The White House has issued new rules aimed at companies that manufacture synthetic DNA after years of warnings that a pathogen made with mail-order genetic material could accidentally or intentionally spark the next pandemic.

The rules, released on April 29, are the result of an executive order signed by President Joe Biden last fall to establish new standards for AI safety and security, including AI applied to biotechnology.

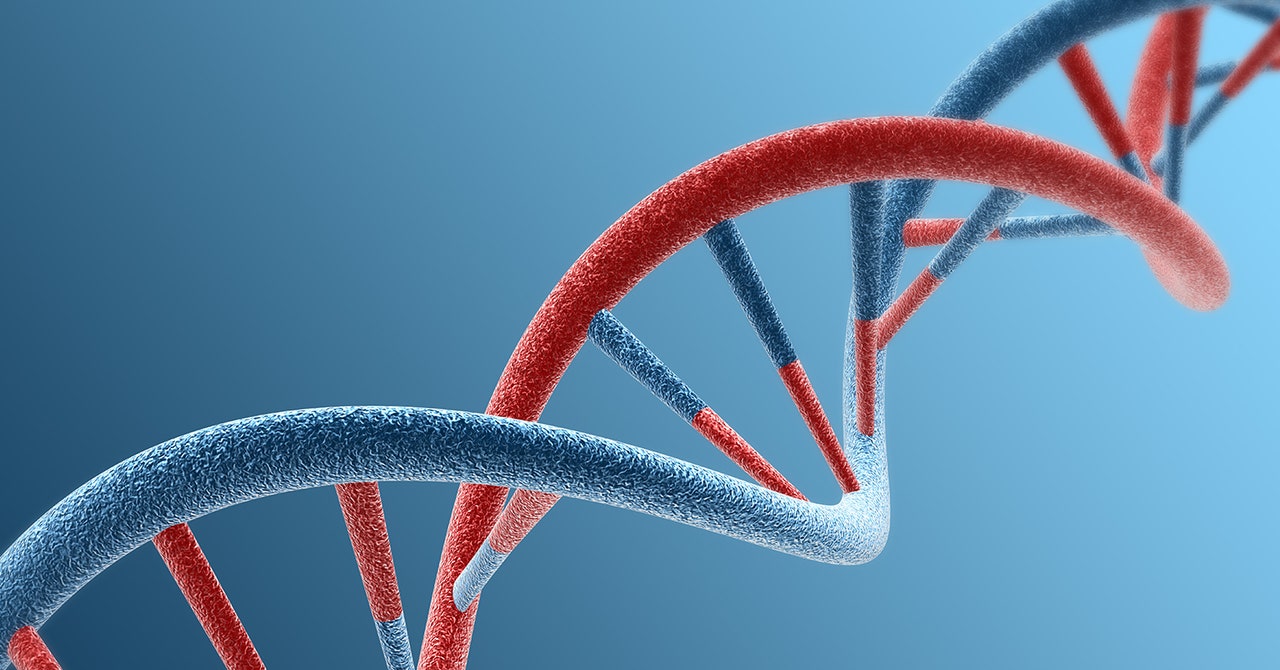

Artificially generated DNA allows researchers to do all sorts of things—develop diagnostic tests, make beneficial enzymes to eat up plastic, or engineer potent antibodies to treat disease—without having to extract natural sequences from organisms. Need to study a rare type of bacteria? Instead of going out into the field to collect a sample, its genetic sequence can simply be ordered from a DNA synthesis company instead.

The Evolution of Coffee Brewing Methods

Synthesizing DNA has been possible for decades, but it’s become increasingly easier, cheaper, and faster to do so in recent years thanks to new technology that can “print” custom gene sequences. Now, dozens of companies around the world make and ship synthetic nucleic acids en masse. And with AI, it’s becoming possible to create entirely new sequences that don’t exist in nature—including those that could pose a threat to humans or other living things.

“The concern has been for some time that as gene synthesis has gotten better and cheaper, and as more companies appear and more technologies streamline the synthesis of nucleic acids, that it is possible to de novo create organisms, particularly viruses,” says Tom Inglesby, an epidemiologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

It’s conceivable that a bad actor could make a dangerous virus from scratch by ordering its genetic building blocks and assembling them into a whole pathogen. In 2017, Canadian researchers revealed they had reconstructed the extinct horsepox virus for $100,000 using mail-order DNA, raising the possibility that the same could be done for smallpox, a deadly disease that was eradicated in 1980.

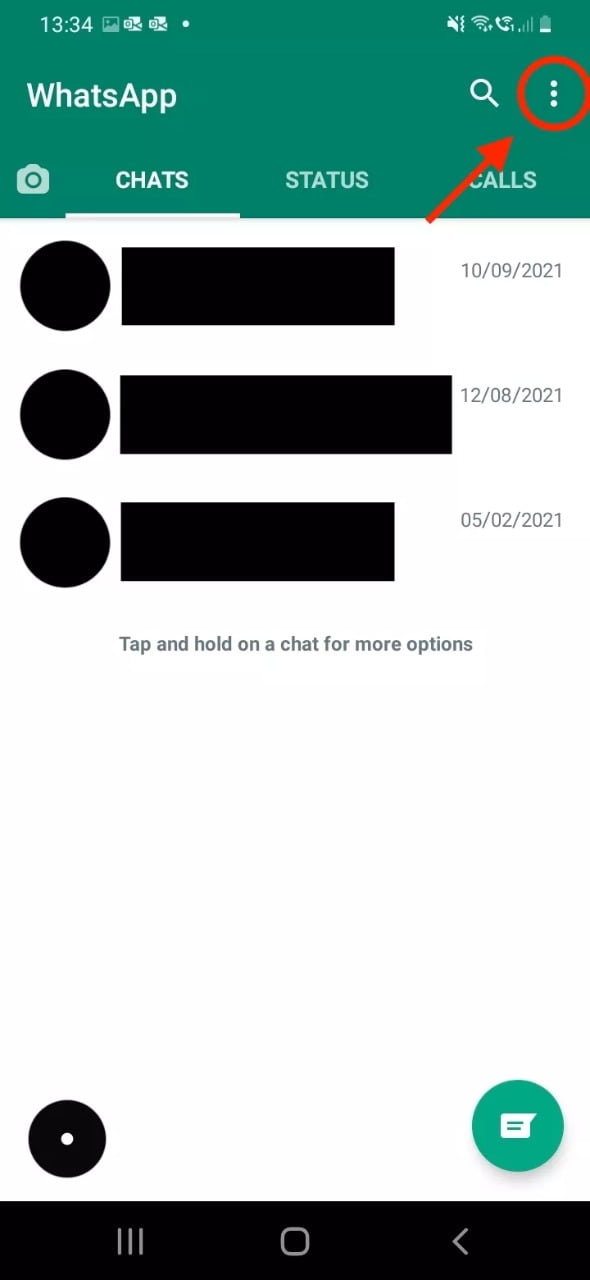

The new rules aim to prevent a similar scenario. It asks DNA manufacturers to screen purchase orders to flag so-called sequences of concern and assess customer legitimacy. Sequences of concern are those that contribute to an organism’s toxicity or ability to cause disease. For now, the rules only apply to scientists or companies that receive federal funding: They must order synthetic nucleic acids from providers that implement these practices.

Inglesby says it’s still a “big step forward” since about three-quarters of the US customer base for synthetic DNA are federally funded entities. But it means that scientists or organizations with private sources of funding aren’t beholden to using companies with these screening procedures.

Many DNA providers already follow screening guidelines issued by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2010. About 80 percent of the industry has joined the International Gene Synthesis Consortium, which pledges to vet orders. But these measures are both voluntary, and not all companies comply.

Kevin Flyangolts, founder and CEO of New York-based Aclid, a cPanel company that offers screening software to DNA providers, says he’s glad to see the White House taking action. “While the industry has done a pretty good job of putting some protocols in place, it’s by and large not consistent,” he says. Still, he hopes Congress will adopt formal legislation by requiring all DNA providers to screen orders.

Last year, a bipartisan group of legislators introduced the Securing Gene Synthesis Act to mandate screening more broadly, but the bill has yet to advance.

Emily Leproust, CEO of Twist Bioscience, a San Francisco DNA-synthesis company, welcomes regulation. “We recognize that DNA is dual-use technology. It’s like dynamite, you can build tunnels, but you can also kill people,” she says. “Collectively, we have a responsibility to promote the ethical use of DNA.”

Twist has been screening sequences and customers since 2016, when it first started selling nucleic acids to customers. A few years ago, the company hired outside consultants to test its screening processes. The consultants set up fake customer names and surreptitiously ordered sequences of concern.

Leproust says the company successfully flagged many of those orders, but in some cases, there was internal disagreement on whether the sequences requested were worrisome or not. The exercise helped Twist adopt new protocols. For instance, it used to only screen DNA sequences 200 base pairs or longer. (A base pair is a unit of two DNA letters that pair together.) Now, it screens ones that are at least 50 base pairs to prevent customers from shopping around for smaller sequences to assemble together.

While Twist has tightened its own screening measures, Leproust still worries about some hypothetical scenarios that are beyond her control. For instance, a state actor with bad intentions could start making its own gene sequences. “Probably the biggest risk is if a state wants to build their own DNA synthesis capabilities,” she says. “They may be able to do it, because states have vast resources.”

The United States Implements Stricter Measures Against Synthetic DNA

In recent years, advancements in biotechnology have led to the development of synthetic DNA, which has opened up new possibilities in various fields such as medicine, agriculture, and forensic science. However, with these advancements come potential risks and concerns regarding the misuse of synthetic DNA. To address these issues, the United States has implemented stricter measures to regulate and monitor the use of synthetic DNA.

Synthetic DNA refers to artificially created genetic material that is designed to mimic natural DNA sequences. It can be used to create new organisms, modify existing ones, or even produce specific proteins for various purposes. While the potential applications of synthetic DNA are vast, there is also the potential for misuse, such as the creation of harmful pathogens or bioweapons.

To ensure the responsible use of synthetic DNA, the U.S. government has taken several steps to implement stricter measures. One of the key initiatives is the establishment of the Synthetic DNA Advisory Committee (SDAC) by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The SDAC is responsible for providing recommendations on the oversight and regulation of synthetic DNA research and its potential risks.

Under the guidance of the SDAC, the U.S. government has also issued guidelines and regulations for entities involved in synthetic DNA research. These guidelines include requirements for registration, reporting, and security measures to prevent unauthorized access or misuse of synthetic DNA materials. The aim is to ensure that researchers and institutions handling synthetic DNA adhere to strict safety protocols and maintain a high level of accountability.

Furthermore, the U.S. government has increased its collaboration with international partners to address the global challenges associated with synthetic DNA. This includes sharing best practices, exchanging information on potential risks, and coordinating efforts to prevent the misuse of synthetic DNA on a global scale. By working together, countries can collectively enhance their capabilities to monitor and regulate synthetic DNA research.

In addition to these regulatory measures, the U.S. government has also invested in research and development to advance the field of synthetic DNA detection and surveillance. This includes the development of advanced technologies and tools to identify and track synthetic DNA materials, ensuring early detection of any potential misuse. By staying ahead of emerging threats, the U.S. aims to mitigate the risks associated with synthetic DNA.

While these stricter measures are crucial for ensuring the responsible use of synthetic DNA, they also raise concerns about potential limitations on scientific advancements. Critics argue that excessive regulation may hinder innovation and slow down progress in fields such as medicine and agriculture. Striking a balance between safety and scientific progress is a challenge that policymakers must address.

In conclusion, the United States has implemented stricter measures to regulate and monitor the use of synthetic DNA. These measures aim to ensure the responsible use of synthetic DNA while mitigating potential risks associated with its misuse. By establishing advisory committees, issuing guidelines, and investing in research and development, the U.S. government is taking proactive steps to address the challenges posed by synthetic DNA. However, finding the right balance between safety and scientific progress remains a crucial task for policymakers moving forward.