Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is flying straight to the border of space. If all goes well, the billionaire — carried in a rocket built by his spaceflight company Blue Origin and accompanied by three fellow space tourists — will join a small but growing number of people who have traveled to space but aren’t professionally trained astronauts.

Bezos’s planned trip is a big deal for Blue Origin — although its New Shepard rocket, named after the first American to visit space, Alan Shepard, has already had 15 successful test flights. Tuesday will be the first time the rocket carries humans to space. But more importantly, the journey signals that the era of civilian space tourism is officially here — or at least, it is for the very wealthy.

On July 11, Richard Branson, fellow billionaire and the founder of space tourism company Virgin Galactic, beat Bezos to the border of space when he flew there on a 90-minute trip with five other passengers on one of his company’s planes.

Bezos’s and Branson’s space travel is a reminder that space is no longer only a place where national governments set out to explore and to learn more about the universe, but a terrain that private businesses are capitalizing on. Bezos has invested billions of his own money into Blue Origin, and his company recently auctioned a ticket to space on one of its rockets for $28 million.

At a pre-launch mission briefing on Sunday, Blue Origin’s director of astronaut sales Ariane Cornell said two more flights were anticipated this year and that the company had “already built a robust pipeline of customers that are interested.” Analysts at the investment banking firm Canaccord Genuity have estimated that tourism to suborbital space could be an $8 billion industry by the end of the decade.

If you want to watch the billionaire’s departure in real time, Blue Origin is hosting a live feed on its website.

Tuesday’s flight path

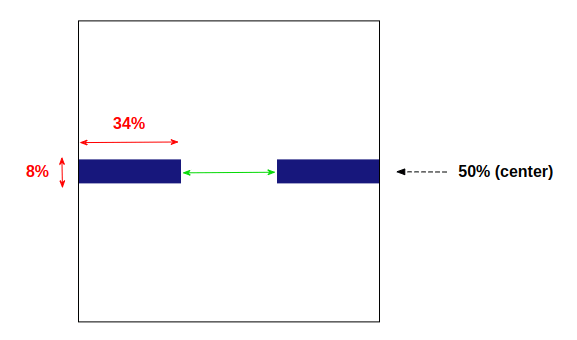

At 9 am ET on July 20, Blue Origin’s rocket is scheduled to take off from a remote desert in west Texas. At liftoff, the vehicle will launch toward space, carrying a six-seat capsule containing Bezos and the other passengers, pushed upward by a powerful, 60-foot-tall booster rocket.

To reach space, New Shepard will move incredibly quickly: faster than Mach 3, or more than three times the speed of sound. A few minutes into the flight, the capsule will separate from the booster, which will then head back toward Earth and land vertically (ensuring it’s reusable for future flights).

Meanwhile, Blue Origin’s capsule will head to the apex of its flight path and cross the Kármán line, the internationally recognized border between Earth’s atmosphere and space. That’s about 62 miles above the Earth’s surface, about 10 miles higher than Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic flight earlier this month. Like that flight, those traveling on Blue Origin’s New Shepard will also see a stunning view of Earth and have the chance to experience weightlessness.

“They’re obviously going a little bit higher, a little bit faster, but they’re still only going to have just a few minutes of low microgravity experience before coming right back down,” Wendy Whitman Cobb, a professor at the US Air Force’s School of Air and Space Studies, told Recode. ”There’s also the notion of what’s called the ‘overview effect.’ That’s when astronauts do get up into space and are high enough to see the Earth for what it is, and it sort of changes how they view things on Earth.”

After reaching the apex of the flight, the capsule will head back into Earth’s atmosphere, where it will eventually deploy parachutes to land. Overall, the whole trip is expected to clock in at just over 10 minutes.

Blue Origin’s passengers are making history

Jeff Bezos, who founded Blue Origin back in 2000, is fulfilling his lifelong dream of traveling to space. “If you see the Earth from space, it changes you. It changes your relationship with this planet, with humanity,” explained the billionaire in a video announcing the flight in June. “It’s a big deal for me.”

Bezos will be joined by his brother, firefighter and charity executive Mark Bezos. The flight will also carry both the oldest and youngest people to ever visit space: Wally Funk, an 82-year-old American aviator, and Oliver Daemen, an 18-year-old Dutch teenager. Funk, the Federal Aviation Administration’s first female flight inspector, was one of the first women to train to become a NASA astronaut, but was ultimately denied the chance to travel to space because of her gender. Daemen is joining the flight as Blue Origin’s first paying customer; he’s taking the place of a still-unnamed bidder who paid $28 million for a seat (that person reportedly had a scheduling conflict and will travel on a later flight).

While Blue Origin is making history in several ways, the flight is also a reminder that many people see space tourism, at least for the foreseeable future, as primarily funded by and for the very rich — and that it won’t do much to advance science and our understanding of space.

“The experience of a few hyper-wealthy amateurs paying $28 million to vomit for 15 minutes probably won’t bring many average people closer to spaceflight or change their impression of it,” Matthew Hersch, a historian of technology at Harvard, told Recode in an email. “Compared to NASA’s space vehicles, they are clever amusement park rides with minimal utility, intended to support a tourism business that has never been part of NASA’s charter.”

In fact, Bezos and Blue Origin are not the only private ventures looking to cash in on joy rides to space. Virgin Galactic, fresh off Branson’s flight, is already moving ahead with its plans to test and modify its planes for eventual commercial service. And this fall, SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, is sending its rocket to space too, with billionaire Jared Isaacman aboard. At the same time, NASA is also bringing these companies along for more ambitious ventures, including hiring SpaceX to transport its astronauts to the International Space Station.

“Showing customers [and] showing the world that they have enough confidence in their system to get on board and experience it themselves … is a big part of this,” Whitman Cobb, of the Air Force School, told Recode. “Part of it is also ego.”