had with Jensen that he’s most focused on as far as hardware goes in the future, is doing this type of computing at scale, like doing data centers just for AI and very large appliances that companies buy to do their own AI computations on site.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. The data center business is already a pretty big business for Nvidia, but when he and I first sat down in early January to talk about this, it was one of the first things he brought up. He had just gotten out of a meeting with a technology partner to talk about these AI data centers again. I think that the simplest way to describe this is that the whole computing industry has really moved from on-device computing to cloud computing. On-device is those old days of graphics cards jammed into your personal computer and most, if not all, of the accelerated computing is happening there. And then, with giant tech companies spinning up their cloud computing options like Google and Amazon, a lot of that computation has shifted to the cloud. Microsoft is a part of this, too. Your inputs go from your computer to a server somewhere and then the output comes back to your device. This is part of what enables software to, quote, unquote, “scale” so quickly. People in tech love using that word, VCs love it. Everyone loves scale.

Michael Calore: Scale, that’s where the money is.

Lauren Goode: That’s right. We must scale up. We might have to scale up WIRED these days. Nvidia is a part of that and now it plans to develop more of these AI supercomputing data centers that help power not just software companies but also manufacturers or self-driving cars or biotech companies that are starting to use more and more AI

Michael Calore: Nice.

Will Knight: That AI factory answer I thought was really fascinating in your interview. I think it probably also reflects the fact that, as we’ve seen AI take off, a lot of the really key players in it that are doing the algorithms like Google, Meta, Microsoft have studied to build their own chips. One of the things that they can do that could potentially give them an advantage over or an edge over Nvidia is build… They already build these data centers, networking the chips altogether, and he also talked about that networking company. But I think the idea of building their own huge data center is very much optimizing the networking and all these capabilities.

It reflects partly the fact that you have models that are so large that you need to network tens of thousands of chips as efficiently as you possibly can when it was inconceivable a decade ago. But I think it does show that he’s very smart about preempting what could be a bit of a threat as well as the opportunity to deliver that AI to lots of different customers. The likes of Google are going to be trying to deliver that to those manufacturers and car makers and so on. I thought that AI factory thing was very interesting.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. Will brings up a good point. The Mellanox acquisition for Nvidia was a pretty savvy one because it provided that networking technology at the chip level, but some of the companies that Will mentioned also have incredibly deep pockets and probably have the technical capabilities to do something similar, build something similar, and they’re certainly trying. We should take a quick break and when we come back we’ll talk about Nvidia’s competition.

[Break]

Lauren Goode: Nvidia is at the top of the AI pile right now. Its supercomputing GPUs are in very high demand. It has built a solid moat around itself with this programming model, Cuda. It has those data centers we just talked about and it’s making strategic investments in other smaller AI companies, but what’s stopping another big tech company from doing this? In fact, others are… Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, they all have a lot of cash and grand plans to accelerate their AI computing efforts. Will, who do you think is the most formidable competitor to Nvidia? Maybe it’s a company I haven’t even named here.

Will Knight: Well, I think the most obvious formidable competitor is Google because it’s been developing its own AI chips for a while and it’s obviously also a huge player in AI software. It’s interesting what they’re doing, because Nvidia might have the most powerful, most capable chips, but if you can network together several less powerful chips as if there’s no… or if there’s very minimal bottleneck between them, you can do things more impressively. Google’s been focusing actually a lot of attention on that. It did a recent experiment where it showed it’s possible to network 50,000 GPUs together to do language model training and usually you do 10,000. That bottleneck is really important.

It basically increases the size of the overall supercomputer even if your chips are not quite as cutting edge or powerful. They’ve been doing a bunch of interesting stuff with their own optical networking between chips to try and speed that up. I think they’re probably the one that’s most in mind, but other companies like Microsoft is trying to develop its own AI chips. There are also a bunch of startups like Cerebras and even ones doing things in non-conventional. I think that could blindside, I guess, Nvidia at some point, but I think Google’s the big one that Jensen’s probably looking over his shoulder at.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. I thought it was interesting that when Google announced its Gemini AI models, they left Nvidia of the announcement because they’re now relying on it’s TPU, its tensor processing units.

Michael Calore: Really? I’m going to bet on AWS as the dark horse here, Amazon Web Services. Obviously, they’ve been working on this for a long time and they don’t have as much to show for it, but I think that’s holding their cards to lay them down at the right time.

Lauren Goode: Interesting.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Will Knight: There was a very interesting announcement where Anthropic, one of these competitors to OpenAI, which was founded by people from that company, got a huge investment from Amazon AWS. Part of that deal was that they were going to run their next model, their next competitor to GPT-4 or 5 on Amazon silicon. That will show that their silicon is competitive and that’s going to be one of the ways they try and sell that to all their customers.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: Will, where do AMD and Intel fit into all of this?

Will Knight: Yeah. I think AMD’s come out recently with some chips that are more competitive and likely to be bit more of an option for people developing models. Intel… I mean, it is trying to get back into the game of making these but it’s it very behind. But it’s got a huge amount of money from the US government to try and improve what it’s doing, so that could include making chips for Nvidia. They want to do that. They want to try and have this cutting edge process, but they’re also looking to develop their own chips somewhere down the line. I think they’re a long way off.

Lauren Goode: They’ve been on a bit of a press blitz recently. You wrote about them in WIRED.com last week.

Will Knight: Yeah. Well, they are receiving a huge… I mean, it’s reported, but I think it’s fair to say they’re going to receive a huge injection of cash from the CHIPS Act. The US government is trying to make sure that America is competitive when it comes to making chips, because they’re worried about the supply chain, what could happen if access to TSMC or Samsung was cut off. They’re determined for them to make a comeback. Intel has started to produce chips that are much more close to TSMC. They’ve been following this really aggressive path and they announced that Microsoft is going to be making its AI chips on its platform. It remains to be seen how great a comeback they can make.

Michael Calore: I’m curious about the other side of that. With the US government trying to support homegrown chip fabs and get more of this technology built in the United States, it also has put export controls on that technology so that we can’t share our latest technological advancements with other countries, particularly with China. Can one of you explain how this is helping shape the industry?

Lauren Goode: Well, I can answer for Nvidia and then maybe Will can go into a little bit more depth about the broader industry. But Nvidia has been affected by the export controls. These were first announced in August of 2022. There have since been some updates to the export controls, but basically Nvidia had to start making or tweaking its chips so that they were control compliant and they could still ship to China because China is, obviously, a very important market for Nvidia as it is for a lot of tech companies. But the goal here is that the US and other western countries have the, quote, unquote, “best technology” access to the most advanced technology and that we’re not just giving that technology away to China. Nvidia wanted to continue to sell in that market, but they had to change. It’s tweaking the formula to make sure that they weren’t selling the best stuff there. It’s also affecting their data center business as well. Will, Do you have a sense of how that’s affecting the broader chip industry?

Will Knight: I think, it’s one of the more fascinating moves in tech policy that the US government has made certainly in recent years, because they’re basically cutting off one of the most lucrative and important industry’s access to the biggest market and the fastest growing market to try and maintain this technological edge. People within the chip industry are quite worried, I think, rightly that China is going to simply encourage Chinese companies to be more competitive and to gain more of an edge. The whole rational is that it’s so difficult to do chip making and all of the components and technologies and hardware you need come from American allies or America, so you can limit that. But there have been some recent moves to suggest that China may be moving more quickly in developing more cutting edge chips.

Lauren Goode: Let me ask both of you guys a question. AI is so obviously imperfect, especially in the whole era of generative AI. Mistakes, hallucinations, biases, and that can be as inconsequential as it performs simple math wrong, like when we all know the answer to two plus two is four. Or it can be as consequential as a self-driving car not recognizing a human being that has fallen down in the road or it could be part of an erroneous drone strike. This is really, really serious stuff and I am wondering if the companies that are not just hardware makers but also platform companies and software makers… What happens around public sentiment of AI and those companies in particular when things go wrong? Nvidia has the ability to say right now, “We’re just the hardware maker. Yes, we have a platform that Cuda platform that all the developers are locked into, but we just make the hardware.” If you’re Google or Microsoft or Amazon and you really own that full stack of AI computing, what happens when things go wrong?

Will Knight: Well, one of the things that you’re alluding to is things can go wrong with machine learning systems in completely different ways, I think. A big question out there, say, in self-driving cars is how you determine where the error or the problem occurred. That can be quite difficult when you’re using machine learning, which is inherently probabilistic, as well as code that follows certain rules or hardware that follows certain rules. If you could follow it back to a buggy element of a chip, I guess you could point the finger at them. But I think that that’s one of the things that actually they’re trying to work out in a lot of industries that are increasingly depending on AI is how you even determine where errors come from, how you figure out how reliable something is, which isn’t a normal engineering, because dealing with these systems which don’t actually behave the same way when you run them twice… So, you have to kind of engineer around that.

Michael Calore: I have been tickled, amused by the fact that the revolution that we’re seeing on the ground is a chatbot revolution. Everybody is very, very excited about chatbots, but I do think it’s useful at looking how this is going to be adopted into society, because chatbots are very visceral. People have conversations with their phones, people have conversations with a customer service agent that may or may not be a human. People can interact with an AI version of their favorite celebrity in virtual reality. It’s novel, it’s kind of useful, and when it does the thing that you want it to do, then it feels like the future. It feels like magic. It feels like you just experienced what the future is going to look like. I think the big leap is going to be when we learn that some of the systems that oppress us, things like banking, admissions to colleges…

Lauren Goode: Housing, job applications, healthcare, yep.

Michael Calore: Law enforcement. When those systems become more and more reliant on machine intelligence and we notice that the oppression is staying the same or getting worse and it is not really helping us, that our perception of these things are the future, cool, will change to, “These things are the future. This sounds terrible.” I don’t really know what to say about hallucinations, because I think you really have to be embedded in the tools and really using the tools in order to see those smaller, more nuanced problems, and to gain an understanding of them in most people. By most people, I mean like 95 percent of the people out there are not deep in those tools and they’re not super familiar with them, but they are encountering them whether they know it or not. I think the next couple of years are going to be wild.

Lauren Goode: There’s just so much potential for additional layers of obfuscation.

Michael Calore: Yes.

Lauren Goode: Not being able to actually pinpoint where the liability should.

Michael Calore: Yes. Yes. Really, I think it’s going to… People are going to get even more upset at tech companies and billionaires and all the things that they’re upset about now.

Lauren Goode: Does that upset you, Mike? I know you love billionaires.

Michael Calore: I love them as people, yes. They’re great people. I’m sure some of them.

Will Knight: I’ve been thinking about this in the context of self-driving cars, because on the one hand I think it’s really shocking that—In some ways, it’s really insane that they test these experimental vehicles on the roads with pedestrians who haven’t signed up for it at all. But then on the other hand, 35,000 people die a year because of terrible human drivers. We haven’t had any kind of public discourse about that. It’s just being done by the companies that have the most money, but, I mean, it is a really interesting thing to think about how to weigh those things.

Lauren Goode: It’s interesting to think about the blind spots. I mean, one of the hardware companies that’s powering self-driving cars, someone running one of the labs told me that they realized after they started deploying the cars, they hadn’t tested for Halloween. Truly, they hadn’t tested for when people are crossing the street on a dark night wearing all different kinds of costumes that might obfuscate them as human beings. They had to go back and test that.

Michael Calore: Is it a pantomime horse with two humans or is it an actual horse with no humans?

Lauren Goode: Right. Is that really Batman?

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: All right. Well, we’re not going to be able to answer all of these questions on this week’s podcast, but hopefully we gave you a good primer on Nvidia and where it’s going. Will, we very much appreciate you being a part of that. We’re going to take another quick break and then come back with all of our recommendations.

[Break]

Lauren Goode: All right, Will. What is your recommendation?

Will Knight: My recommendation is this application called WhisperKit, which is from a company called Argmax, which was founded by some Apple developers who left to do their own thing. I think it’s appropriate because it’s a good example of the importance of the edge. This isn’t like sending yourself to the cloud. You can do quite advanced voice transcription, which is obviously important for journalists and other people on your computer using… They use some software that came from OpenAI, but they just optimized it very much for your own hardware. It’s a good example of how… Maybe a lot of AI is also going to happen on the edge, as well as in the cloud.

Lauren Goode: And what are you using it for?

Will Knight: Recording everybody.

[Lauren and Michael laugh]

Michael Calore: Your own home speech recognition applications that you’re running?

Will Knight: Yeah, just all the time. I can just remember everything. I can just settle arguments by winding back the tape and playing what people said.

Lauren Goode: How many arguments do you get into? Will, you don’t strike me as argumentative.

Will Knight: You’d be surprised, but, no, I don’t really use that. I was using one of these cloud platforms for transcription, but I wanted something that wasn’t… I kept running into the limit of how much I could record, which actually is very annoying and they’re quite expensive. I figured it’d be interesting to play with this for transcribing interviews.

Michael Calore: And pretty accurate?

Will Knight: Yeah, it’s pretty accurate. I use this thing called Whisper from OpenAI, which is pretty good. Yeah, you have to go back, make sure you’re not misquoting people, but, yeah, pretty good.

Lauren Goode: How secure is it? Would you use it to process your most sensitive interviews?

Will Knight: Well, it’s all running on my computer. Assuming my computer hasn’t been hacked, which is never a given, it certainly seems more secure than sending it to the cloud.

Lauren Goode: Interesting. Yeah. I use Google’s transcription service, which is pretty darn good. It does it on device, but then I do send it to the cloud. Use Otter, right?

Michael Calore: I use Mechanical Turk. No, I’m kidding. I use Alice.

Lauren Goode: What’s that?

Michael Calore: Alice AI. It’s another one of the front ends for… I think they use Google’s transcription service. But also, I have a Pixel phone, so if I record on my Pixel phone then it just freely translates it.

Lauren Goode: Right. My second phone’s a pixel for all my shady activity.

Michael Calore: Yep.

Lauren Goode: Thank you for that, Will. We’re going to link that in the show notes. Mike, what’s your recommendation?

Michael Calore: Get your garden ready. This is my recommendation. This week, February turns into March and in just a couple more weeks it will be spring. Spring will have sprung and it is time to plant the vegetables and the fruits and the flowers that you would like to be eating this summer. If you live in a slightly warmer part of the country like we do here in California, or if you live in the south, then you can start planting outdoors pretty much now or next week. If you live in a colder part, you will have to use a greenhouse or you can do like I did and get a seedling mat, which is like a heated mat that you put your seedlings on. You can leave them on your enclosed porch or in your basement or your attic and make sure that you can grow healthy plants.

I, like many people, got into gardening a little bit more than usual during the pandemic because all of a sudden I had all this time at home that I could pay attention to the plants. Now that I’m in the office most of the days, my garden has gone into disarray. There’s a lot of weeds. I’ve switched to succulents for most of it, but I am determined to do some California wildflowers this year and to do some peppers that we can all enjoy either fresh or pickled this summer. I would say that if you are a person who has always thought about gardening or if you used to be a serious gardener, this is a big reminder. It’s a big flashing light sign that now is the time to plant again.

Lauren Goode: This is a great recommendation.

Michael Calore: Thank you. Are you going to plant anything?

Lauren Goode: I have already started with the plants. I recently picked up some dichondra silver, some lotus. I have Angel vine going pretty strong right now under our skylights in the kitchen.

Michael Calore: Can you eat any of these things?

Lauren Goode: No, but I have one plant… You know this plant, Kevin. It was rescued from a demolition site during the pandemic. My neighbor gave me this scrawny little thing in a pot and it’s a lemon tree. And I grew it. I mean, it’s really healthy now. It’s attached to a lattice and, yeah, I water it, I give it plant food. It provided a lot of lemons last year and I’m already seeing… The green ones are there now. What is that called when it’s not ripe? Unripe. Yeah. Kevin the Lemon Tree is doing… Actually, our friend Cyra and Adrian named it when they were drunk one night like, “OK, it’s Kevin.” Kevin’s doing great. Everyone come over for lemons.

Michael Calore: Nice.

Lauren Goode: But, yeah, no, I love it. It’s great. There are some other plant. There’s a Japanese maple in front of my place, but I don’t have to water that or anything. The Japanese maple houses the little nest from the hummingbirds last year.

Michael Calore: OK. Lauren, I just have to point out that all these things that you’re mentioning are plants and trees.

Lauren Goode: I know. I know. But you’re talking about planting. They are plants. You plant plants.

Michael Calore: This year, try herbs, charred, leafy greens, peppers. Get them going.

Lauren Goode: OK. My brother actually got me an herb garden from Christmas and I sent it back.

Michael Calore: Is it like one of the Click & Grow ones?

Lauren Goode: Yeah, it was like one of those indoor ones and I didn’t want it inside, but maybe I’ll do it outside.

Michael Calore: Does your brother listen to the show and will now be offended?

Lauren Goode: He does. Hi, Gerald. Yeah, he does. He listened to the… Yes, he listened to the episode where we’re talking about the Bono book.

Michael Calore: Oh, yes, yes.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. Yeah

Michael Calore: OK. Another gift that you returned?

Lauren Goode: Yeah.

Michael Calore: Before we go too far into plantasia, what is your recommendation?

Lauren Goode: Plantasia?

Michael Calore: What is your recommendation?

Lauren Goode: My recommendation is a book that is soon spawning a television show. Although I did just look it up, I thought the TV show was coming out soon and there’s no release date for it yet. It’s later in 2024. The book is called Say Nothing. It’s by our colleague at The New Yorker, Patrick Radden Keefe. Mike is smiling right now because we were saying earlier how saying the phrase my colleague can be so self-aggrandizing because I don’t actually know Patrick Radden Keefe. I admire his writing, a great deal.

Michael Calore: He used to write for WIRED.

Lauren Goode: I read more than one of his books. You told me that this morning and I was very excited. He worked… What is it called, Danger Zone?

Michael Calore: Danger Room. It was our defense tech section.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. How long ago was this?

Michael Calore: I don’t know. 2008, 2009 probably.

Lauren Goode: I mean, he’s in our Slack and we’re talking about him right now, but I’ve never met him. I think his writing is brilliant. I’ve read at least a couple of his books. Say Nothing is about the troubles in Ireland and it’s multiple stories interwoven. It’s one of the best books I’ve read in 2023 by far. I read it towards the end of the year, so it’s still fresh in the brain. It came out sooner, though, I think 2019, and now has been turned into a television show. It has been snapped up by FX. Here in the United States, it’s going to be airing on Hulu at some point this year. We don’t know when though, so keep an eye out for that. In the meantime, read the book.

Michael Calore: Nice.

Lauren Goode: That’s great.

Michael Calore: Nice.

Lauren Goode: Our colleague, by our colleague. All right. That’s our show this week. Will, thank you so much for joining us.

Will Knight: Thanks for having me.

Lauren Goode: And thanks to all of you for listening. If you have feedback, you can find all of us on the site formerly known as Twitter. Worst name change ever.

Michael Calore: Bluesky.

Lauren Goode: Bluesky, that’s right. Just check the show notes. Our producer is the excellent Boone Ashworth and we’ll be back next week.

[Gadget Lab outro theme music plays]

In recent years, Nvidia has emerged as a dominant force in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). The company’s GPUs (graphics processing units) have become the go-to choice for AI researchers and developers, powering some of the most advanced AI systems and applications. This rise to dominance can be attributed to several key factors, including Nvidia’s focus on GPU technology, strategic partnerships, and investments in research and development.

One of the main reasons behind Nvidia’s success in AI is its GPU technology. GPUs are highly parallel processors that excel at handling large amounts of data simultaneously. This makes them ideal for AI applications, which often involve complex computations and massive datasets. Nvidia recognized this potential early on and invested heavily in developing GPUs specifically designed for AI workloads.

The company’s flagship GPU architecture, known as NVIDIA Ampere, has been widely adopted by AI researchers and developers. Ampere GPUs offer exceptional performance and efficiency, enabling faster training and inference times for AI models. This has allowed Nvidia to establish itself as a leader in the AI hardware market, with its GPUs being used in a wide range of industries, including healthcare, finance, and autonomous vehicles.

In addition to its focus on GPU technology, Nvidia has also forged strategic partnerships with major players in the AI industry. One notable partnership is with leading cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. These partnerships have enabled Nvidia to make its GPU technology readily available to developers through cloud-based services, making it easier for organizations to adopt AI solutions without the need for significant hardware investments.

Furthermore, Nvidia has collaborated with software companies to optimize popular AI frameworks and libraries for its GPUs. This includes partnerships with companies like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and Caffe. By working closely with these software developers, Nvidia ensures that its GPUs deliver optimal performance for AI workloads, further solidifying its position as a dominant force in the AI ecosystem.

Nvidia’s commitment to research and development has also played a crucial role in its rise as an AI powerhouse. The company invests a significant portion of its revenue into R&D, allowing it to continuously innovate and push the boundaries of AI technology. Nvidia’s research efforts have resulted in breakthroughs such as the development of specialized AI accelerators like the Tensor Core, which further enhances the performance of its GPUs for AI workloads.

Moreover, Nvidia has been actively involved in advancing AI research through initiatives like the Nvidia AI Research Lab. This lab collaborates with leading universities and research institutions to drive innovation in AI and develop cutting-edge algorithms and models. By fostering a strong research community, Nvidia not only contributes to the advancement of AI but also establishes itself as a trusted partner for academia and industry alike.

As a result of these factors, Nvidia has become synonymous with AI, with its GPUs being widely regarded as the gold standard for AI computing. The company’s dominance in the AI market is evident from its growing market share and revenue. In 2020, Nvidia’s data center revenue, primarily driven by AI-related sales, surpassed $6.7 billion, representing a significant portion of its overall revenue.

Looking ahead, Nvidia shows no signs of slowing down in its pursuit of AI dominance. The company continues to invest in GPU technology, forge strategic partnerships, and drive innovation through research and development. With AI becoming increasingly pervasive across industries, Nvidia is well-positioned to maintain its dominant force in the field and shape the future of artificial intelligence.